While the Marina Times (among other critics) continues to attack District Attorney Chesa Boudin for not putting enough people in jail, a new gorundbreaking study suggests that charging people with misdemeanors is likely to cause more crime, not less.

The study, by a political scientist at NYU and economists at Rutgers and Texas A&M, was published by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

The authors — NYU’s Anna Harvey, Rutgers University’s Amanda Agan, and Texas A & M’s Jennifer Doleac — looked at arrests and prosecutions in in Boston between 2004 and 2018. They concluded that people arrested for nonviolent misdemeanors who had their charges dropped were far less likely to be charged with another crime.

In fact, according to an NYU summary, the findings:

suggest that aggressively prosecuting low-level crimes could actually lead to more crime.

“Law enforcement has historically pursued punitive policies directed at these ‘quality of life’ offenses in the belief that those policies enhance public safety,” explains New York University Professor Anna Harvey, director of NYU’s Public Safety Lab and a coauthor on the paper. “But we’re now starting to learn that such policies don’t always produce more public safety. This study indicates they may make us less safe.”

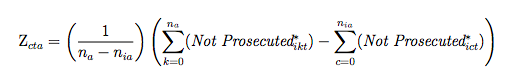

A lot of the study is technical, and it’s data-heavy. Because two of the authors are economists, there’s stuff like this:

It’s not an easy read.

And of course, there are potential problems with the data. Cases that are dropped are more likely to be less significant cases or ones that are less likely to lead to a conviction.

They addressed this by looking across the data at assistant district attorneys who have a history of dropping more charges (across the board) compared to ADAs who have a history of pressing prosecutions.

The conclusions are pretty clear:

We find that, for the marginal defendant, nonprosecution of a nonviolent misdemeanor offense leads to large reductions in the likelihood of a new criminal complaint over the next two years. These local average treatment effects are largest for first-time defendants, suggesting that averting initial entry into the criminal justice system has the greatest benefits. We also present evidence that a recent policy change in Suffolk County imposing a presumption of nonprosecution for a set of nonviolent misdemeanor offenses had similar beneficial effects: the likelihood of future criminal justice involvement fell, with no apparent increase in local crime.

This is a big deal: The study notes that more than 13 million residents of the US are charged with misdemeanors every year, and that these cases make up 80 percent of the cases in the criminal justice system.

When a first-time arrest leads to prosecution, the person is far, far more likely to be arrested again. When the charges are dropped, the person is far, far more likely to stay out of the criminal justice system.

The reasons are pretty clear. People who are arrested and held in jail or face charges tend to lose jobs, housing, and family connections. That’s particularly true in places that use cash bail.

From the study:

Cases that are not prosecuted by definition are closed on the day of arraignment. By contrast, the average time to disposition for prosecuted nonviolent misdemeanor cases in our sample is 185 days. This time spent in the criminal justice system may disrupt defendants’ work and family lives. Cases that are not prosecuted also by definition do not result in convictions, but 26% of prosecuted nonviolent misdemeanor cases in our sample result in a conviction. Criminal records of misdemeanor convictions may decrease defendants’ labor market prospects and increase their likelihoods of future prosecution and criminal record acquisition, conditional on future arrest. Finally, cases that are not prosecuted are at much lower risk of resulting in a criminal record of the complaint in the statewide criminal records system.

And so:

The results of our analysis imply that if all arraigning ADAs acted more like the most lenient ADAs in our sample when deciding which cases to prosecute, Suffolk County would likely see a reduction in criminal justice involvement for these nonviolent misdemeanor defendants. Because nonviolent misdemeanor defendants in Suffolk County are disproportionately Black, reducing the prosecution of nonviolent misdemeanor offenses would disproportionately benefit Black residents of the county.

The study didn’t look at felonies, but given the recidivism rate for people who are sent to prison, it’s entirely possible that further research might show that reducing, or even dropping, felonies in favor of alternatives like restorative justice make community more, not less, safe.

This is the approach Boudin is taking. In the short term, he’s getting hit by the news media. In the long term, his approach may be creating a safer city.

“We have a lot of work to do,” Boudin told me recently. It’s not going to be easy, but the emerging data is on the side of reform.