By Tim Redmond

The campaign materials say things like “Supervisor David Campos immigrated to the U.S. from his native Guatemala at age 14 with his parents and two sisters.” It sounds pretty normal – lots of people arrive in the United States from other countries, some as teenagers. San Francisco is full of immigrants.

But statements like that always leave me a bit dissatisfied. A young man who must have been coming to terms with his sexuality, coming from a war-torn country his first year in high school to a country where he spoke not a word of the language … what was that like?

Campos doesn’t talk too much about that part of his life. But it’s a remarkable story, and while it has no direct impact on his ability to represent San Francisco in the state Assembly, it does offer some insight into his politics.

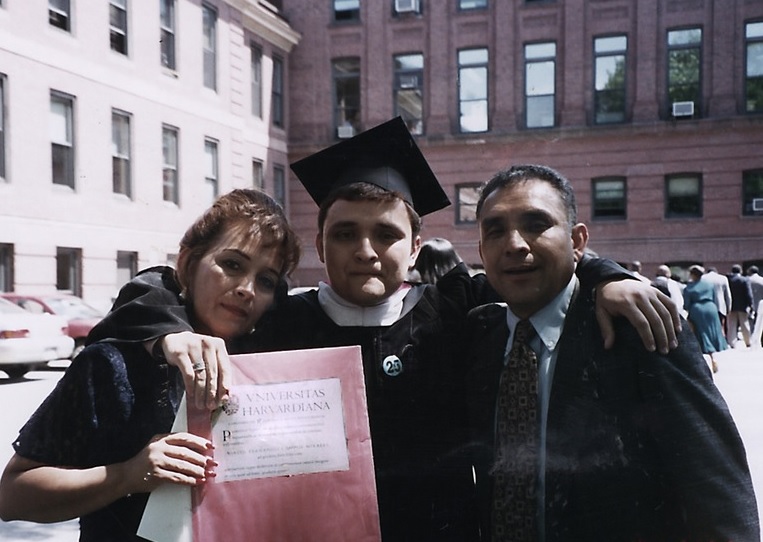

I find it fascinating how people like Campos and Sup. David Chiu, who is running against him for the 17th Assembly District seat, get to where they are. There are human stories behind every politician, and they tend to be interesting and valuable – particularly when the two contenders are, on paper, so similar. Both children of immigrants. Both graduates of Harvard Law School. Both Democrats.

So I asked the candidates to talk to me about their backgrounds and past. Chiu declined. Campos agreed to meet. The tale he told was very much a part of the experience of a lot of San Franciscans – but many of them are still in the shadows. Campos had, by his own account, exceptional luck; if a few things had gone wrong, he wouldn’t have gone to Stanford and Harvard, wouldn’t be a lawyer, wouldn’t be a politician. And those things were largely out of his control.

See, Campos came here without documents. He was one of millions of immigrants who snuck across the border and lived a life of fear, staying out of sight, worried that at any moment he and his family could be sent back to a war-torn country were there was no work for his parents and no opportunity for him.

Campos grew up in a middle-class Guatemalan family; his father was a meteorologist. But the political turmoil of the 1980s ruined the economy, put his dad out of work – and forced the family to uproot and move north.

“We tried to cross the border twice,” he told me. The first time, he was 11. The family – his dad and mom and two sisters, along with David – snuck into the country near Mexicali. “We had to hide from the Immigration Service helicopter, we called it a mosquito,” he said. “We worried about bandits. We went under the fence.

“We hid for half a day in a cemetery, hiding in open empty tombs.”

A car was supposed to take them to Los Angeles, but there were too many people in the vehicle, and it caught the attention of the police. They were caught and send to an immigration detention center.

Campos was 11. His sisters were 5 and 3. They spend a week in jail before they were put on a plane and sent back to Guatemala.

Two years later, his father decided to try to make the trip alone. He got to LA and found a job as a carpenter. In 1985, Campos, his mom and his sisters tried again.

Crossing the border into the US was just the final leg of a trip on buses and trains from Guatemala – and for much of that time, the family had to stay out of sight, since they had no papers to enter or pass through Mexico. “We crossed at Tijuana, where we had to hide for two days with nothing to eat but crackers and water,” Campos said.

When it came time to walk across the border, he took his five-year-old sister and his mom took the eight-year-old. They walked all night and crawled under the fence. “It was really cold, my sisters we so cold,” he remembered. “You could see the lights on the other side, the United States. I don’t know how my mother did it.

“You were risking your life. You saw all these empty bottles of water. You never knew if you were going to make it alive.”

When the family reached US soil, it was a feeling of relief – but just for a moment. The last trip, after all, had wound up with a stint in jail. “This time the coyotes told us to fly, to get on a plane, because nobody would suspect us,” he said. “We didn’t have any clean clothes. We didn’t speak English. I was terrified on that flight.”

His uncle met them at the Los Angeles airport, and “we were ecstatic,” he said. But then reality hit. “We were with family, but we knew that were always at risk,” he told me. “We were sleeping on the floor in someone else’s house for a month and a half before my dad found a tiny apartment. My office at City Hall is bigger than the place where my whole family lived in South Central LA.”

Campos, who had always been a good student, entered the eighth grade in one of the worst school districts in the state, and was failing. “I didn’t understand the language, I didn’t know what was going on,” he said.

After a year as an English learning student, he entered High School, excelled at everything he did, and won a scholarship to Stanford.

But there was a problem: He still had no papers. “The accepted me as an international student,” he said. “I didn’t qualify for any state or federal financial aid programs.” He survived on loans and Stanford grants – and spent his first two years living with the continued fear that he might be deported.

“I never left campus unless I was wearing a Stanford sweatshirt,” he said. “I was always worried about the police asking me what I was doing there.”

Eventually, the man who hired Campos’ father helped the family get legal status – something that probably wouldn’t happen with today’s harsh laws. He was a junior in college before he had documentation allowing him to stay in the United States and apply for citizenship.

“It makes you remember where you came from,” Campos told me. “It’s why I have this thing for the underdog.” It’s also why, he said, politics doesn’t drive him crazy: “After all I’ve been through, I don’t get fazed by a lot of things.”