“Too many artists are contemptuous of the public,” said Emmy Lou Packard. “Art which loses contact weakens.”

This was the defining principle of Packard, whose work is being shown at an exhibition at the Richmond Art Center. “Artist of Conscience” (a closing reception takes place on Sat/20) is a timely look at the work of the master linocut printmaker, Diego Rivera protégée, and mentor to Mission muralists.

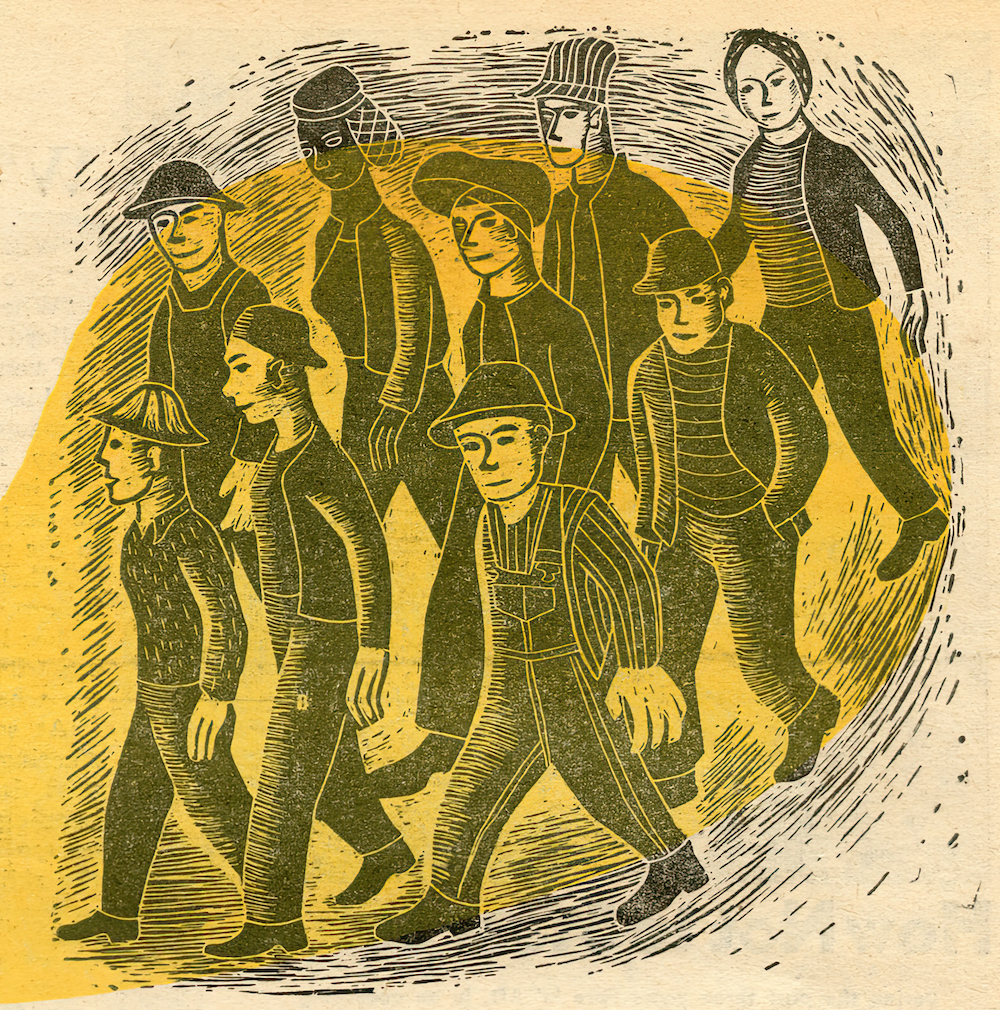

Packard was a largely-unsung San Francisco artist who painted murals throughout the Bay Area, and developed a signature print-making style of modest but highly technical mid-century linoleum prints with humanist subjects, made to be widely available to the public. Packard worked in many mediums and forms, including fresco, oils, watercolor, tile mosaic, wood block, inlaid linoleum, and bas-relief in concrete.

As a venue for the exhibition, the Richmond Art Center connects to Packard’s career at Richmond’s Kaiser shipyards, a time which she called “one of the most interesting and positive in my life in the United States.” At the shipyards, the artist worked as a draftswoman, designing transport vessels in WWII and illustrating the shipyard worker newsletter Fore ‘n’ Aft. Her illustrations for the publication promoted racial desegregation, women’s participation, and safety and dignity in the workplace.

“You could say that Packard’s art in and of itself is not explicitly political, but the fact that she made it certainly is,” says Rick Tejada-Flores, a co-curator of the current exhibition alongside visual artist Robbin Légère Henderson.

