On February 15, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art opened An American Project, a retrospective, of the work of multi-award-winning photographer and teacher Dawoud Bey. The show was supposed to run through May 25, before traveling to other museums, including the co-organizer of the show, New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art. But due to the COVID- 19 pandemic, the SFMOMA and other museums, closed temporarily in March. Recently the museum put up a short video of Bey talking about visualizing history, and he took over the museum’s Instagram account the week of March 30.

Bey came out to San Francisco for An American Project, and at a preview had a conversation with Corey Keller, (who curated the show along with the Whitney’s Elisabeth Sherman), in which he talked about going to see protests of the widely criticized 1969 exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harlem on My Mind, which mostly excluded African American artists. There was no protest that day, and Bey ended up going into the show, which made him think seriously about being a photographer.

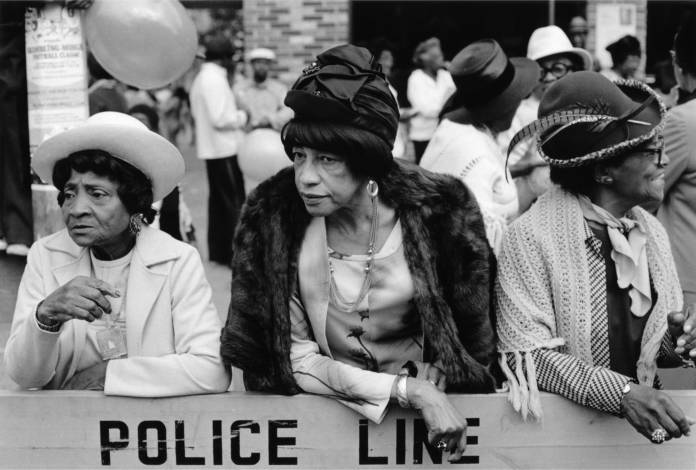

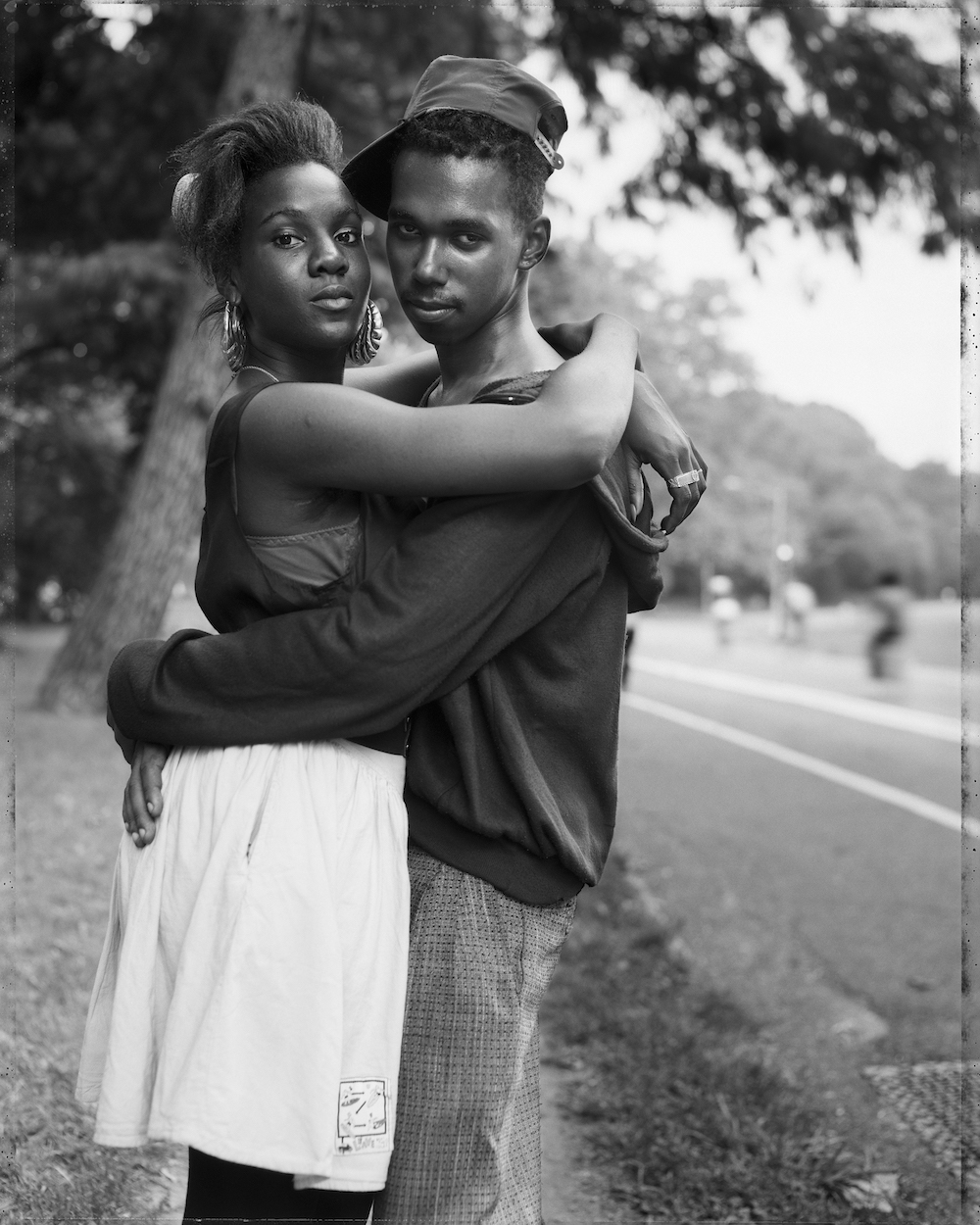

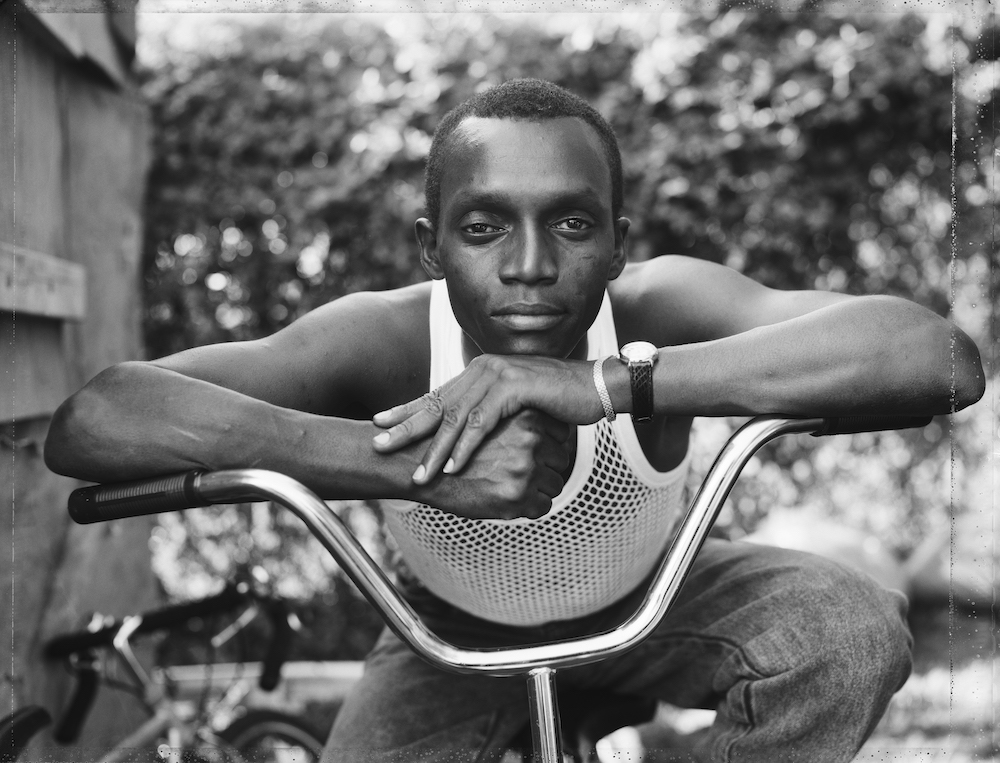

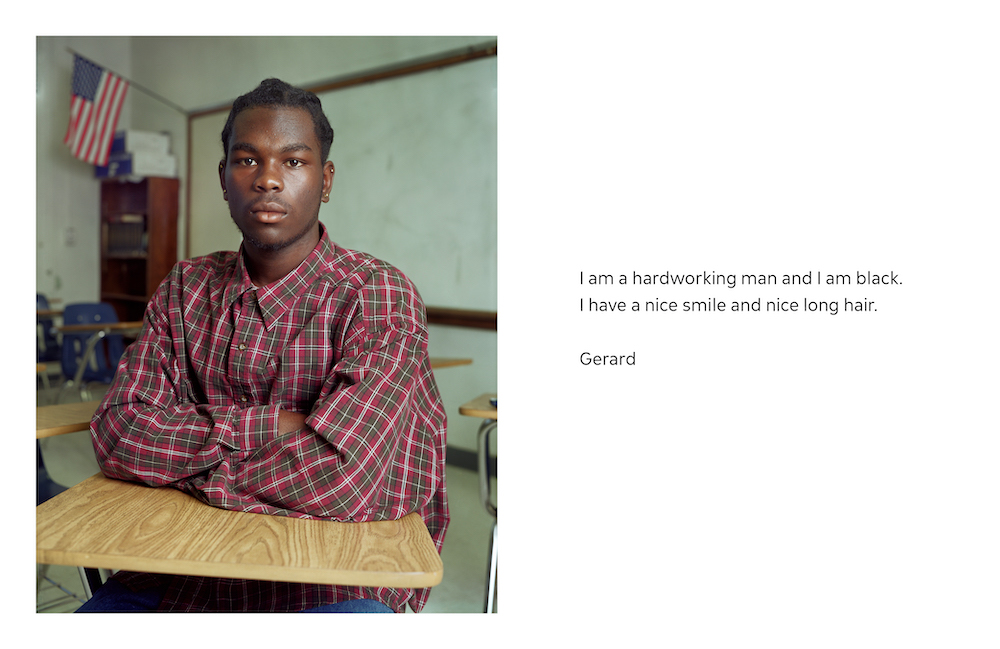

An American Project includes Bey’s first show, Harlem USA, along with The Birmingham Project, commemorating the 1963 dynamiting of the 16th Street Baptist Church in that city which killed four girls; Night Coming Tenderly, Black about the Underground Railroad; and Class Pictures, portraits of high school students accompanied by their words.

