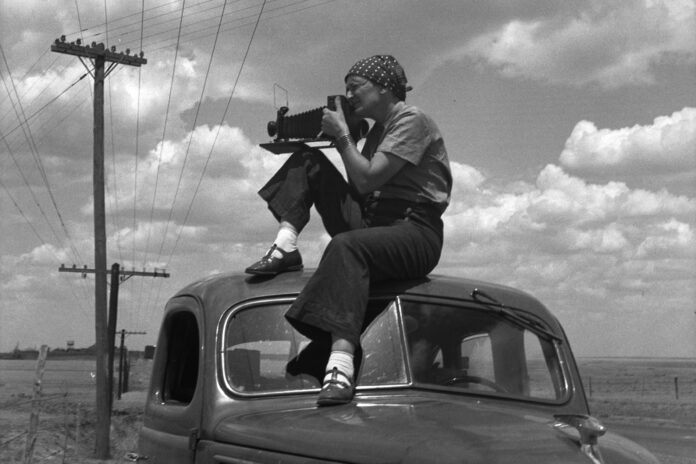

Photographer Dorothea Lange left her archives—40,000 negatives and 6,000 prints, along with memorabilia—to the Oakland Museum of California when she died in 1965, more than 50 years ago. Now, with a grant from the Henry Luce Foundation, the collection has been digitally archived.

“It’s a huge project because it’s a huge collection,” said Drew Johnson, OMCA curator. “And it’s a hugely important body of work.”

Johnson says with Lange’s work—unlike with that of her friends and contemporaries Edward Weston and Ansel Adams—it helps to see her contact sheets, since her main focus wasn’t a perfect print.

“She was much more about capturing the moment,” he said. “Her goal was not to have a fine print on the wall of the museum, and a website seemed to make sense to show that.”

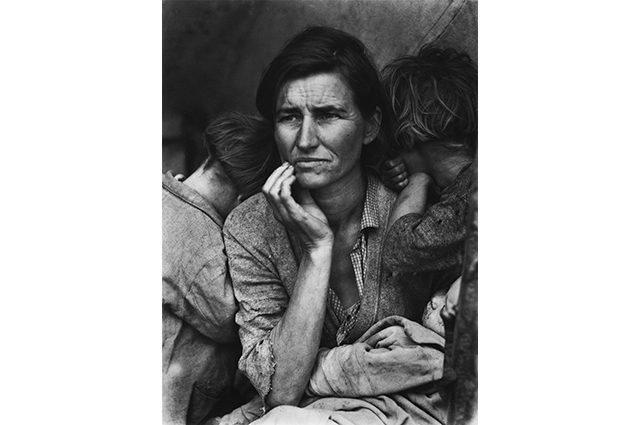

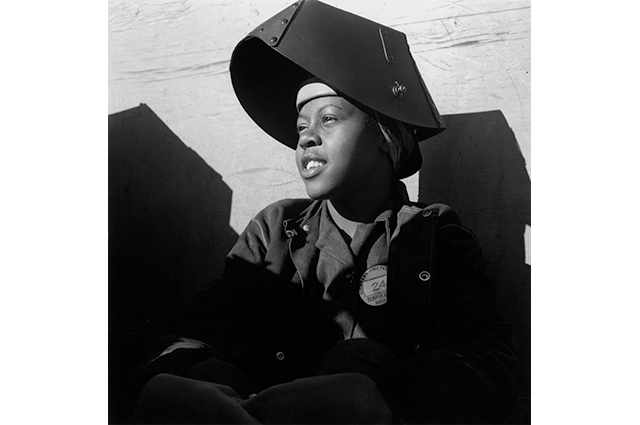

The archive is organized in four main sections. Along with Lange’s well-known photos of the Great Depression, there are photos from World War II, including her photos of Japanese Americans incarcerated in camps, post-war life in California and around the country, and her personal work, including her early portraits.

It was this studio work that made her the photographer she was, Johnson says, because it taught her how to talk with people and put them at ease.

“The reason her documentary work is so powerful, stands out, and seems personal and empathetic comes from studio,” he said. “That’s where she learned her craft and to collaborate on all these stories. Her process was not to swoop in and out in a cloud of dust. She would start chatting with people and write down verbatim a lot of their quotes, which you see on the website. She even said, ‘All my photographs are collaborations.’”

In 2017, the museum had a show from its archives that traveled internationally, “Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing“, and Johnson says her team took its cues from that show when organizing the digital archive, trying to show the activism and drive for social justice in Lange’s work.

Johnson says the museum is lucky to have such a range of Lange’s work, unlike the Library of Congress, which mostly has her photos of the Great Depression. The OMCA archives contain fairly unknown photos that stand out, such as her images of Irish county life and ship workers in Richmond, and a project she did entitled “Three Mormon Towns.” He also particularly likes a series on the Alameda County Public Defender’s office.

“The photos are so strong and it’s such an incredible local focus,” he said. “The courthouse where she did that work is literally across the street from the museum.”

Part of the reason Lange and her husband Paul Taylor, who taught economics at University of California, Berkeley, left the archive to OMCA was because it was local. Also, they liked the idea of it being available to public—not just historians and scholars.

Johnson says he gets letters all the time from people who have seen the photos and comment on them—or tell him about other images, like a shot of their grandfather speaking at a May Day rally in San Francisco that Lange captured.

Johnson has worked at the museum—and with Lange’s archive—for 30 years. He never gets tired of her work, he says, and sees it continuing to inspire people.

“It’s a privilege to work with the images every day,” he said. “It never gets old, and I discover new things. One thing I get all the time from working photographers is that they say is she’s their role model.”

The Dorothea Lange Digital Archive is available on the Oakland Museum of California’s website.