“Media mediates reality. Which is why it’s all illusion. Just look at AI now,” says director Camera Obscura, preparing for the return of incredible 1997 celluloid document Virtue to the big screen, with a live Q&A (Mon/5, The Roxie, SF, more info here).

The underground movie—featuring Bohemian luminaries like The Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence, Jello Biafra, Elvis Herselvis, and Doris Fish collaborators Phillip R. Ford and Miss X, plus interviews with Timothy Leary, William Gibson, R.U. Sirius and John Perry Barlow—tells a scathing tale of dystopian tech fantasy that seems all too real these days. “The story, reminiscent in tone of a Twilight Zone allegory, involves a strange woman with an odd accent who loses her husband in a graphically depicted scene of auto-erotic asphyxiation. To cope with her loss, she seeks a virtual-reality substitute (a ‘man chip’ as she calls it). This pursuit leads her into the prurient world of tech addicts who rely on ‘chip pushers.'”

Virtue is steeped in 1990s queer and alternative culture aesthetic, while establishing an early critique of the phony tech utopianism that would eventually push tens of thousands of artists and workers out of the city and destroy SF’s local economy and reputation for cutting-edge culture. Camera Obscura saw through all of this, and Virtue is proof that not all SF denizens leaped enthusiastically aboard the Web 1.0 train.

In advance of Virtue‘s screening (which features the director interviewed by SF historian and Litquake founder Jack Boulware, and a discussion include Leigh Crow (Elvis Herselvis), Phillip R. Ford, Lu Read (Fudgie Frottage), Alvin Orloff, Beth Custer, R.U. Sirius, and other foundational figures of local ’90s culture), I spoke with Camera Obscura about making the film, underground life as an artist in the 1990s, the Internet as a form of state militarism, and our harmfully addictive social media moment.

48 HILLS Can you tell me a little bit about what life was like for you at the time you made the movie? Were you a club kid, a bohemian artist, a punk, a tech utopian?

CAMERA OBSCURA Coming of age on Polk Street, straight out of high school in 1977, had the effect of permanently imprinting me with the high bacchanalia of 24-hour discos, bathhouses, and foreign films. I had no idea when I moved into the Leland Hotel that I had landed at ground zero of the gay cruising capital of the world. I just moved there because it was easy. Pay by the night, or the week, or the month. Everything seemed so easy back then. When you’d meet someone, and you’d just as soon jump into bed with them as shake their hand. The vibe was omnisexual. There was no AIDS, no COVID, and no venture capitalists. The worst thing imaginable was catching herpes.

Harvey Milk and Mayor Moscone hadn’t been shot yet. The Jonestown massacre had not yet taken place. San Francisco back then was a nonstop celebration of art, music, personal liberation and human creativity. Lots of pot smoke in the air. And rents were cheap! I sold popcorn at the Strand Theater when Mike Thomas was programming, which gave me a film education that topped anything I learned at NYU and USC. Block parties would spontaneously erupt with dancing in the streets. The gay community was at the center of it all. It was this sort of no-holds-barred joyful spontaneity that inspired me to learn how to make movies.

At the time I made Virtue, a decade had passed. I had returned to San Francisco after film school. I couldn’t wait to get back, like a salmon returning upstream to spawn. I came home to find a city traumatized by the AIDS pandemic and its endless parade of casualties. But so many people responded to the very tangible Grim Reaper with defiant joie de vivre and partying harder than ever. I think Alvin Orloff’s masterwork Disasterama! articulates that phenomenon to a tee. I spent a lot of time at the clubs and galleries, and never missed a week of Klubstitute. It was like church for me. Cartharsis! With Diet Popstitute as the High Priest. I even dedicated my film to him, as well as to Sister X-tasy Marie Collette, and also to my mom.

And in order to keep this important history alive, I have made the GLBT Historical Society part owner of the Virtue, to receive 50% of all profits in perpetuity. They are a cornerstone of the City’s culture.

48 HILLS How did you round up such a fabulous cast? Are there any tales of chasing them down to make the movie or wild times on set?

