The American photographer Irving Penn (1917-2009) once confessed, “I’ve tried a few times to depart from what I know I can do and I’ve failed. I’ve tried to work outside the studio, but it introduces too many variables that I can’t control. I’m really quite narrow, you know.”

Those of us with only a cursory knowledge of his iconic fashion photography, or his portraits, or his ethnographic studies, or his still-lifes (including a late series of monumental cigarette butts) might concur with this elegant self-deprecation, but, taken together, the work demonstrates that studio photography—and Penn constructed studios even when on location to avoid distractions—can explore reality with imagination and impact. Penn, again: ”I can get obsessed by anything if I look at it long enough. That’s the curse of being a photographer.” Studio photographs can be microcosms, or, to quote the title of Penn’s 1974 photo series, “worlds in a room.”

The nearly 200 works on display in Penn’s career retrospective at the de Young (runs through July 21) cover more than six decades of this intent, respectful looking and recording. The artist grew up in New Jersey and studied drawing, painting, graphic design, and industrial arts in high school; in college he studied with the cosmopolitan designer Alexey Brodovitch, who embraced European modernism and personal interpretation, and led his young charges on interpretive field trips to inartistic locations like factories, dumps, shopping centers, and housing projects. Brodovitch asked them—echoing the ballet impresario Diaghilev’s command to Picasso—to “astonish” him with their creativity. (His other students include Richard Avedon, Robert Frank, Garry Winogrand, and Hans Namuth.) When Brodovitch took on the job of freshening the look of Harper’s Bazaar in 1934, he featured some of Penn’s college drawings. In 1941, after a year traveling across the United States and Mexico, photographing and painting, Penn was offered a design job at Vogue, beginning his long career with that magazine and others during the great era of magazine photojournalism.

At the de Young, Penn’s work is organized into assignments for various magazines and corporate clients, and nine self-assigned photo books (as well as two books of drawings). The exhibition was created by the Metropolitan Museum Art and The Irving Penn Foundation in 2017 to cerebrate the artist’s centenary; in San Francisco, is has been modified to include a local angle, e.g., two series of photos made during the 1967 Summer of Love at a makeshift Sausalito studio: portraits of rock bands, e.g. Big Brother and the Holding Company and The Grateful Dead; biker gangs; and hippies (“Early Hippies”) for a LOOK magazine article; and “The Bath,” depicting performers from Anna Halprin’s Dancer’s Workshop of San Francisco engaged in dramatic poses that suggest unknown narratives, resembling photographic Caravaggios.

