“I just want to say one word to you. Just one word. Are you listening? Plastics!”

This line, spoken to Dustin Hoffman at an unbearable cocktail party in 1967’s The Graduate, encapsulates the cultural schism around synthetic polymers. The earlier generation, reared on heat-resistant wonders like Bakelite, saw postwar American ingenuity, Better Living Through Chemistry, the future itself. The kids saw garish, manufactured crap.

Fifty-four years later, the ocean is swirling with indestructible garbage, photo-degrading into ever-smaller pieces like Boomer rebellion curdling into nihilism. We know our planet is dying, but Costco still sells shrink-wrapped three-packs of cucumbers that are each individually shrink-wrapped. Amid anti-vax paranoia and a cultural aversion to unspecified “chemicals,” we barely think twice about sealing a vegetable (that comes in its own peel!) twice over with polyethylene.

This schizoid attitude towards our teetering era of super-abundance characterizes “In Balance,” a new show at Heron Arts. Opening on Sat/28 with a reception from 7-10pm (the show runs through September 25), it includes work by Casey Curran, Dyanna Dimick, Helena Garza, and Spencer Keeton Cunningham, as well the Detroit-based manufacturing studio Thing Thing. The focus is the Anthropocene, the current geological epoch in which Homo sapiens appears destined to annihilate entire ecosystems before snuffing itself out.

That’s the bleakest possible interpretation, of course. The art at “In Balance” isn’t nearly as pessimistic; if anything, it’s the opposite. Saving the world means new ideas — and for Thing Thing, reworking methods and repurposing methods is the point. Co-founder Simon Anton’s partnership with artist Lorena Cruz Santiago, a NorCal native who lives and works in Michigan, aims for a sweet spot between modern materials and indigenous craft.

“We made a set of trays and platters and vases that stack on top of each other to create a sculptural domestic piece that is all about fusing contemporary plastic and contemporary plastic-recycling methods with much older weaving styles,” Anton says, “to create a conversation between two things that seem like they might not be related but have a lot to say to each other.”

Cruz, a basketweaver who learned her techniques in Oaxaca, says that “the plastic in weaving has a certain amount of permanence.”

She notes that palm leaves are so tough and fibrous that the leftovers resemble human-made plastic trash. (Indeed, the fronds are essentially un-compostable.) So she took advantage of that durability to make an ephemeral art form more stable.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

“When I’m thinking about plastics in weaving traditions, it allows for these objects to become permanent in a way they weren’t before,” Cruz says. “Ancient baskets don’t really exist.”

Anton, who admits to a love-hate relationship with plastic, is hopeful about its applications.

“The idea of combining the handicraft with the plastic also talks about a way of being in the world where you’re using ancient, embedded knowledge and you’re able to make bridges with the crazy mess of our world right now,” he says. “Plastic comes from an offshoot of the oil-extraction industry, and oil and stones in the earth have been interacting in the same spaces together for millions of years. Putting them intentionally into conversation again, in a piece that supports human domestic life, reframes the conversation.”

When pondering our potential impending environmental collapse, it’s easy to conclude that systems and institutions create and destroy things at such a rate that there’s nothing that ethical people can possibly do about it. Anton and Cruz’s prosumerist practice uses this discouraging dilemma as a jumping-off point. They maintain that it’s about cultivating a need to do something, however futile in the grand scheme of things, if only to maintain that spark of human autonomy — similar to the mood that infuses the Netflix documentary A Plastic Ocean or the Anohni album Hopelessness.

“I don’t know if necessity is the word, but regardless of the ecological disasters we’re facing, there’s still a desire to create,” Cruz says. “I give into the idea of hopelessness a lot, but my work is a way of fighting that, I guess. I don’t ever want to say that my work is going to solve any problems, or that as artists we’re required to have solutions, but there is a necessity to make the work, anyway.”

A major pitfall for socially-urgent art is, of course, its tendency not only to preach and shriek but to become very impressed with itself in the process. (Take a look at Gay Shame’s current display at Artists Television Access, an anti-gentrification statement targeting fnnch’s honeybears that’s a little too in love with its own self-righteous virulence—and also several months past its expiration date.) For Dyanna Dimick, who’s also part of “In Balance,” making change through art is about showing things in a “kindhearted, bright way that’s also approachable.” Honey before honeybear vinegar, in other words.

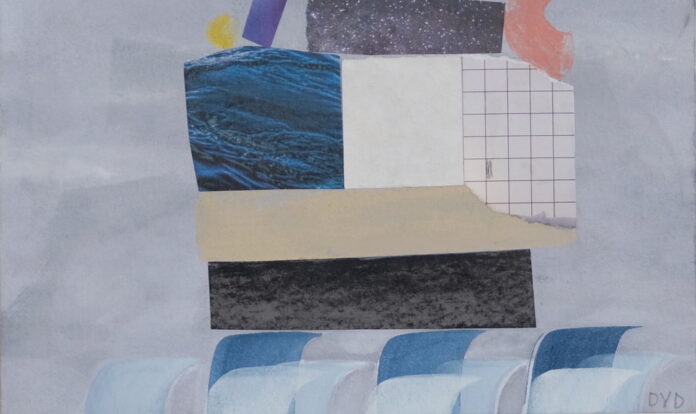

A graduate of UC Santa Cruz—where “you can’t help but have a relationship to the environment because it’s such a gorgeous place,” she says—Dimick builds collages out of found materials, highlighting the fact that disposable and beautiful are not mutually exclusive. Her oceanic, blue-heavy palette gets a great deal of traction out of business envelopes, bar codes, scraps of animal print, and charred cardboard. To generate these results, she operates with a few aesthetic constraints.

“I buy acrylic paint, even though it is plastic,” she says. “Oil paint is a different beast. I try not to go out and buy new canvases. I try to get raw canvases, or when my friend has one that they painted on, instead of buying something new. I use old papers that people give me — sometimes they’re acid-free and sometimes they’re not. I use a lot of what’s around my house, even though there are certain things that I can’t help but buy that come with materials that are non-recyclable. Or I can’t throw away this little piece of plastic, so I save those and work those in.”

Dimick’s output during the pandemic has become smaller in size. (“I had to work at home, and at home I have a very tiny desk,” she says.) She expresses a desire to work at a larger scale to grab people’s attention, but she’s comfortable with intimate pieces that require the viewer to go up and study them. There’s a kind of mundane pantheism to her work, in which even a piece of junk mail feels reconnected to the tree it came from, and to the sea that will eventually absorb the envelope’s plastic address window.

“I want to give people a little bit of what they’re familiar with and a little bit of what they might consider trash,” Dimick says. “Little baby steps.”

After the last year-and-a-half of horror and boredom, it’s starting to look as though American appetite for post-apocalyptic themes has finally been satiated. (It’s exhausting just to learn that The Walking Dead is on Season 11, let alone watch it.) But Afghanistan and wildfire season notwithstanding, civilization is still very much in the pre-apocalypse phase. “In Balance” demonstrates that the artistic path out of dystopia is actually an active, hopeful one. The materials are all around us, a bit little more every day.

IN BALANCE Opens Sat/28 7-10 p.m. and runs through September 25, viewings by appointment. Heron Arts, SF. More info here.