ALL EARS With great art comes great baggage. And quite possibly no work comes with greater baggage than Richard Wagner’s epic Ring Cycle (opening at SF Opera Tue/12 and continuing through July 1, accompanied by some lively programming). With its Lord of the Rings-inspiring premise, instant recall of rampaging Rubenesque women in Viking helmets and/or murderous Iroquois helicopters, “Kill the Wabbit” musical themes, and dark echoes of nationalism and anti-Semitism, it’s an indelible cultural touchstone.

Consisting of four full-length operas, the Ring Cycle was first produced in the period from 1848 to 1874: Wagner wrote the libretto and the music in an act of volcanic auteurism, helping to bolster the contemporary myth of the heroic genius, among other fustier notions. But with its sweeping powers and gorgeous score, this archetypal work—with its mythic quests, clashes of Teutonic titans, flashes of chthonic magic, and vivid, often weird chromatic score—continues to fascinate, drawing thousand of jet-setting Ring-lovers to minutely compare each production.

How can you put a new spin on such an idolized classic, without seeming too desperate for that illusive (and often counterproductive) quality, “relevance”?

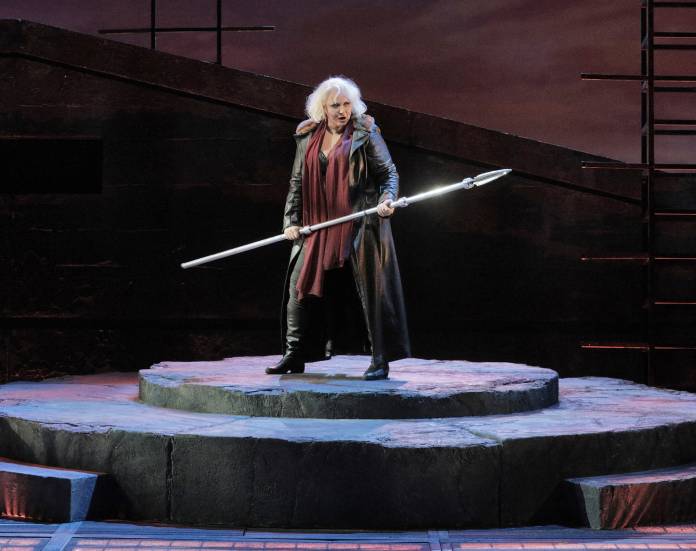

Opera director Francesca Zambello brought a revelatory Ring Cycle production to SF Opera in 2011—complete with gold-panning 49ers and corporate CEO-types. Now she’s back, updating the production with “new features, including technologically advanced projections, new imagery and restudied stage action.” But the giant gewgaws we’ve come to associate with the Ring—itself a massive special effect, in a way—pale for Zambello in comparison to the stories of the characters. Her great insight is that honing in on the personal tales of these gods and monsters will spark a fuller connection to the work, and reveal some striking parallels to our own time.

“The world scene has changed drastically in terms of politics, social issues, sex and race, Zambello said in a director’s statement titled “What Has Happened Since 2011?” “Hopefully, at some point in our lives, everything will be born anew. I am an optimist and pray for the country and the world to find its way, the same way that Brünnhilde leads us to positive change at the end of the Ring.”

Zambello elaborated on the phone to me, “For me and many of the performers, the best part of the Ring is that the gods in the story are also mortals, that they grow and change despite having this enormous stature and power, but they’re also called to account as well. You can really delve into their relationships. Wagner gave us these profound characters in the music and words, which he expressed in a sophisticated, poetic German, so it’s both exhilarating and challenging to flesh out all the meanings embedded in them.”

I asked Zambello to tell me some examples of how the characters’ growth translates into contemporary issues.

“One of the great things that comes through, and that directly applies to our #MeToo era, is that the women in this work cover an amazingly broad spectrum, and unfortunately face things we continue to face,” she said.

“For instance, Sieglinde is a demi-god who lives with a hideous mortal named Hunding, who’s like a character directly out of Deliverance. She’s famously abused, and has been forced into marriage. She ends up reuniting with her twin brother—they are two parts of the same soul—but he alone doesn’t free her. They do it together. Watching her go from this abused soul to someone in possession of herself is an amazing journey.

“Another character is Gutruna. She’s psychologically abused by her half-brother and brother. The abuse may have other dimensions as well—Wagner leaves that open. She lives in a very complicated situation. In rehearsals we talked a lot about this, about how has to adapt while accommodating her own ambitions.

“And then there’s Brünnhilde, one of the main characters, who is truly a woman of our time,” Zambello said. “She’s an amazing free spirit who transforms the world and restores the balance of nature, something even more apparent in the text now, with what we’re facing on a global scale.”

Environmentalism indeed plays into all this. “The story begins with an act of defilement toward nature—the gold for the ring being stolen from a river bed—which sets in motion so many terrifying consequences,” she said. “That sense of the loss of nature is so important in the Ring. Even more important to us, as we watch agencies like the EPA be cut in half. It’s a particularly Californian theme since here people are so conscious of that.

“We see how greed destroys the environment. The Ring is an emblem of that struggle for the natural world, and how one small action can plunge us into catastrophe.”

THE RING

Tue/12-July 1

SF Opera

Tickets and more info here.