Timing is a funny thing.

I’d been trying to see the latest show at the Jonathan Carver Moore gallery since said show opened in January. When life finally allotted me time on an usually-sunny day in SF, I’d apparently shown up just after its eponymous owner-proprietor had spoken with his artist-in-residence, Aplerh-Doku Borlabi. Moore had also recently sold a substantial amount of work through his space at the FOG Design+Art Fair (the officially unofficial start of SF’s fine art season) and had just returned from South Africa, the former apartheid nation-turned-anti-apartheid champions.

That all had little to do with show currently on display, but it did add a unique context to the work inside this Tenderloin gallery and ongoing events in the world outside its doors.

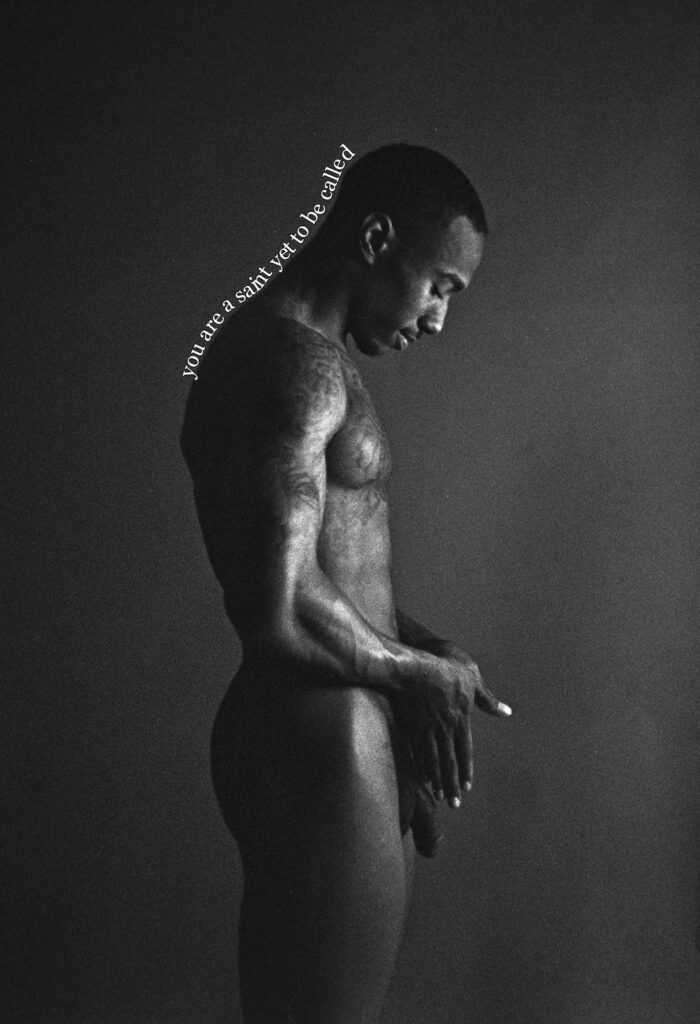

The show in question is Andrew Wilson’s Torn Asunder (through March 16 at the Jonathan Carver Moore gallery). The Daly City born and Oakland-raised Wilson—who was mentored by Carrie Mae Weems—selected the show’s photos of nude Black men from some 600-or-so photos taken during his Wesleyan days in 2013. Inspired by W.E.B Du Bois’ ground-breaking essay collection The Souls of Black Folks, the show’s monochrome photos, particularly those creating double-images, seek to look at Black men through a new light, two ways at once, really. A former nude model himself, Wilson invited other Black men to experience the freedom he’d once felt.

As Moore tells me, the openly gay Wilson encountered a significant amount of homophobia from subjects who had nevertheless agreed to be photographed. That backstory makes one take multiple looks at the double-photo Vaughn, in which the two images (one of the subject sitting relaxed, the other of him in a sort of downward-dog position) are composited in such a way that it almost resembles love-making.

Incidentally, Moore told me that the Black double identity discussed in du Bois’ text lead to many discussions between gallerist and artist, both openly queer, about how if Wilson could change anything about the work, it would be to add queerness, which was rarely-if-ever discussed openly at the time in wide-reaching texts. One looks at the double-photo Nginyu, in which the subject is simultaneously seen through front and rear profile seated on a stool, and gets the impression of someone presenting one version of himself to the world, only to carefully guard another, private face.

One of the most striking pieces is Garrison, in which the subject is shown from the side, both holding his hands behind his back (due to attentive listening or being handcuffed—you decide) and holding his hand to his face, as if succumbing to the weight of the world on his shoulders.

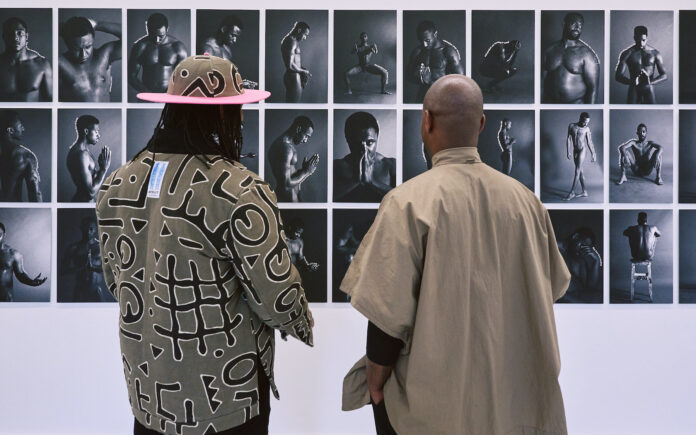

Knowing that Wilson had never previously shown the photos in public, one wonders how someone even begins to craft an exhibition out of some 600 options, let alone with a decade of passed time that possibly changes their context. The answer may lie in the show’s centerpiece, Torn Asunder. Composed of 42 images (three rows, each with 14 photos), the smaller images aren’t doubled, but rather have the text of the titular Wilson-penned poem contouring to the curves of the subjects’ bodies.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

The narrative of the poem and the careful selection of the photos tells the story of a narrator assuring a Black man that he is loved. One subject has his head down, as if ashamed; the narrator tells him “You are a saint”; the next subject then has his hands up, as if trying to push the narrator back and not accept the praise he’s been given. It’s a 42-image sequence that attempts to reverse cultural brain-washing towards a body that’s instantly regarded as a danger. Both that series and the double-images lay out Black men’s bodies stripped of pretense as much as they’re free of clothing. And given what Moore told me of Wilson recently reconnecting with his subjects over Instagram, he appears to have succeeded in granting them the freedom that nude modeling can provide.

By coincidence, I arrived home that evening to find the TV turned to Showtime. It was playing the film Kokomo City, the 2023 documentary about the lives of Black trans sex workers from Georgia up to NY. It was about halfway over, and I didn’t catch the name of the subject speaking, but she was lamenting the pressure to conform to Black body preconceptions that come from other Black folks. I believe she mentioned how both before and after transitioning, she’d never felt as much insecurity about her body from white folks as much as Black folks. We tend to internalize racism in the most destructive of ways.

That’s why the attempt at reassurance through Wilson’s work tends to linger. The poses his subjects take are never bold, so much as simply present; never exciting, so much as open for examination; never threatening, but always in danger. It says something that in 2024, we find ourselves having to fight for a body’s right to merely exist as-is. Whether Wilson successfully changes anyone’s mind remains to be seen, but the show is a welcome sight “merely existing” in Moore’s gallery.

TORN ASUNDER runs through March 16 at the Jonathan Carver Moore Gallery, SF. More info here.