CAMERA OBSCURA Like I said, Klubstitute was like church, and all the fabulous regulars were the congregation. Rounding them up was as easy as organizing the church bake sale. The only person I had to “chase down” was Wally Sherwood, since I wasn’t into the leather scene and didn’t know its denizens. I used to see him at the Folsom Street Fair—all four feet of him—decked out in a leather cap, leather harness, and leather shorts, with his leashed six-foot-tall boyfriend carrying a six-pack of Hamm’s. Do they still make Hamm’s beer?

Anyway, Wally was pretty easy to find. I just called The Eagle and they gave me his name, which I looked up in the phone book. I still remember his number: 415-ALL-HOOD. He plays Phillip R. Ford’s romantic interest in Virtue. Phil once described kissing Wally Sherwood “like getting hit in the face by a bottle of beer.”

In retrospect, I’d say that everyone back then lived for creative expression. It’s hard to imagine that now, things are so diametrically different. People never said “no” to a creative project. I believe it had to do with the unspoken understanding of the tenuousness of life. People were living life to its fullest, living each day as if it were their last. Full-hearted creative collaboration was everywhere. And brilliance! I wanted to capture this dazzling community on film, just as much as I wished to make a statement about technology.

When I met Sister X, aka John Chidester, we would talk for hours about the meaning of the film and the significance of the scene that features the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence. She was one of the founding members of the Sisters. She and I made the conscious decision to depict the “drag queen” sisters with enormous spiritual dignity, as opposed to just painted clowns, which had never been done before in recent culture at the time.

By the time we filmed her scene, she was suffering from full-blown AIDS and was in the hospital. She actually pulled the IV out of her arm to get up from the hospital bed and make it to the set. What a trooper. You can see an otherworldly quality about her in the film. She was, indeed, on the brink of the next dimension. That ethereal quality certainly fulfilled our desire to bring a holiness to the scene. She passed not long after the filming.

As far as “wild times on the set,” I’m sure they existed, but I was too busy concentrating on filming to pay attention to anything other than lighting, f-stop, focus, and continuity. Keep in mind, much of the film was shot in 16mm film, where it’s not like today. There was no such thing as playback. You have only your own knowledge of the abstract properties of light and exposure to rely on. You can’t see what you’d shot until days later, when the dailies come back from the lab. It was always magic. There were so many tactile pleasures in real filmmaking, with celluloid. If I had known back in film school that everything would go digital, I would have chucked it all back then and become a painter.

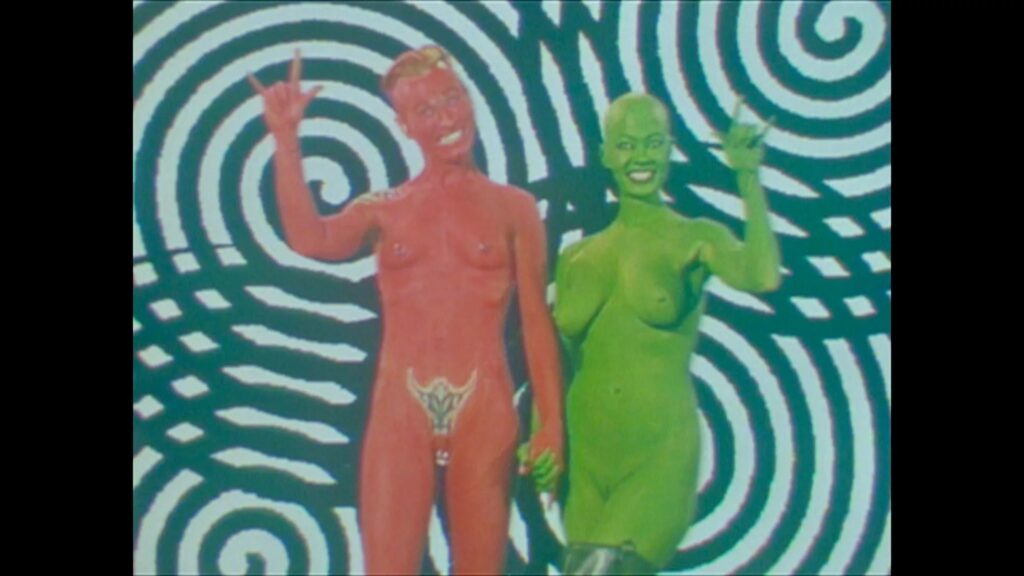

I do remember a sort of “wild times” story from Michael Angelo Albanese, who was a camera operator during the scene with Terri Gillentine and Idexa Stern playing the Modern Primitives in the Elvis Herselvis sequence. We were filming in Terri’s loft south of Market, and Michael got a kick out of the fact that we had to keep reshooting several takes because someone in the upper area of the loft had a really noisy sex toy that kept ruining our audio. The dildo sounded like an Osterizer.