Packard’s work promoted a strong internationalist humanism. Children of all races are repeated subjects in her prints, urging the viewer against war and environmental destruction.

During her career, Packard also illustrated textbooks for San Francisco public schools, led the effort to save the Rincon Annex Post Office from Richard Nixon’s chopping block, co-founded the Artist’s Equity artist’s union, organized the annual San Francisco Arts Festival, restored the WPA murals at Coit Tower, and spearheaded a campaign that saved the Mendocino Headlands from commercial development.

“Emmy Lou Packard is absolutely a San Francisco artist,” says Tejada-Flores, a filmmaker who staffed Packard’s Mendocino gallery in the early 1960s.

In 1940, Packard served as Rivera’s principal assistant in the installation of the “Pan American Unity” mural, the largest of Rivera’s “portable” murals at 75 feet high and 22 feet wide, comprised of 10 cement panels, framed by steel. The fresco was painted by Rivera, Packard, and other assistants on Treasure Island over a four-month period and was part of “Art in Action,” a Golden Gate International Exposition program that allowed attendees to observe artists in process.

The panel, originally installed in the Diego Rivera Theater at San Francisco City College, is currently part of the large SFMOMA retrospective of Rivera’s work. The show, on display through next summer, features as its lead curator James Oles, who also knew Packard personally.

Through their shared work Packard became a close personal friend to both Rivera and Frida Kahlo, and captured their relationship in some of the most well-known photographs of the artists.

Born in Southern California, Packard spent time as a child in Mexico, where her father worked as a consultant on agricultural projects. It was there she came into contact with Rivera. Packard was a graduate of UC Berkeley, the San Francisco Art Institute, and a member (along with muralist Victor Arnautoff) of San Francisco’s Graphic Artists Workshop. The Graphic Arts Workshop was formed following the closure of the California Labor School, which “promised to analyze social, economic and political questions in light of the present world struggle against fascism,” and once had an art department as large as the San Francisco Art Institute before it was effectively shuttered by McCarthyism. At GAW, she worked on a mural series depicting a visual history of Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, and Pacific Islanders.

Packard left for Mendocino in the late 1950s and returned to San Francisco at the end of the 1960s, settling in the Mission District. Soon after her return, according to Tejada-Flores, word got around the neighborhood about a woman who had worked under Rivera. Packard’s last artistic contribution became the support and mentorship of a generation of Mission artists who would go on to found the community mural movement. She helped to provide a direct link between the artistic lineage of Rivera and contemporary Mission District muralists, resulting in the murals found on the Women’s Building and Balmy Alley, among others.

She died in the Mission District in 1998. At the time of her death, her block prints were stored at the Precita Eyes Muralists Association.

Several of the many murals in whose design Packard took part can still be viewed around the Bay Area. A mosaic piece she constructed from found objects with the help of 650 schoolchildren in 1956 is located in the courtyard of Hillcrest Elementary School in San Francisco.

Two of her murals are at the UC Berkeley campus, including a cut concrete bas-relief depicting the California landscape that adorns the facade of Chávez Student Center at Lower Sproul Hall, and another on the exterior of the student union.

Packard oversaw the creation of “Homage to Siqueiros,” a mural inside the Bank of America building at 23rd Street and Mission that was painted by Michael Rios, Jesús “Chuy” Campusano, and Luis Cortázar. Painted “for the people in the Mission who stand on the long lines in the bank on Friday afternoon,” it depicts a narrative history of the Mission District.

But as occurred throughout her lifetime, Packard has largely continued to be ignored by the art world establishment. When organizing “Artist of Conscience,” its curators found that most major museums and historical societies in the Bay Area were not interested in hosting a retrospective of her work (despite at least one institution, the Oakland Museum, already being in possession of more than 40 of her pieces.)

Perhaps this is a testament to the populist nature of her art—Packard intentionally worked in mediums that do not lend themselves to commodification. She often refused to number her prints, re-printing in different colors, sometimes for decades after the original was created.

Or maybe the reason for her relative obscurity is simply the continuing conservatism of the art world. After all, when an opportunity to host Kahlo’s first West Coast exhibition was turned down by SFMOMA, Tejada-Flores says it was Packard who worked with René Yañez and the Galería de la Raza collective to put together a show.

Ultimately, there is a certain joy in the perennial re-discovery of unknown artists like Packard. And there couldn’t be a more perfect venue for her work than the Richmond Art Center: a hidden treasure in the Bay Area, teeming with activity, free, and open to the people.

“EMMY LOU PACKARD: ARTIST OF CONSCIENCE” CLOSING RECEPTION Sat/20, noon-2pm, free. Featuring the Great Tortilla Conspiracy. Richmond Art Center. More info here.