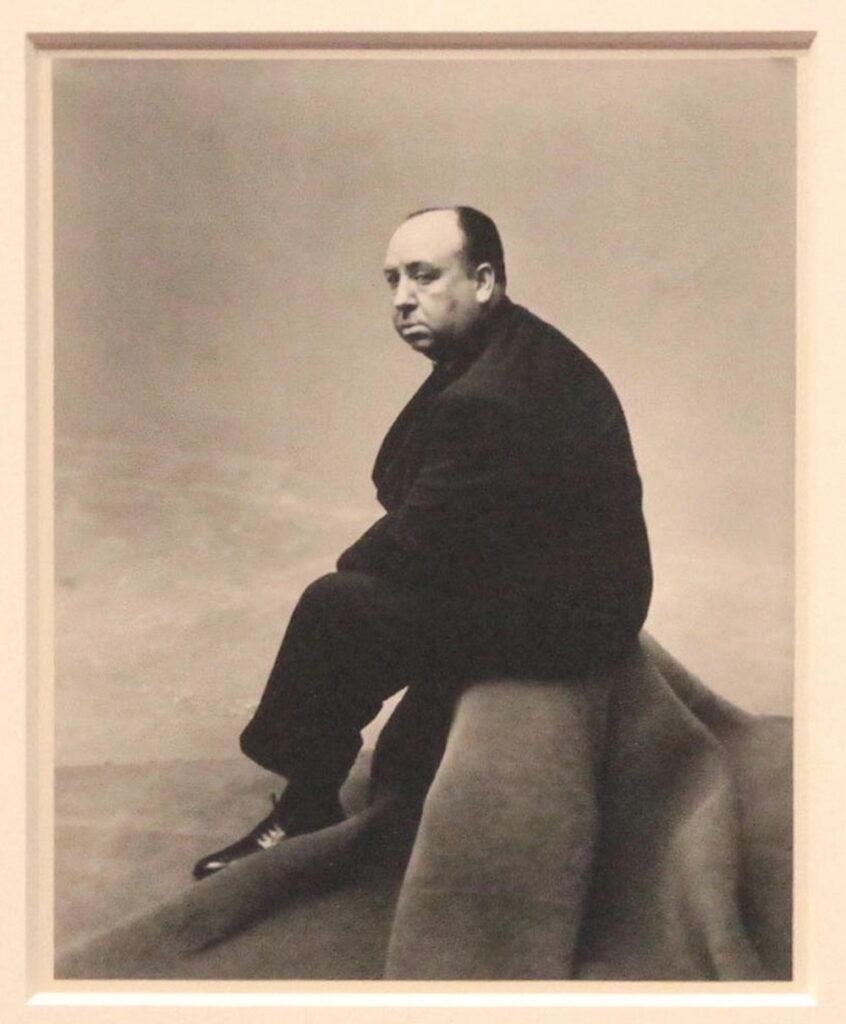

The exhibit starts with Penn’s early street photography. “Shadow of Key, Gun and Photographer,” from 1939, is a composition of shadows and signs and ambiguous space that melds Walker Evans with Metaphysical Painting; “W La Libertà (Long Live Liberty)”, from Penn’s wartime service in Italy, depicts a plaster wall with painted-over graffiti that probably once extolled Il Duce beneath a collaged headline celebrating liberation. Stylistically, it resembles the Abstract Expressionist painting that would emerge in America after the war. The Penn that is familiar to photography lovers emerges in the late 1940s in his elegant high-contrast black and white portraits of cultural celebrities set against blank or subtly textured backgrounds: a glum, gnomelike Alfred Hitchcock; an irascible Salvador Dalí without his theatrical mad-genius persona; the Surrealist filmmaker Jean Cocteau and the fashion designer Cecil Beaton, both impossibly elegant. Here too, from probably the late 1960s, is the young cellist Yo-Yo Ma, aged about 14 and already every inch the confident, consummate professional.

Penn’s fashion photos, with their stark contrasts and abstract shapes include “Cocoa-Colored Balenciaga Dress (Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn),” and “Rochas Mermaid Dress (Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn),” collaborations with his Swedish dancer wife; from 1995-’96, 40-odd years later, a couple of elegant but spooky fashion apparitions, “Christian Lacroix Duchesse Satin Dress,” with the model’s head cut off by the frame so that we concentrate on her huge puffy sleeves and bodice laces; and “Lacroix Lace Dress (Shalom Harlow),” with the model, caught in mid-stride, wearing the mantilla and peineta (shawl and headpiece) from a Goya painting, her head obscured by shadow. From 2004, an eclectically dressed mannequin in the unrecognizable “Nicole Kidman in a Chanel Couture, Karl Lagerfeld’s Mannish Tweed Jacket.”

