Politico recently put out an email blast asking “who’s to blame” for the COVID pandemic:

The Olympics Games are postponed, but the Coronavirus Blame Games are taking their place.

There are obviously places to look.

The New York Times says that humans moving into spaces where other species have lived for thousands of years is making this sort of disaster more and more likely.

The Trump administrationhas failed profoundly in its response to the the COVID crisis, putting the lives of hundreds of thousands of people at risk. The list of the failures goes on and on.

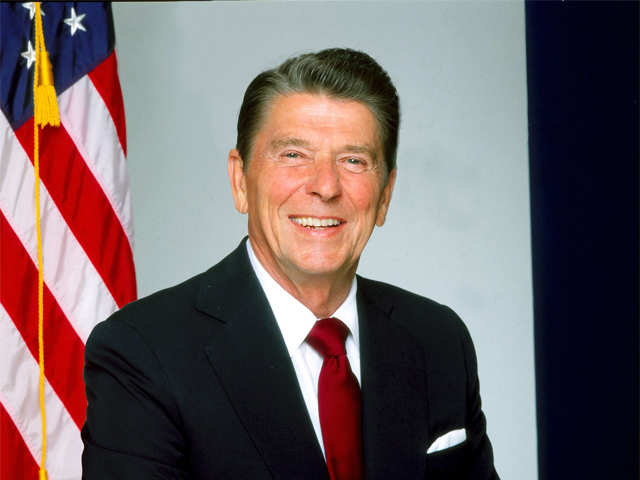

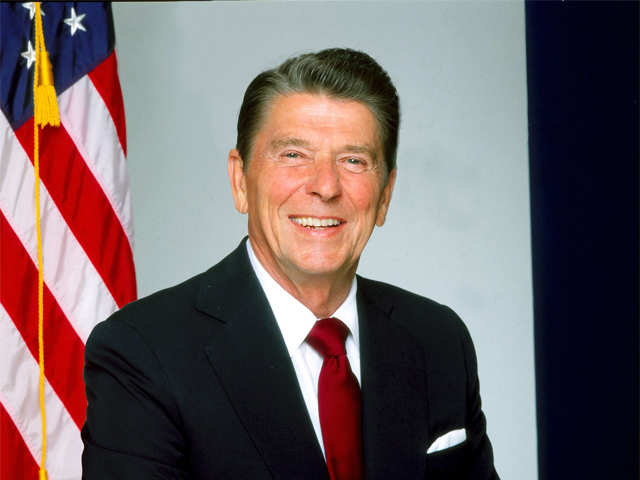

But this isn’t something that just happened under this Republican. The roots of this pandemic and our failed response go back much farther, to the days when Ronald Reagan was elected president, and the post-War American labor contract ended, globalization began – and a new era of capitalism, driven by business consultants who demanded just-in-time inventory and hospitals and health-care companies, including nonprofits, that went away from public service and into profit-making.

The election of 1980 started a half-century trend toward policies that assumed the private sector was better at solving problems than the public sector. And look where it has left us.

Back in the 1990s, I used to study martial arts with a guy who worked for PG&E. He was the equivalent of a firefighter; his job was to respond to problems. When a line went down, when a neighborhood had a blackout, he jumped in the truck with his coworkers and went and fixed it.

But a lot of the time (in those days) nothing went wrong. So he and his crew would send their time reading training manuals, practicing, teaching new people how to fix problems, and making sure that when a problem hit, they had the capacity to respond.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

And yeah, like firefighters, they had down time.

So one day a business consultant came into their workspace and started asking questions. What are you all doing all day? Why aren’t you out in the field? Why are you getting paid to do nothing?

There was only one answer: We are getting paid to be ready for an emergency, so when it happens we can respond quickly – and there will be enough of us to make sure that blackouts don’t last for days.

That wasn’t good enough for the consultant. He saw this as waste; people getting paid to do nothing. His recommendation was that most of the “excess” workers get fired.

This had been happening at American companies for years. It’s been happening in hospitals, where executives have pushed to limit rooms and reach 90 percent “occupancy” (as if a hospital were an apartment building or a hotel), leaving no extra capacity for emergencies.

It happened in the public sector, where reporters who wanted to expose “waste” and politicians who wanted to look good in the press found every excuse to shred the safety net. Hey: There’s no fire today. Why do we need so many firefighters? Hey: The hospitals have empty rooms, and the taxpayers are on the hook; why don’t we eliminate some nursing positions?

The financial crisis of 2008 caused massive cutbacks on public services. When the crisis was over, and business was booming again, those cuts were, for the most part, never restored. Instead, government and business both decided that “gig economy” workers, who could come and go as needed, and inventories that would never sit around idle, were a great solution.

Tax cuts for big business and the very wealthy were never repealed.

And corporate profits soared, and the rich got much richer, and income inequality became so obscene that it should have been the defining issue of our political time.

Nobody could have been fully prepared for this crisis – although epidemiologists and virologists have been warning for years that something like this was likely, if not inevitable.

But the US could have been a lot better prepared – if policy makers had decided that critical medical supplies needed to be manufactured near where they are needed, not as part of a global supply chain that depended on terrible labor exploitation; if policy makers had decided that the public health system was too important to be run by private companies (and huge nonprofits) that cared first about money; if policy makers had decided that it was more important for sick people to see a doctor than for private insurance companies to make profits.

Why don’t we have enough ventilators, and testing capacity? Because that would be “inefficient,” according to the business consultants at places like McKinsey who have defined late-stage capitalism. Why don’t we have a robust public-health system? Because it costs a lot of money, and would require that the 2,000 billionaires in this country accept just a little bit less wealth so the rest of us can survive.

I believe and hope that we, as a society and species, will get through this. The economy will recover; life at some point will get back to something resembling “normal.”

But if we don’t stop at this point to think about the role that globalization, privatization, and late-stage capitalism played in reducing our society to this level, and causing this many deaths, the new “normal” will just be more of the same.