The week before Halloween, the Roxie is reviving a series inaugurated two years ago with the seasonally-appropriate Gialloween II—a showcase for four vintage Italian thrillers from the wide-open cinematic decade of the 1970s. If you’re familiar with the type, you’ll know you’re in for a treat; if not, the trick will be on you.

Though they were largely dismissed as trashy potboilers at the time, the cinematic genre that came to be termed giallo (after the yellow covers of similarly themed Italian pulp paperbacks) is now cultishly adored by horror fans for its frequent high style and narrative idiosyncracies—as well as its generous helpings of sex and violence. So much so that the form has even inspired slavish feature-length tributes in recent years, including The Strange Colour of Your Body’s Tears, Berberian Sound Studio, Amer, and The Duke of Burgundy. They ape everything about those old films, from their visual tropes (voyeuristic POVs, talismanic details like keys and gloved hands) and groovy soundtracks to the often senseless plots, as well as the disembodied effect of actors from various nations dubbed by other actors in post-production.

Giallos were a significant element in pushing the boundaries of celluloid content in the 1960s and early 70s, when long-standing strict censorship rules against nudity, brutality and “adult themes” began to spring leaks, then collapse entirely in many nations. No wonder these films were largely dismissed in their heyday—critics and other cultural watchdogs were still assuming the stance of shocked moralists, appalled that their hitherto relatively-pure silver screen had suddenly been flooded with graphic sensationalism.

Hence giallos garnered little respect, even less so because so many were released in heavily cut, barely-coherent form when sold to overseas territories. It required the jaded distance of retrospect to see that at least some of these disreputable films had been eccentric and even artful within their genre limitations.

Not that audiences cared much: These movies were popular for reasons that didn’t have much to do with Art. They could be counted on to provide a sizable basic quota of T&A and sadistic violence. Italian exploitation cinema in its different forms (spaghetti westerns, sword & sandal flicks, et al.) has almost always been aimed near-exclusively at male viewers of, er, unrefined tastes, and the gialli personified that demo-targeting no less than if they had been straight-up porn. Yet because they were still within the spectrum of mainstream cinema, they could afford (at least until the reduced budgets of the genre’s declining years) a certain degree of posh style, as well as creative imagination.

The genre’s first major example was Mario Bava’s 1964 Blood and Black Lace, a sumptuous color thriller about murders at an upscale fashion-design house. Though not an immediate success, it nonetheless provided the template for films over the next two decades, until Friday the 13th-style slashers and occult gorefests basically killed the giallooff. That blueprint included top-billed familiar faces of faded marquee value (American Cameron Mitchell, Hungarian Eva Bartok), a lot of pretty younger relative-unknowns to play terrorized victims, glamorous European settings, and a killer whose identity is kept hidden until a resolution that’s often arbitrary to the point of WTF-edness.

This second Roxie giallo showcase brings four features from the form’s early 1970s peak, when its international popularity translated into good production values, starry multinational casts, and the launching of some talented directors who went on to long careers. Lucio Fulci (later known for such gore-horror classics as Zombie and The House by the Cemetery) indulged the genre’s surreal and softcore sides with 1971’s A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin. Florinda Bolkan plays an insomniac living a staid bourgeoise life next to another woman (Anita Strindberg) who throws psychedelic orgies every night—parties that come to an abrupt end when that woman is found murdered. With its striking dream sequences and Ennio Morricone score, Lizard personifies some of giallos’ most beloved qualities. On the other hand, its convoluted plot and turgid detectives-interviewing-

Another horror great, Dario Argento, was in the middle of his own giallo period (before 1977’s Suspiria turned him largely towards supernatural horror) when he made the likewise Morricone-scored ’71 The Cat O’ Nine Tails. Blind man Karl Malden and journalist James Franciscus are among those investigating a murder spree involving industrial espionage. It was reportedly Argento’s least-favorite film, and you can see why—it’s undistinguished by comparison to the similar exercises he made immediately before (The Bird With the Crystal Plumage) and afterward (Four Flies on Grey Velvet). Still, it’s got some dynamic intercutting, and is notable as perhaps the least likely movie to end with someone yelling “Cookie! Cookie!” (though that does make sense in context).

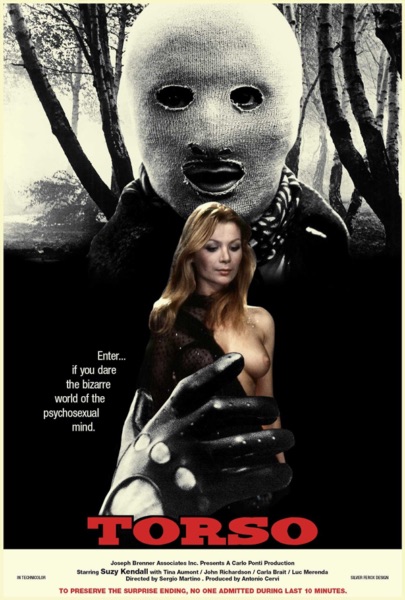

Two years later critics held their noses and audiences smacked their lips at Torso, whose memorably nasty original Italian-language title translates as “The Bodies Show Signs of Carnal Violence.” Versatile exploitation specialist Sergio Martino doesn’t rise here to the heights of giallo style he’d already scaled in movies like All the Colors of the Dark and Your Vice is a Locked Room and Only I Have the Key (another great title). But he certainly does provide a prime demonstration of the genre’s penchant towards undressing, then slaughtering, sexually available young women. This tale of a masked murderer targeting comely college students in Rome is a rather crude guilty pleasure until it reaches its long, suspenseful climax, with broken-ankled Suzy Kendall trying to elude a killer in a house already littered with the friends he’d killed while she was asleep.

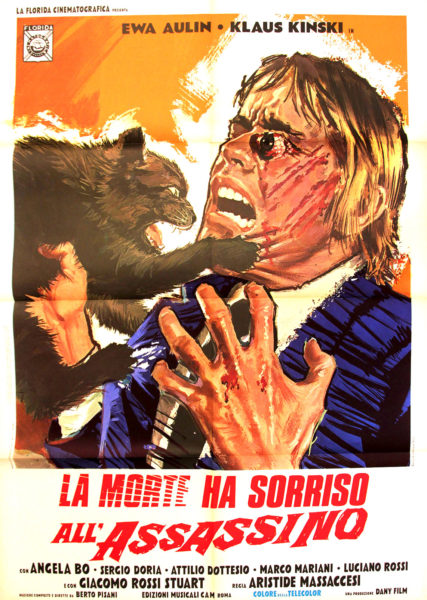

Released the same year was the most out-there of this quartet, Death Smiles on a Murderer, one of very few films directed by notoriously prolific sleaze (and later porn) maestro “Joe D’Amato” under his real name of Aristide Massacessi. It’s a creepily beautiful Gothic nightmare-poem in which Candy’s Ewa Aulin is a dead 19th-century aristocrat obsessed over by her incestuous hunchbacked brother (Luciano Rossi), imperious ex-lover (Giacomo Rossi Stewart) and a perverse doctor (none other than Klaus Kinski). Where most gialli were glorified murder mysteries, this morbid Poe-inspired fantasy dives into supernatural terrain, with our heroine returning from the grave to wreak vengeance on the living. While later D’Amato joints such as Absurd, Porno Holocaust and Emanuelle Around the World have their defenders, it’s safe to say he never made anything this luxuriantly odd again.

Gialloween II

Wed/22-Fri/25

Roxie Theater, SF.

Tickets and more info here.