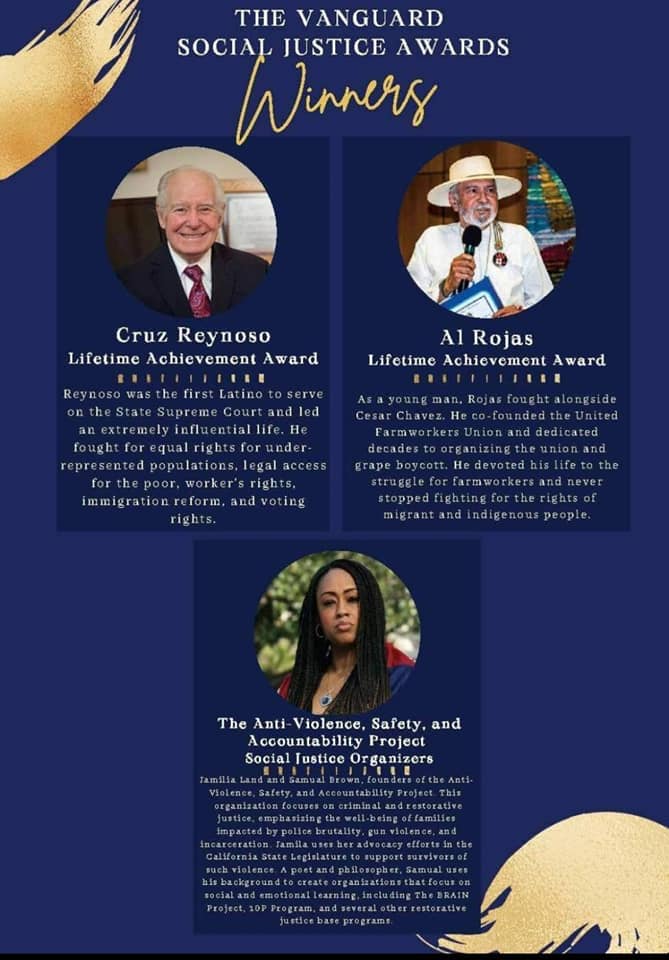

Jamilla Land, co-founder of the Anti-Violence, Safety, and Accountability Project, was in Sacramento tonight to receive a Social Justice Award from the Davis Vanguard. She was honored along with the likes of Cruz Reynoso, the first Latino state Supreme Court Justice, Al Rojas, co-founder of the United Farm Workers Union, and the University of San Francisco Law School Racial Justice Clinic.

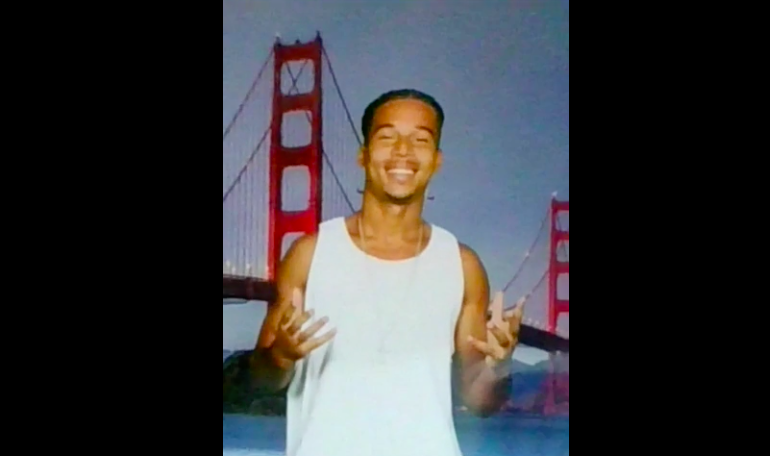

A few hours earlier, this afternoon, I was on the phone with Land, her husband Samual Brown, and her son, Elijah Johnson. We were talking about COIVD in state prisons. Both Brown and Johnson are incarcerated.

COVID continues to be a huge crisis behind bars (including a huge outbreak at Santa Rita, the Alameda County jail) although the news media interest has largely waned. But combined with the wildfires and their proximity to numerous state prisons, this has been a terrifying month for California prisoners.

Johnson is locked up in the Sierra Conservation Center in Jamestown. He told me that he’s been suffering from COVID for two weeks, and is still feeling symptoms. He’s had coughing, diarrhea, fatigue, and dehydration.

He’s been confined with as many as 50 other men in a gymnasium at the prison complex. There is no social distancing. There has been essentially no medical attention. Just once, a doctor came in and checked his name off a list; that was it, Johnson told me.

“They are sending individuals back to their cells who still have symptoms,” he said.

They are double-bunked, with nothing but a sheet to separate them from the other inmates.

And the fires have been close.

Lt. Ricardo Jauregui, a spokesperson for the prison, told me that 28 prisoners were currently isolating for COVID. Johnson said the number was much higher. At least three and sometimes as many as five more inmates arrive in the gym every day, he told me.

Land didn’t find out that her son was sick for two weeks (the Vanguard was the first to report this story). That was in part because a wildfire came so close to the prison that it burned up the phone poles.

“It was ten miles away, the only issue was the telephone lines,” Jauregui told me.

But that’s not what it felt like inside.

“The smoke was blowing all over the facility,” Johnson said.

So what happens if a fire threatens a California state prison? Plans are, at best, sketchy and limited.

Take a map of state prisons, and overlay it with a map of high-danger fire zones, and you get a pretty good match. In fact, according to the Public Policy Institute of California, 65,000 inmates are within five miles of a hazard zone.

What would the state do with all of those people if the fires were an imminent threat? It’s not clear. Jamestown, for example, has a large number of infected prisoners; the other state prisons, which are trying to keep their numbers down, won’t want those transfers.

Brown told me that in Los Angeles, where he is incarcerated, “there are fire drills for the staff, but not for us.”

Johnson told me that as the smoke began to foul the air and the phone lines went out, “we were never informed of anything by the correctional staff.”

Brown told me: “It’s as if we are not even human beings.”