48 HILLS In 1997, I feel there was still a tiny bit of remaining optimism that the growing tech world could be harnessed for human good rather than capitalist evil. How did you feel about tech then?

I always hated tech. I never believed the sales pitches that it was going to supposedly democratize the planet, or level the playing field, or empower individuals with knowledge, or whatever hogwash they were serving up. How could it? The technology was developed by the Pentagon to dominate and subjugate. Smart phones and Roombas and social media are just spin-off inventions for the consumer market. Let’s face it, it’s the coders in control. Or rather, whoever controls the coders. Bill Gates. Mark Zuckerberg. Jeff Bezos. Elon Musk. Larry Ellison. The usual suspects. And they all work for the Pentagon now. Or is it vice-versa? Whatever, the goal has never been altruistic. This technology is an instrument of hierarchy, designed by the military specifically to centralize control in a few hands.

Digital technology’s most disastrous inherent quality is that it bypasses the boundaries of time and space. This is prized in war, but it harms in so many ways. Most destructive is how digital communications, robots, and algorithms work at lightning-speed to down forests, mine, drill, and extract ever more resources all over the planet. The calculations are limitless and all-encompassing, but Earth’s resources are not. All life on Earth has been effectively subjugated and invisible-ized by the Megamachine.

And this is precisely why I made Virtue. There is a scene early on where Hundee’s husband auto-erotically asphyxiates himself. Aside from the sensationalistic nature of the scene, her response to his death is a metaphor for how this technology lures us away from dealing with the real world. Instead of dealing with the dead body beside her, she sets out on a crazy adventure in search of a computer program to replace him. Meanwhile, his body continues to decompose in her bed throughout the course of the film. She is too transfixed by the virtual world to care any longer about the natural world.

I naively believed that my kooky, raunchy, musical allegory would somehow make an impact. But back in the 1990s, before tech’s ugliness became obvious, people just took me for a Debbie Downer. They used to always say, “Oh, you shouldn’t be so fearful of technology.” I had to explain that I wasn’t fearful. I was hateful. There is a difference. Out-of-control wildfires is something I fear. Technology is something I hate. See the difference? Although, I must admit, I do fear driverless cars now, like the one that blocked firefighters from accessing a burning building in the Sunset.

But these days, people don’t assume I’m fearful anymore. They get it. And yet, for some reason, there is still a tendency to analog-shame me. They analog-shame me for not texting. Or for using a princess phone on a landline. Or for writing my appointments on a paper calendar in the kitchen. I don’t digital-shame cashiers who don’t know how to count change back into your hand anymore. That would be rude. So why is it somehow OK to analog-shame? There was a woman recently in Hawaii who followed her rental car’s GPS directions, even after it told her to drive off a pier and into the water. I don’t digital-shame her. But you gotta wonder as her car sank to the bottom of the harbor, was she another victim of technology addiction, like Hundee?

48 HILLS What were some of the inspirations for the script and for the filmmaking itself? You include interviews with Timothy Leary, William Gibson, R.U. Sirius, and John Perry Barlow. Were there other influences, or how did those figures inspire you back then?

CAMERA OBSCURA There was a defining stage in my life that was the catalyst for making Virtue. In college, I had fallen in with a crowd of PhD computer-science students. This was during the 1980s, when Reagan was president and had poured billions of dollars into SDI—the Strategic Defense Initiative, or “Star Wars,” as it was dubbed. This huge injection of money jumpstarted research in artificial intelligence, robotics, rocket science, and digital communications. It laid the groundwork for the technology that operates all our everyday devices today.

