How is the humanity of activists obscured to discredit their movement? San Francisco Art Institute explores the question in “Vanguard Revisited: Poetic Politics & Black Futures”, (opens Tue/22) a exhibit on the Black Panther Party that showcases a controversial 1968 photo series by Ruth-Marion Baruch and Pirkle Jones on the daily life of party members.

SFAI students curated a selection of Baruch and Jones’ photos to highlight contributions by unheralded party members. Guest curator Leila Weefur paired the images with the work of contemporary Black artists Kija Lucas, Tosha Stimage, 5/5 Collective, and Chris Martin to draw connections between the Panthers’ work and today’s dialogues.

The attempt to reframe discourse around the Panthers is key. In 2016, the New York Times published an analysis of media coverage of the Black Panther Party that by necessity entailed looking at how the newspaper itself had contributed to anti-Panther hysteria. Like other mainstream media outlets, the NYT was guilty of blaming the BPP for incidents that were later revealed to have been almost entirely caused by the federal government’s embedded provocateurs.

Given the media skew being perpetuated against the Panthers, Baruch and Jones’ photo series, a project of the party itself, became all the more essential.

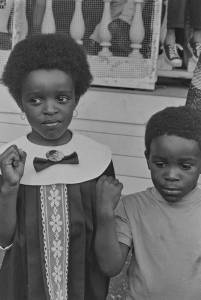

When the series was first exhibited at the de Young Museum in 1968, its contrast to mass media portrayals of the Black Panthers immediately caused controversy. Not martial enough, the public complained when they saw the images captured of the Panthers’ massively successful free breakfast program, the shots of party members watering gardens and performing other prosaic tasks necessary to keep the movement afloat. Where was all the violence?

Fifty years later, we’re once again dealing with media perceptions and misconceptions of political activists. We spoke with Weefur to learn how she and her team presented “Vanguard Revisited” for 2019 eyes.

48 HILLS Why was it important in this moment to re-exhibit Baruch and Jones’ photo series?

LEILA WEEFUR A 50 year anniversary of this particular historical moment deserves a point of cultural reflection, and an appropriate platform for comparative analysis between the old and contemporary discourses to be integrated. Baruch and Jones seemed to have recognized the importance of serving a more nuanced narrative of the Black Panthers, especially one as public facing as the 1968 photographic essay.

48 HILLS How did you interpret the students’ curation of photos? How would you characterize the focus they gave to the series?

LEILA WEEFUR Jeff Gunderson and the students were really focusing on the defining moments of the Black Panther Party that foreground the women. In an organization as infamous as the BPP, it comes as no surprise that it was mostly men who were visible, and it was important to the class to subvert that image. We were all really interested in following narratives of individuals in the BPP who were doing the invisible labor, like watering a lawn or making a grocery run. Another thing that was evidenced in Baruch and Jones’ photographs were moments of playfulness among the adults and children and the simplicity of a loving touch between two people. Those became the true defining moments.

48 HILLS How did you think audiences’ perceptions of the couple’s original work would be affected by pairing it with that of Black contemporary artists like Kija Lucas, Tosha Stimage, Chris Martin, and 5/5 Collective?

LEILA WEEFUR Our goal wasn’t wholly to affect an audience’s perceptions, because then we’d have to participate in assuming who that audience is. And making assumptions about an audience, beyond anticipating accessibility needs is dangerous. This conversation cannot exist in a vacuum of nostalgia, which is unfortunately the case for many exhibitions I have seen that look back on historical moments. The inclusion of the contemporary work is to highlight how Black artists are continuing the work of political resistance and activism, whether they identify with being activists or not. Their creative acts are as pertinent and affective as the Panther’s collective community organizing.

48 HILLS What qualities or scope were you looking for when you selected the participating artists?

LEILA WEEFUR It is impossible to capture the full scope of artists working within the lineage of creative resistance in the Bay Area in a small group show. However, these works in conversation with one another, the brutalist architecture of the gallery and the archival photographs could precipitate a discourse around Black political practices that was more nuanced than the typical grass roots organization model. As Black artists we are constantly grappling with the expectations for the works we produce to have a certain level of political visibility. My interest is in what happens when Black artists are creating work that questions that model and even more so, what happens when they are put in context with something so blatantly activistic like photos of the Panthers.

48 HILLS What are some of the things “Vanguard Revisited” says about the interaction between home life and activism?

LEILA WEEFUR What I discovered in the process of curating was the layers of tenderness and nurturement that aren’t often the focus of political movements. When you think of the BPP you don’t often consider their home and family life because it isn’t as public facing as a protest but those domestic practices are the foundation of their breakfast Program, where feeding children is the priority. Having traces of the home in 5/5 Collective’s installation “Anybody Home?” accentuates the textures and emotions of domesticity that show up in activism and resistance.

VANGUARD REVISITED: POETIC POLITICS AND BLACK FUTURES

Tue/22-April 7, free

San Francisco Art Institute

More info here.