Bey sat down with 48 Hills and talked about changing from wanting his photos to show people in a “positive light” to just making honest photos; how for The Birmingham Project, photographing children the age of the ones who were killed makes history more specific; and the way the darkness and positioning of the photographs in Night Coming Tenderly, Black pull viewers into the experience of being on the Underground Railroad and running for their lives.

48 HILLS Your godmother gave you a camera when you were 15. When did you start using it?

DAWOUD BEY When I got the camera, and it was a very basic Argus C3 Rangefinder camera, I had no idea how to use it. I was more fascinated by the camera itself—the fact that the lens came off, and I began to figure out when you turn this dial the shutter would open slowly. I had no background in photography, and I didn’t any think of it in terms of what would my subject matter be. So I just started walking around with this camera. I never made any memorable photos with that camera, but I did start to notice photography magazines like, “Oh, there’s actually magazines about this stuff.” So it got me engaged with photography, and I started looking at photography books and magazines, and then the possibilities of what one might do with a camera opened up.

I guess the pivotal thing that happened was the following year when I was 16 and I went to see Harlem on my Mind at the Met. I actually took the camera with me, and I did take a picture of the banner in front of the Met. It was seeing that exhibition that began to expand for me considerably the notion of what the subject of photographs might be. Even though Harlem on My Mind was not an art exhibition, clearly the photographs were not that ones I saw in everyday newspapers and magazine, which up to that point was my only frame of reference for what photographs were. Seeing that exhibition and thinking about my family’s history in Harlem, because my mother and father met in Harlem, and beginning to realize one has to have a kind of nominal subject around which to wrap their picture making, that allowed me to begin making photographs.

48H So that led to your first show, Harlem USA.

DB Yes. They were photographs of everyday people in Harlem in the public and semi public spaces of Harlem, largely in the streets, and a few in churches and in barber shops and greasy spoon luncheonette restaurants. Those were very much in the tradition of other pictures I had been looking at—a lot from photographers of the WPA and Farm Security Administrator. Walker Evans became an early influence and Roy DeCarava. I started looking at the lot of photographs, trying to get a sense of how photos are made and what good photographs look like.

48H With that show, Harlem USA, what kind of photos did you want to make?

DB When I started out, I guess I wanted to make photographs that in some significant way contested the stereotypical notions of Black urban communities like Harlem, which are often described through a lens of some form of social pathology. So when I started out, I probably would have said I wanted to make photographs that represented the people of Harlem in a more positive light. But as I continued on, I couldn’t quite figure out what a positive light looks like. This was merely people in the act of living their lives.