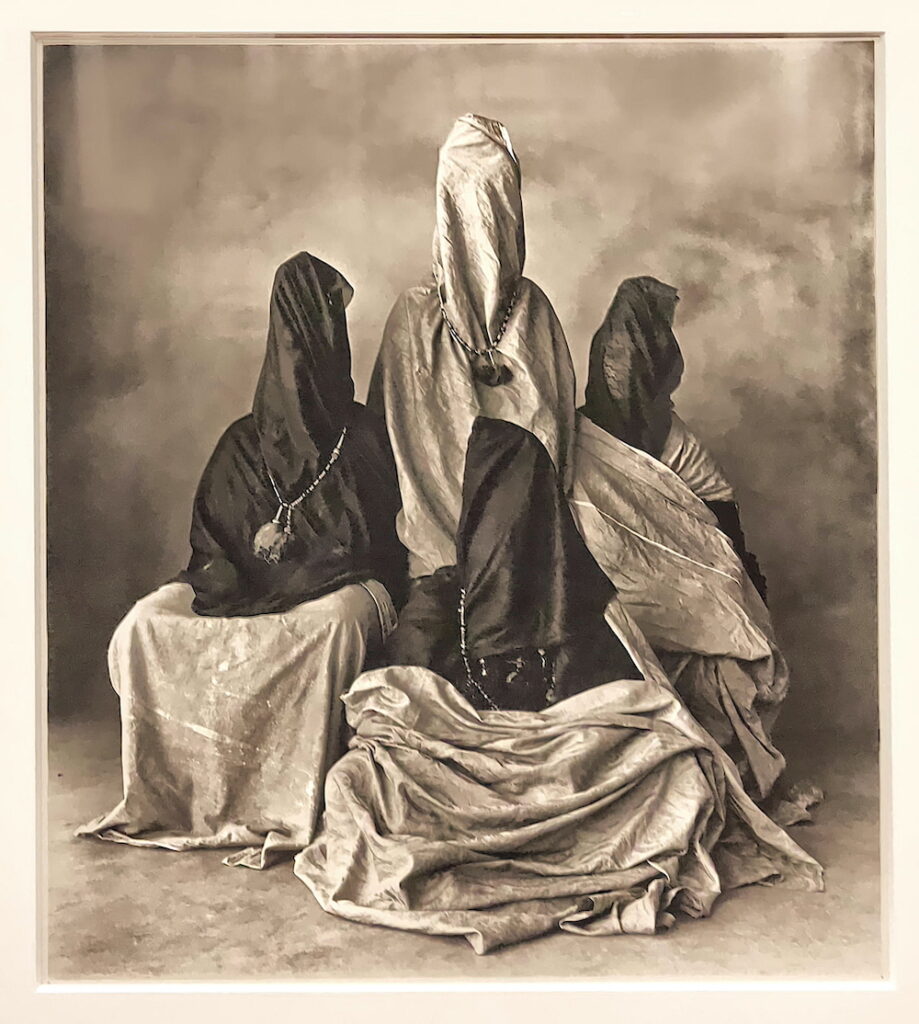

Less iconic than Penn’s fashion photos and celebrity portraits are his ethnographic studies in Peru and Africa, shot in an improvised field studio as had done for his Paris fashion shoots, and as carefully observed and composed. They have the formality and vivid presence of the best painted portraits, and neither condescend to nor exoticize his subjects. (Penn on his imagined audience: “My client is a woman in Kansas who reads Vogue. I’m trying to intrigue, stimulate, feed her. My responsibility is to the reader.”) In 1948, Penn traveled to Cuzco, and photographed his Peruvian subjects in traditional garb (“Cuzco Father and Son with Eggs”). In 1950-’51, he photographed the street vendors and laborers of New York and London in Small Trades, a body of work—its subjects a mailman, butcher, firefighter, etc.—surely influenced by the social typology portraits of the German photographer, August Sander, capturing not only the professional garb but also the pride, which was sometimes a bit larger than life, of these independent tradesmen. From 1967 to 1971, Penn traveled extensively with his portable tent studio to Papua New Guinea, Benin, and Morocco, for Worlds in a Small Room, a Vogue article and later a book (“Dahomey Children” and “Four Guedras,” Moroccan masked erotic dancers).

