Barry Jenkins was four or five years old the first time he heard about the Underground Railroad, the19th-century network that helped escaped slaves make their way to freedom in the years before emancipation. What the little boy saw in his head was an actual railroad, and he imagined men like his grandfather—a Miami longshoreman who left for work every day wearing his hard hat, tool belt, and boots—digging the tunnels and operating the trains.

Fast forward through the decades to 2016, with Jenkins’ Moonlight soon to make its world premiere at Telluride on its way to winning three Oscars, including Best Picture and an adapted screenplay award that Jenkins shared with playwright Tarell Alvin McCraney. He sat down to read Colson Whitehead’s future Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Underground Railroad while it was still in galleys and was struck by Whitehead’s description of an actual railroad, so close to his own childhood imaginings.

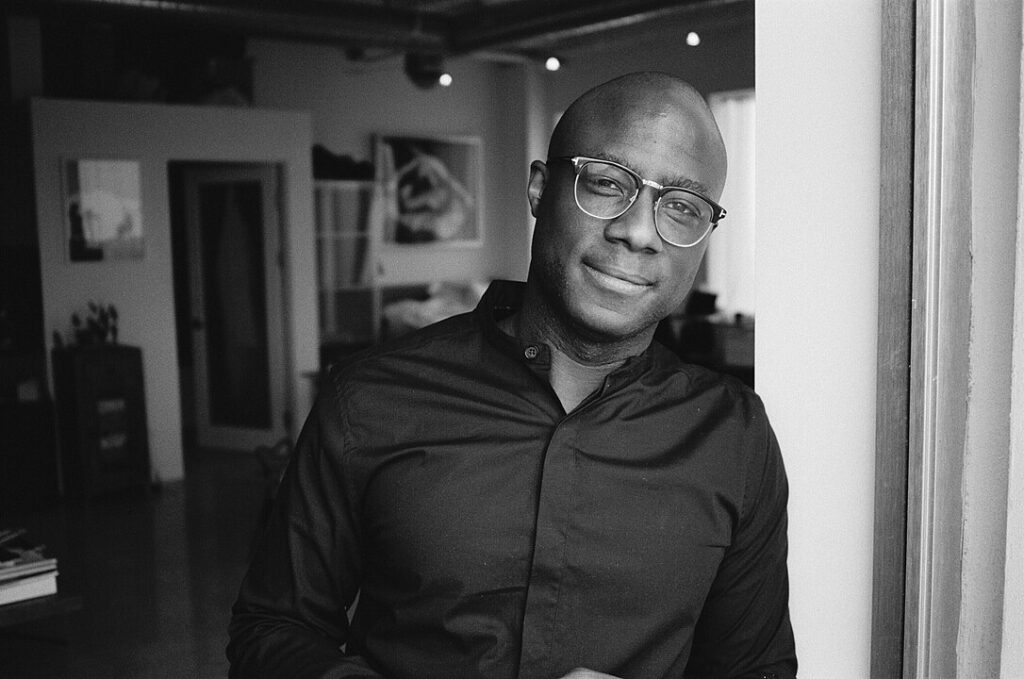

It was a story Jenkins couldn’t resist, and he adapted the novel into a 2021 BAFTA-winning and Emmy-nominated 10-part series that he will present in its entirety in five parts March 15-17 at BAMPFA with conversations to follow all screenings (more info here). He will also screen and introduce The Gaze, the experimental film he shot in parallel to the Underground Railroad production that brings the miniseries’ background artists to the forefront.

“When you’re a child, you hear something and you see it. So, to me, Black people actually built trains underground,” Jenkins says during a recent Zoom call. “That was how we took back our freedom. There’s something so pure about it, and joyous and hopeful, because it didn’t limit what the scope of what Black people were capable of. As a child the world taught me that there were certain limitations on Black folks. Black folks don’t build spaceships – because every time you see spaceships in movies, they’re piloted by white people.

“Seeing what Colton had done, it was like, ‘OK, I am going to run towards this. I am going to just run full speed towards this.’ If this was the last thing I ever made, I would be so damn satisfied and proud because it just keyed into the purest, the purest element, of who I am as a being.”

