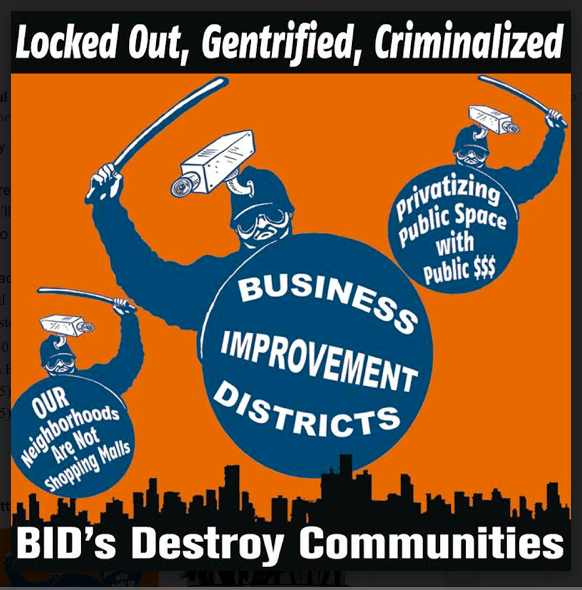

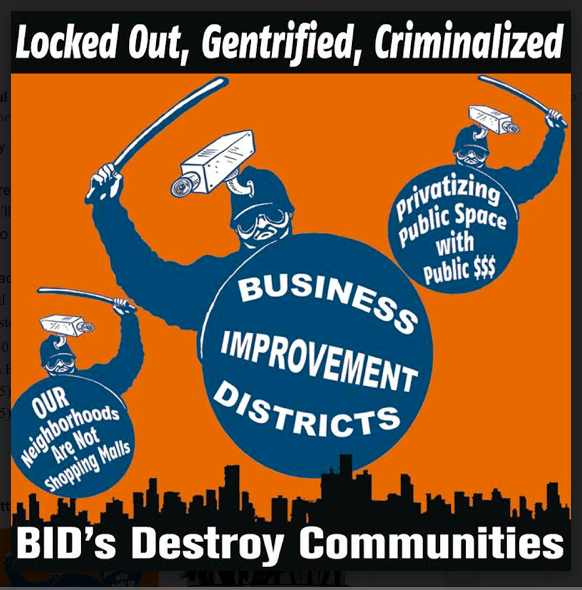

Business Improvement Districts, which are in essence private tax assessors that spend money to spiff up certain parts of town, have been using public money to advocate for laws attacking homeless people, a new UC Berkeley study has found.

The study, done by the Policy Advocacy Clinic at Berkeley Law School, examined how BIDs deal with homeless people and found a long list of problems – some involving potential violations of state law.

BIDs have become more and more popular in the past 20 years in California. Under a 1994 law, property owners in a defined district are allowed to vote to tax themselves to pay for “special” improvements that the city can’t or won’t provide.

In the early days, that meant things like new landscaping, better street lights – that sort of thing. But now these BIDs – and there 189 in 69 cities – are using money to lobby for anti-homeless laws and to pay private security guards to roust homeless people, the study concludes.

In fact, the study shows, a lot of what the BID money goes for these days is political advocacy – for anti-homeless laws. Two examples:

-

In 2010, San Francisco’s Union Square BID submitted letters of support and testified at numerous public forums for Proposition L, an anti-homeless measure to restrict sitting or lying on public sidewalks between 7 a.m. and 11 p.m. (so-called “sit-lie” laws).

-

In 2012, the CEO of the nonprofit that manages the Downtown Berkeley BID was the major individual financial contributor to the campaign for Measure S, a proposed sit-lie law.

The BIDs work through the California Downtown Association, which

actively mobilized its BID members to oppose Assembly Bill 5, the Homeless Person’s Bill of Rights and Fairness Act, and Senate Bill 608, the Homeless Right to Rest Act.

And the money they are making is used for politics:

-

San Francisco’s Union Square BID spends assessment revenue on policy advocacy under a category of services labeled “Marketing, Advocacy, Beautification and Streetscape Improvements,” and its executive director is a lobbyist registered on behalf of the BID with the City and County of San Francisco.