I eventually came to this notion of wanting to make an honest representation of everyday people in Harlem. It allowed me to let me let go of this binary notion of positive and negative, and just try and describe clearly the people in front of me without trying to put them in a box. Just allow them space to breathe, and I realized that was enough.

48H You have talked about showing your work in the communities where you took the photos and how the act of being seen is political.

DB I thought it was very important that the work I was making in that community be shown in that community—that the people who were the subjects of the work would have access to the work. Certainly a number of these photographs are made in places very different from where they’re shown, but they’re first shown where they were made, from my first show at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 1979. It gave me a very clear and intentional way of thinking about the institution as a place of display. Not just the end point for the work, but to use the space of the museum to set up a series of particular relationships: between the museum and the community in which it sits, and trying to use the work in a way that a piece of community is in the work. It creates a different relationship between museum and the community, where they are aware they’re being exhibited in this space, which makes them more likely to want to have access to that space.

I think it changes the dynamics. Certainly at the Studio Museum in Harlem, it’s a very different set of circumstances because that place is set up in order to have a place for art objects within the African American community. I wanted my photographs in Harlem to extend that conversation. Usually the first showing of the work is in the place in which the work is made. The Birmingham Project was first shown in Birmingham because it has a very particular relationship with that history. The Class Pictures project was made in several different communities around the country, but each piece first shown in the city in which it was made.

48H Why did you decide to have the students you photographed in Class Pictures write something to go along with their portraits?

I thought it was necessary because I wanted a very dimensional representation of those young people. I’m always acutely aware of the limitation of photographs because photographs don’t do a lot more than they do. They’re mute visual objects that present a particular piece of information. But all the information that lies out of the frame, which is a lot of information, tends not to be what the work is about.

In terms of making a contemporary portrait of young people in America, I thought it was important they not only be visualized in my photographs, but that they have a place of self representation and talk about their own lives in a way that the photograph is not capable of. That the two things—my portrait of them and the text—could add up to something more than either alone can represent. In that project I though it was really important to give them a literal voice in the construction of the image.

48H You talked about your work having a through line? What is it?

DB A sense of history and place. There’s always been a kind of close looking at a place. Photographs become history the moment that they’re made. They begin to recede into the past as soon as they are made. It’s about bringing all of that into the conversation through my work. To have them become a part of the conversation from which they’ve been largely excluded.

48H You said you went to Birmingham for years getting to know the city before deciding what you wanted to photograph to commemorate the bombing the 16th Street Baptist Church by white supremacists. How did you decide on young people the same age as the children who were killed in a diptych with someone who would have been their age if they lived?

DB I didn’t want to just photograph young people in Birmingham—I wanted them to be those specific ages. The girls were 11 and 14, and the two boys killed that afternoon were 13 and 16. I wanted them to be that age because for me, the work resonated more deeply in terms of what does an 11-year-old Black girl look like, because one of the girls who was killed in the dynamiting of the church was 11. Not just what does a young girl look like, but what does an 11-year-old African American girl look like.

It’s a way of making that history less mythic and more specific. History as time passes tends to become very gauzy. “The four little girls”…. It almost sounds like a girls’ singing group. Like what is that? I wanted to very specifically give you a sense of what a 14-year-old African American girl looks like, a 13-year-old African American boy. I want them to be that age as a way of invoking their presence in the work, not a presence, but their presence through those young people. And through the adults who were the same age they would have been if they had not been murdered.

48H The photos in your Underground Railroad series, Night Coming Tenderly, Black, are very dark. Why did you want them to look like that?

DB I wanted the viewer to think about moving through that landscape under cover of necessary darkness, as they moved, in that case, toward Lake Erie. I wanted to make photos that evoked that particular sensation. It kind of allowed the viewer to momentarily, through the photograph, inhabit that space under those circumstances, to imagine oneself moving though that terrain under threat of death.

The positionality of all of them is eye level and meant to be experienced as if one were the person moving through that landscape. I wanted it to be a heightened physical and psychological experience.

I had a very interesting experience at the Art Institute of Chicago when I showed them for the first time. I came into the gallery and two women had just finished looking at the work. They looked disoriented and they said to me, “You’re the one who made these photographs, right?” I said yes. “But you made them now, right? Obviously you didn’t go back, but why am I feeling I’m someplace I’m not?” It kind of pulled them back. I really want the work to pull you into the experience, so it’s not just a space of the imagination, which it is, but that it resonates as experience.