>>We need you! Become a 48hills member today so we can keep up our incredible local news + culture coverage. Just $20 a month helps sustain us. Join us here.

In bittersweet synchronicity, fans of the Grateful Dead, were able to collectively process the passing of “Celebrity Dead Head Number One” Bill Walton, at the May 30 Dead and Co. Sphere show in Las Vegas.

That night, basketball legend Walton—who first experienced the band when he was 15 and grew to become lifelong friends with its members, seeing them perform around 1,000 times and converting many newbies to Deadheads—received a special tribute during Dead and Co.’s performance that night. During the emblematic “Fire on the Mountain,” Sphere’s immersive screen showed a virtual scrapbook filled with archival Grateful Dead memories.

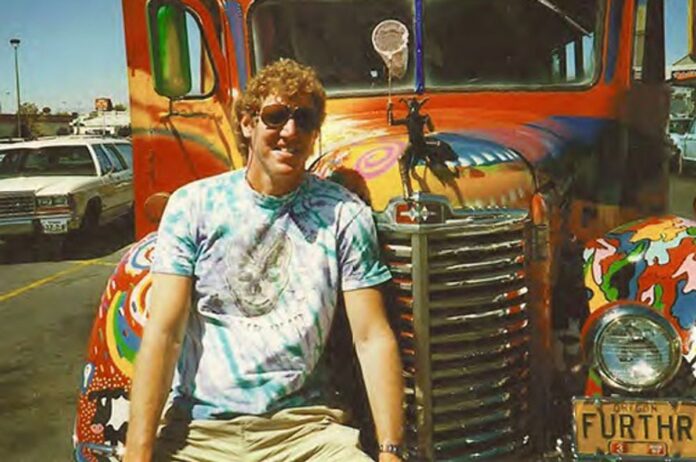

The crowd then cheered when a photo of Walton in a tie-dye Dead shirt appeared. It was one of many he’s worn on numerous occasions covering his cherished Pac-12 conference, during his career as a basketball commentator.

As Dead and Co. jammed out “Fire,” a slew of photos followed showing Walton throughout the years with members of the band, enjoying shows from the crowd, dressing in costume at Dead Co’s New Year’s Eve shows as Father Time (a tribute to the character Bill Graham used to dress up as on the same occasion).

It was a fitting tribute to the 6-foot-11 American athlete, humanitarian, and broadcaster, who became The Dead’s biggest and, more importantly, most recognized fan at shows, towering over, well, everyone.

The NBA announced his passing on Memorial Day this year: Walton, died on Monday, May 27, at the age of 71, after a long battle with cancer.

As any true Bay Arean can tell you, there are those who believe and live by that Grateful Dead aesthetic thing, and then there are those who stunt in the $400 tie dye hoodies in front of Ben & Jerry’s on Haight Street.

Not stereotyping, but c’mon now. Y’all know what it is. Yet by my math, Bill Walton lived that Deadhead philosophy his entire life.

As a college basketball player at UCLA, he followed in the footsteps of Lew Alcindor (later known as Kareem Abdul Jabbar), who won three college basketball championships.

Walton, who took over his position as a center under the guidance of the genius college basketball coach, John Wooden, went 60-0 and led the UCLA Bruins to two national titles in his first two college seasons, quickly establishing himself as possibly the second-best college athlete ever. But he was also arrested for protesting the Vietnam War.

Bill Walton won Championships with Portland Trail Blazers in 1976 and Boston Celtics in 1986, but before that, he called for resistance to the US government during a press conference in the spring of 1975.

When he appeared with his friends Jack and Micki Scott at San Francisco’s Glide Memorial Church, pastored by the late great Black minister Cecil Williams, the Scotts had just resurfaced after going underground to avoid harassment from the FBI for harboring members of the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA), including Patty Hearst, the granddaughter of newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst.

After Walton apologized to the Scotts for agreeing to be interviewed by the FBI, he called upon Americans to undertake “the practice of non-cooperation with the existing government because of the inherent evil of that government.”

Perhaps quite different from the current Deadhead concertgoers of today.

I have reliable information that the jam band community deems good arch support as part of the triptastic jams these days. Birkenstocks and Teva’s have been market-corrected; They are no longer the dominant footwear at these marathon events. Patrons have not gone dank to Dad-wear in one generational shift. They, Deadheads, are still getting it in, toking up, for sure.

But now, in this era of extended improvisations, long sets, and genre-blending music for live performances, attendees, including Deadheads and others, are wearing those bulky, weeble wobble rickety rocketry Hokas on their feet as if it were their job. Deadheads and burners alike have always made standing around, oblivious of time while wasting it, a gold medal event.

Now it’s done with comfort.

But have no fear, Dead & Co. at the Vegas Sphere shows are still bringing that melt-your-stadium face heat, averaging two sets a nite, totaling around 19 songs which works out to about the show lasting four hours. That right there proves it’s crucial to have proper footwear. Don’t nobody wanna trip balls on busted feet? (Just maybe don’t whip out that bong.)

And for that matter, Walton couldn’t. He had suffered many injuries during his career, needing 38 orthopedic surgeries, but came back to win another championship with the 1986 Boston Celtics as a role player and won the Sixth Man of the Year award on the same team that featured Boston’s best front and backcourt pound for pound.

With Danny Ainge, Dennis Johnson, Larry Bird, Kevin McHale, and Robert Parish, Walton accepted his position, did what was asked of him, and from certain accounts was an adhesive for the team. But that looseness, a bit of elasticity, and the whole communal vibe from those Dead shows was something he was eager to share with his teammates no matter what. They might not trip the light fantastic, but he was going to bring these basketball players, those professional athletes who thrive on routine, structure, and adverse pressure, outside of themselves.

“I went to my first Grateful Dead concert because of William,” mused Parish in a video. Walton arranged for that same starting team, to gain entryway, from a back door, already set up by the band, to a Dead show in ’86 at the Worcester Centrum in Massachusetts. The team sat on stage and watched the Dead do what they do.

“I was hesitant to go at first, to be honest, because I’m a jazz and R&B guy myself. But, I had a great time, I was even up shaking my little narrow butt, to be honest. I enjoyed it,” the 7-foot-inch center laughed. Celtic and basketball historians in general know it was rare for Parrish to smile about anything, in those days. Walton again, did live in service of that communal feeling.