-

Los Angeles’ Downtown Industrial BID does not mention policy advocacy in its planning documents, yet in its quarterly reports to the city, it classifies activities like testifying at city council meetings and meeting with council staffers as assessment-funded “Economic Development and Communications” programming.

-

Assessment-funded policy advocacy expenses in the Union Square BID, the Downtown Sacramento Partnership, and Oakland’s Jack London Improvement District represent the full or partial salary costs of various personnel who engage in policy advocacy.

Business groups have every right to lobby and organize for their own interests. That’s probably not what the Legislature had in mind when it created this strange private-taxation authority, but that’s what has happened.

However, when public money is involved, it’s a very different situation. And there’s a lot of public money involved.

The BIDs (unlike the normal tax-assessment process) can hit up government agencies for money. And a lot of the money from some of these BIDs comes from the taxpayers.

This, the report says, is a problem.

The 1994 BID law permitted districts to collect assessment revenue from publicly owned properties and it increased BID spending authority. State law, however, does not authorize BIDs to spend assess- ment revenue from public parcels on all kinds of policy advocacy.151 In fact, state laws prohibit the use of public funds to support or oppose local or state candidates and ballot measures.152 Interpreting one such law, the California Supreme Court said: “A fundamental precept of this nation’s democratic electoral process is that the government may not ‘take sides’ in election contests or bestow an unfair advantage on one of several competing factions.”

In general, when BIDs use assessment revenues from publicly owned properties for policy advocacy, the public—as owners of assessed property—is being taxed to fund advocacy on behalf of businesses. We found specific instances in which BIDs or BID officials engaged in formal lobbying, support for ballot measures, and other policy advocacy.We also found examples of BIDs and their officials making financial contributions in local elections.Through the use and leveraging of assessment revenue from publicly owned properties, BIDs are spending government revenue to take sides in the democratic process.

BID use of public funds for policy advocacy may sometimes result in expenditures that local agencies themselves could not make. For example, under state law, cities and counties may spend public funds to lobby if the city or county has deemed passage or opposition of the legislation at issue to be beneficial or detrimental to the city or county.When BIDs spend assessment revenues from publicly owned properties to lobby on issues that only their managing nonprofits have identified as priorities, they bypass legal requirements designed to ensure that taxpayer funds are used to advance the public’s interests.

Then there’s the role this special districts play in enforcing laws against homelessness. The report found that many of these agencies routinely use private security forces to harass homeless people or press local law-enforcement to do that job.

The researchers found more than 2,000 pages of emails between Sacramento BID officials and the Sacramento Police Department, which included messages like this:

Sacramento BID executive asked, “Can someone swing by our building [. . .] and remove the homeless person hanging around in the corner?” Another email from a Sacramento BID to a police lieutenant asked: “When one of your officers has a chance, could s/he please ask the homeless person who is sleeping in front of

Suite C/D to leave. They are sleeping on the concrete walkway with a hacking cough . . . not very enticing for customers.”

The study found a correlation between the political activity of BIDs and the rise of anti-homeless laws – although there are clearly other factors involved.

The study also concluded that, while some BIDs try to work with social-service providers to help homeless people, the results are often not helpful.

In San Francisco, the Union Square BID attempts to move lawful (nonaggressive) panhandlers from the district.Because such panhandling is not prohibited by law, BID ambassadors are instructed first to “inform the person that their behavior is not supported by downtown businesses and actually harms the image of downtown.” If the person continues to panhandle, the ambassador is to then “stand ap- proximately 15’ away from the panhandler educating the public not to give to panhandlers, but rather agencies that can help” and will “continue this around the panhandlers [sic] area (until they move out- side of the district).”

And since most homeless people don’t trust and have had bad experiences with the BIDs, referrals and communications are worthless.

The report has a long list of policy recommendations, starting with a ban on using BID assessment revenue – particularly from public property – for anti-homeless advocacy. Cities have the ability to monitor and oversee these operations, and they need to pay more attention to an area that is largely ignored.

It’s an arcane area of law, and nobody pays much attention to it – but for the homeless population, this is a big deal.