Or rather, developers should show us how much they’re going to make on a project — and then we can talk about fair affordable housing and community benefits

By Tim Redmond

MARCH 19, 2015 — There’s a little-known provision of the San Francisco Sunshine ordinance — written back in the days when big developers were constantly asking the city for tax breaks, free land, or other handouts – that says those goodies have to come with a price.

Here’s the language of Section 67.32:

The city shall give no subsidy in money, tax abatements, land, or services to any private entity unless that private entity agrees in writing to provide the city with financial projections (including profit and loss figures), and annual audited financial statements for the project thereafter, for the project upon which the subsidy is based and all such projections and financial statements shall be public records that must be disclosed.

In other words, if you say you can’t make a project work without public subsidy, we want to see the numbers.

We probably could have raised the issue during the Twitter Tax Break discussions, but it would have been tricky: The mid-market tax abatement wasn’t for a specific project. And these days, what developers tend to ask for – which we (foolishly, in hindsight) didn’t put in the law – is favorable zoning.

Now what we get is demands for special height-limit exemptions, greater density, changes of use – the sorts of things that are often far more valuable than cash subsidies. I’m not a lawyer, and nobody has argued, as far as I know, that Section 67.32 ought to apply to spot zoning or other special land-use treatment (including change-of-use designations). Maybe that’s a legal case to be made.

But there’s a larger public-policy case to be made for this piece of San Francisco statute, and it comes into play with projects like the 16th and Mission development.

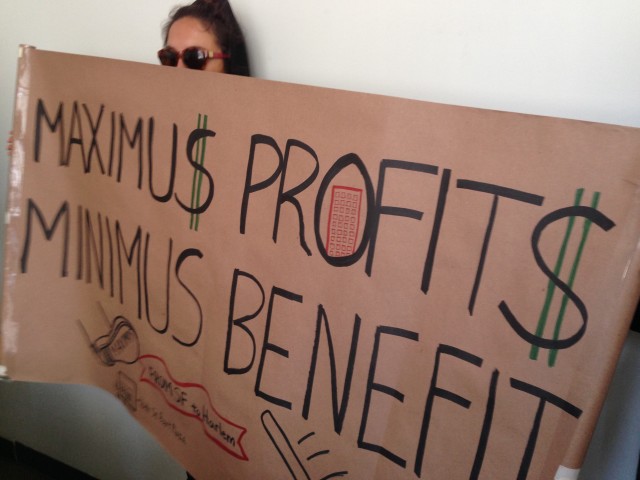

Maximus LLC, which wants to build 330 housing units next to the BART Plaza, has offered a series of community amenities – which the community has pretty resoundingly rejected.

The developer, of course, wants to turn a profit, this being a capitalist world. And Maximus representatives have made it clear that an alternative with 100 percent affordable housing doesn’t work financially.

Why not? What would it cost? What would, say, 50 percent affordable cost? What about 60 percent, which the city’s General Plan says ought to be the standard? How much has Maximus invested? What’s the expected return? At what price could the city, the San Francisco Land Trust, or a coalition of community-based housing organizations buy the land?

(This isn’t a crazy idea. In fact, it’s not crazy to suggest that the city and the CBOs start buying options on every piece of property in the Mission. An option doesn’t mean you have to buy the place; it means the owner can’t sell it without offering it to you first. Options are relatively cheap. Some places would make sense for nonprofits or the city to buy; this might be one of them.)

But again: What are the numbers? Truth is, we don’t know.

When a Maximus official was asked at the community forum to tell us about the figures – particularly, what the investors were demanding as a minimum return – he refused.

The Sunshine Ordinance doesn’t apply here. Maximus is using existing zoning, pushing a project that fits with the Eastern Neighborhoods Plan, which encourages housing near transit. I don’t think the ENP seriously considered the impact that luxury apartments would have on nearly property values, and thus on displacement, but whatever: That’s the current zoning.

But I don’t think this project is going to get approved in its current form. Sup. David Campos is pursuing a moratorium on new development in the Mission, and now that Scott Wiener has set something of a precedent for neighborhood housing controls (although he says the two approaches are totally different) there’s a good chance Campos can get six votes. That would halt the project in its tracks.

At the very least, Maximus is going to have to offer a lot more affordable housing – and every time a developer says that affordable housing doesn’t pencil out, or resists calls for community benefits, why doesn’t the city say:

Show us the numbers?

We know that high-end housing is staggeringly profitable; that’s why so much international capital is going into luxury condos in San Francisco. Let’s just take one example, offered by the Chron’s J.K. Dineen:

Millennium Partners is preparing to break ground in July on a $500 million condominium tower at Third and Mission streets, a project that could shatter records for the most expensive units ever in San Francisco.

Dineen, who knows the inside of the local real estate market as well as most real estate experts, says that the average sale will price out at more than $2,000 a square foot, meaning that the 190 condos will average $5.4 million.

I can do that math: That would mean $1.02 billion in sales.

Or: The developer invests $500 million and clears $500 million. Not a bad ROI. The city’s pension fund is trying to get above five percent in the stock market, which would make many investors happy these days. Most local businesses would die for a 15 percent profit. And building condos gets you 100 percent.

Would the project still “pencil out” if the developer had to spend another $200 million on affordable housing? Gee, I don’t know: Invest $500 and get back $800, in about 18 months? I suspect that some lenders might go for that.

But all of this is kept so secretive that the city never has the chance to ask the tough questions.

I can tell you this, from many years of watching these sorts of projects: The developer never, ever, comes to the table with a final offer. Never has anyone folded the tent and left after the city upped its demands. Which just shows how much money can be made in San Francisco real estate development.

And it shows that the city isn’t getting its share of the riches. Not even close.