The Underground Railroad follows runaway slave Cora (Thuso Mbedo), wanted not just for her escape but for killing a 12-year-old boy in self-defense as she flees. As she journeys through several states, she sometimes finds brief respite but terror is never far behind as hostile whites are everywhere and slave catcher Ridgeway (Joel Edgerton) stalks her relentlessly.

Among the challenges Jenkins faced in mounting the production was recreating that very physical railway. The filmmaker did not want to use CGI to create the images he saw in his mind.

“I need to actually see Black people in tunnels on actual trains,” Jenkins remembers telling production designer Mark Friedberg, “How can we do this?”

It was a challenge. The railroads that control the trackways in the United States are not in the business of renting out their tracks, not to mention that the underground tunnels Jenkins envisioned don’t exist. But Friedberg found a private railway museum in Savannah, Georgia, with its own tracks that the production could use. His team built the tunnels above these tracks.

“Once we had that, then me and the cinematographer James Laxton, we just these very open conversations of what it would be like to see this thing for the first time,” Jenkins remembers. “You know how the light of it would just overwhelm, would overwhelm everything.”

The production easily could have ended in disaster. It was a complicated shoot, spread out over several states, with different casts in each one, outside of the leads. A traveling road show, Jenkins calls it. For episodes one, two, and 10, the first ones filmed, that complexity wasn’t as much of an issue. Each was carefully planned with the shots listed out. But then the production ran up against the iceberg of a budget calamity. For episodes three through nine, the production had to be nimble and Jenkins had to be quick on his feet.

“We were just making it up as we went,” Jenkins says. “And so, depending on where we were when it was happening, these different people come together and they will create a different tone. The different environments will create a different tone… What we had to rely on was the cast and the crew and how things felt because we were relying on a very organic feeling.”

Despite the budget issues, Jenkins couldn’t resist starting the project within the project that became The Gaze. Watching his large cast of background artists moving about the set in period costumes made such an impact on the director that he decided to focus on them.

“I just felt drawn to them in a way that it felt like it would be almost a crime to have them remain solely in the background. And so, we started creating these portraits of them,” Jenkins says.

The film’s images function almost like modern-day daguerreotypes glimpsing back at the past while the past glimpses back. Laxton’s cameras capture people in cotton fields, towns, train stations, and more, posing as still life while the camera moves and the world goes about its business around them.

“The Gaze didn’t come to being until maybe three weeks before the show launched,” Jenkins says. “I was sitting at home, hungover, I’ll be honest, and I put on one of these reels that one of our assistant editors just cut together. I wanted to see every single one of those portraits we did and there were about five hours worth. And I thought, ’There is a crystallized version of this that I think would be very powerful and I think adds this extra spiritual and emotional dimension to the show. And that was how it came to be.”

For Jenkins, the weekend at BAMPFA is a kind of homecoming. He lived in the Bay Area for a number of years, shot his Film Independent Spirit Award-nominated first feature Medicine for Melancholy in San Francisco, and the movie theater at BAMPFA was a favorite haunt.

“I first saw Bela Tarr’s Satantango, which is seven-and-a-half hours there,” Jenkins says. “I saw it with James Laxton with, like, a 15-minute intermission. And that was where I first saw The Decalogue and realized, ‘Oh, you can make something of this duration, and it’s a cohesive, immersive experience.’ It’s not like watching, you know, like eight seasons of Friends. It’s this very intentional cinematic experience and it always lodged in my head that it would be really interesting to do something like that.

“When I saw a movie at BAMPFA, it was gonna be the real shit. It was like the meat that sticks on your bones, you know? And so, the idea of screening this there…. We mixed this show in a movie theater, we knew it would live on television, but we always wanted it to be able to stand up, in a theatrical exhibition environment. I’m sure not everyone will be there for every program, but maybe there’s one or two people who will get the full immersion in the world of The Underground Railroad over the course of 72 hours, in the same place where I got the full immersion Bela Tarr’s Satantango. That’s incredible. That’s absolutely incredible.”

THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD w/ The Gaze plays Fri/15-Sunday/17 at BAMPFA, Berkeley. More info here.