If there had ever been any dispute about why Airbnb refuses to support simple measures that would enforce the city’s laws, we now know the answer:

A report from the American Hospitality and Lodging Association (which was covered today in the Examiner), concludes that the relatively small number of Airbnb hosts who are breaking the law in SF and other cites account for a disproportionate amount of the company’s revenue.

Multiple-unit operators – that is, people who rent out more than one place on the site — account for 40 percent of Airbnb’s revenue nationwide, the study, done by Penn State University researchers, concluded.

In San Francisco, full-time rentals – units that are never occupied by the owner but are available as hotel rooms 365 days a year – accounted for 22.4 percent of the company’s local revenue, or $43.5 million, during the 12-month period from September 2014 to September 2015.

If you add the full-time rentals in SF and the operators with two or more units – all of which are illegal under existing law – it comes to 54 percent of Airbnb’s revenue in the city.

The report shows that the company made $194 million in SF during that one-year period, and $105 million was from illegal units.

(Now: Most of the multi-unit buildings may also be full-time rentals, so there’s probably some crossover. But the report shows only 24 full-time two-unit operators and more than 1,000 two-unit hosts, so if the numbers are off, it’s not by a whole lot.)

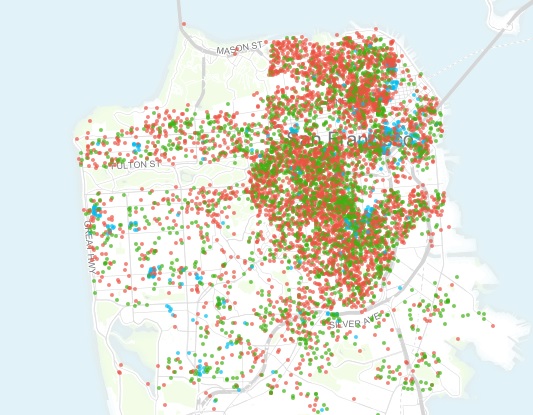

If the city simply banned Airbnb from listing units that aren’t registered, the 1,884 units that the study shows are illegally rented would be gone from the site – along with more than half the company’s revenue.

The pattern is similar in other cities. So if cities around the nation followed SF’s lead, limited rentals to the single unit a host occupies, required registration, and prevented these hosting platforms from listing illegal units, Airbnb’s $1.3 billion in annual revenue would plummet by more than half.

The company argues that most of its hosts are simply middle-class people making a little money on the side – and in terms of the numbers of hosts, that may be true. But in terms of the company’s revenue, most of it comes from what in San Francisco are illegal rentals.

And it’s interesting that the company (while it disputes the study) has taken a new tack in its PR. Here’s what spokesman Nick Pappas told the Ex:

“The overwhelming majority of Airbnb hosts are middle class people who occasionally share only the home in which they live and while Airbnb hosts keep 97 percent of the price they charge for their listings, hotels take most of the money they earn out of the community,” Papas said.

Even if the overwhelming majority of the hosts are small-time operators, the study suggests that they aren’t the ones making Airbnb most of its money. If the company had been content to be a site that connects people who want to rent out rooms, a lot of the political battles would never have happened (in large part because Airbnb listings wouldn’t be cannibalizing the city’s housing stock).

Instead, Airbnb is going for the big time, with a huge valuation and investors like Ron Conway who want to make huge returns when the company goes public. And that requires, well, allowing people (or maybe encouraging people) to break the law.

I emailed Papas to ask if he disputes the real conclusion of the study, which is that the big money is in rentals that are, at least in San Francisco, illegal.

But look at the second part of his statement. Airbnb now seems to be saying: Hey, so what if we are a de-facto hotel company. Traditional hotels are bad for the local economy and we keep the money in town.

That’s a far, far cry from the way the company has defended its actions in the past, and suggests that Airbnb is moving closer to admitting that it’s not just a tech company – and that this whole “sharing economy” thing is a lie.

The supervisors who sided with Airbnb and refused reasonable law enforcement ought to be embarrassed. The city will never be able to control its housing stock if we allow these companies to make such huge sums of money with illegal rentals.

It’s so easy to fix – but I suspect Airbnb’s not going to voluntarily give up half its revenue to do it. So I guess at some point the city has to stop asking nicely.