These straight white male grad students were all super smart and creative. What was odd was that they had been given a fat Pentagon stipend for their weapons research, which they spent readily on LSD and Grateful Dead concerts. They worshipped Timothy Leary and William Gibson. Even though they were designing AI and drones and other tools of totalitarianism, their trappings were full-on counterculture, as if it somehow made it all okay.

I went along with the sex, drugs and rock and roll until the moment when the abject amorality finally hit me. One of them was describing a classified project he was designing where someone would be able to remotely operate a robot tank on the other side of the world, through a video screen and keyboard at home. If someone tried to shoot at the tank, the zit-faced kid on his couch in Colorado could blast them away.

This style of weaponry is now commonplace, but when I first heard about it in the mid-1980s, I found it terrifyingly evil. It knocked the wind out of me. No amount of LSD dosing or Grateful Dead solos could soften the gut punch that I felt. I found it equally terrifying that these boys talked about parlaying the technology into consumer products they would concoct, like driverless cars and digital books and dating algorithms. And the elation they felt knowing they were playing god—with the power of “disruption”—was also scary. It became apparent that our world was on track to be fully retrofitted in subjugation to this technology and this amoral mindset.

I sought out Leary and Barlow and other futurist icons as speakers in the film to give a sense of the techno-utopian vision that was ubiquitous at the time. They provide a context that contrasts the dystopian narrative. They were all charming and accommodating, with the exception of Leary. All these interviews were shot in Fisher-Price Pixelvision, which was a cool little toy camera that shot video and audio on an audio cassette tape. The goal was to draw attention to the fact that all media is an artifact. By the same token, I used 16mm black and white film to depict the main narrative and computer-generated color graphics in the virtual reality scenes. Media mediates reality. Which is why it’s all illusion. Just look at AI now.

48 HILLS What have you been up to since Virtue? Did you remain in the city?

CAMERA OBSCURA I never thought I would leave San Francisco. I thought I would die there, but I was displaced by these tech-fuckers, like so many other dear, creative friends. It’s like a bomb dropped on the City. Everyone dispersed, as you know. But it’s not only San Francisco. This technology is not hindered by geography. Now, every city is reeling under the algorithmic yoke that ceaselessly accelerates inequity. Tech began in San Francisco, ravaged it, and now it is ravaging the rest of the country and the world.

But back to your question, after the film came out, I moved to Kauai full time. I lived there for many years, teaching media literacy to Native Hawaiians and using video for indigenous language preservation. Then the tech-fuckers followed me there, and I was displaced again, 10 years ago. So I moved, with my mom, to the Big Island. Now Marc Benioff is buying up sacred native hunting and gathering grounds near me on the Big Island, and fencing out the cultural practitioners. I’m bracing myself for what’s to come.

48 HILLS Finally, as the movie was so prophetic in its look at tech as addiction, I’m sure you have something to say about our social media moment, as well as the complete commercialization of the Internet. How are you feeling about it all now?

CAMERA OBSCURA My first clue as to the addictive qualities of the technology came in about 1994, during a brief romance with John Perry Barlow, whose brilliant analysis, “Selling Wine Without Bottles,” had captured my imagination.

He couldn’t just snuggle in bed. Every few minutes, he’d compulsively jump up to look at his laptop. In the pre-computer world, this was indescribably odd behavior. I had no idea what he could possibly be looking at. Then I saw that he was reading messages that had come in, in yellow machine font on a black screen, which was what the early internet looked like, without any color or pictures. I was astonished that he was totally unable to participate in the real moment. It was an addiction.

Flash-forward three decades. The addictive technology has reached a level of maturity. Now everyone is hooked. Social media has replaced credible investigative reporting as the primary source of information. How can democracy ever function in this deepfake landscape? And with the rapid acceleration of AI, it’s only going to get worse. As Marshall McLuhan said, “The medium is the message.” The best thing we can do is hug a friend and take a walk in the woods. Reconnect to the real. Join the community singalong at the Roxie to save the seats at the Castro Theater. Life is too fleeting to waste building relationships with machines. Feel the powerful realness of the breath and bodies of our human community! Let’s celebrate Humanity again!

VIRTUE featuring live interview with director Camera Obscura and panel discussion with ’90s underground arts icons: Mon/5, The Roxie, SF. More info here.