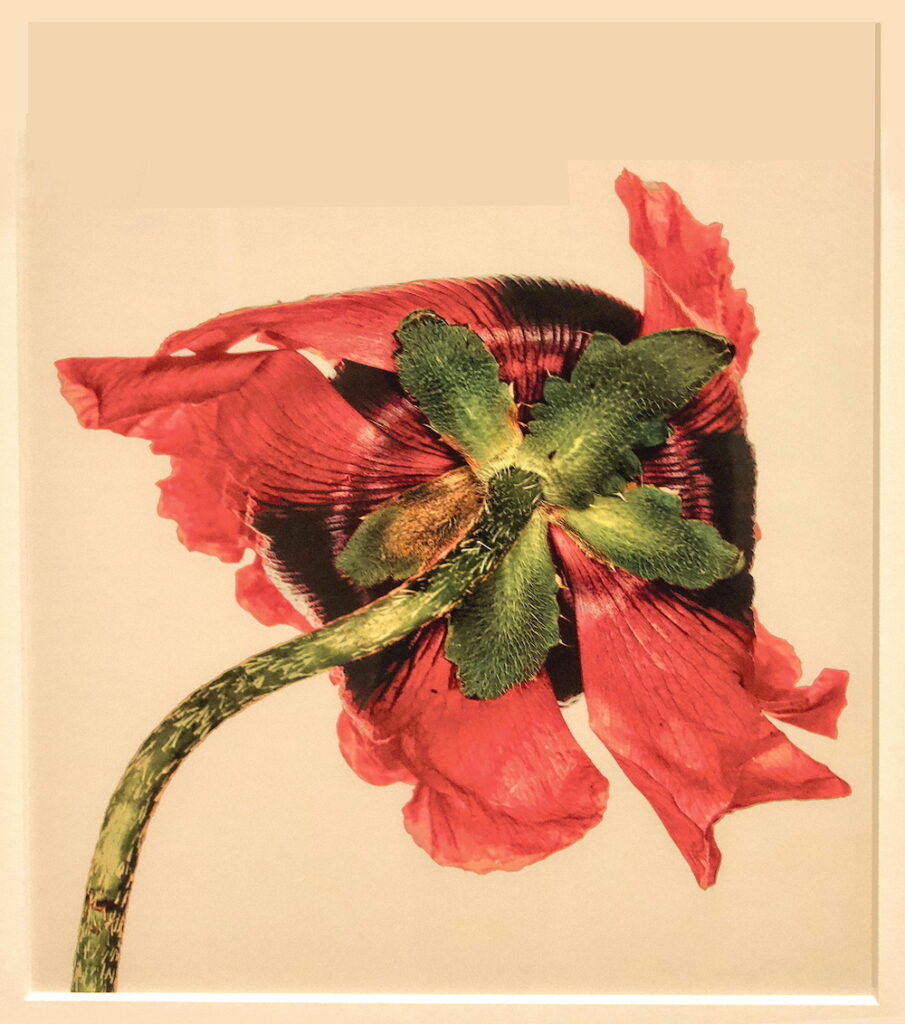

Also included are several bodies of work that lie outside the demands of commerce and were made by and for the artist alone: Nudes (1947-’50) compositions that examined the female form with an abstract, even sculptural eye, and untraditional bleaching and platinum-palladium processing (“Nude #130”); Cigarettes (1972), monumental platinum-palladium studies of gritty cigarette butts (“Cigarette No. 78”); and Street Material, Archaeology, Underfoot, and Vessels (1975-2007), focusing on unglamorous bottles, bones, rags, and garbage that verge on anthropomorphism and Surrealism (“Underfoot IX”, and the past-its-prime “Single Oriental Poppy”).

Kafka once wrote: “You do not need to leave your room. Remain sitting at your table and listen. Do not even listen, simply wait, be quiet, still and solitary. The world will freely offer itself to you to be unmasked, it has no choice, it will roll in ecstasy at your feet.” If the restlessly curious Penn did not wait in his room, his obsessive looking did reveal the ecstatic (or dignified, or humble) world rolling at our feet in the small rooms of his studios, for not only the woman in Kansas, but all of us.

IRVING PENN runs through July 21. de Young Museum, SF. Tickets and more info here.