If San Francisco wants to meet its state-mandated affordable housing goals, the city will need to find roughly $19 billion of local money over the next eight years—and nobody at the Mayor’s Office or the City Planning Department has any idea where that kind of money will come from.

In fact, officials from those departments can’t even explain what the current funding gaps are, or have been in the past three years.

That’s the takeaway from an astonishing hearing today at the Board of Supes Government Oversight and Audit Committee.

Sup. Dean Preston, who called the hearing, said he wants to know how the city plans to meet the new state goals, known as the Regional Housing Needs Assessment.

Under legislation pushed by state Sen. Scott Wiener and others, the city is now required to authorize about 80,000 new housing units over the next eight-year cycle, and 46,000 of those need to be at below-market-rate levels.

Upzoning to allow developers to build more luxury condos will fill the market-rate goals, even if that housing never gets built. But affordable housing has to be funded.

The state rules, in a bizarre twist that only Wiener and the Yimbys could love, say that cities failing to make those goals can lose state affordable housing money. But the state offers no specific funding to help make the affordable housing goals happen.

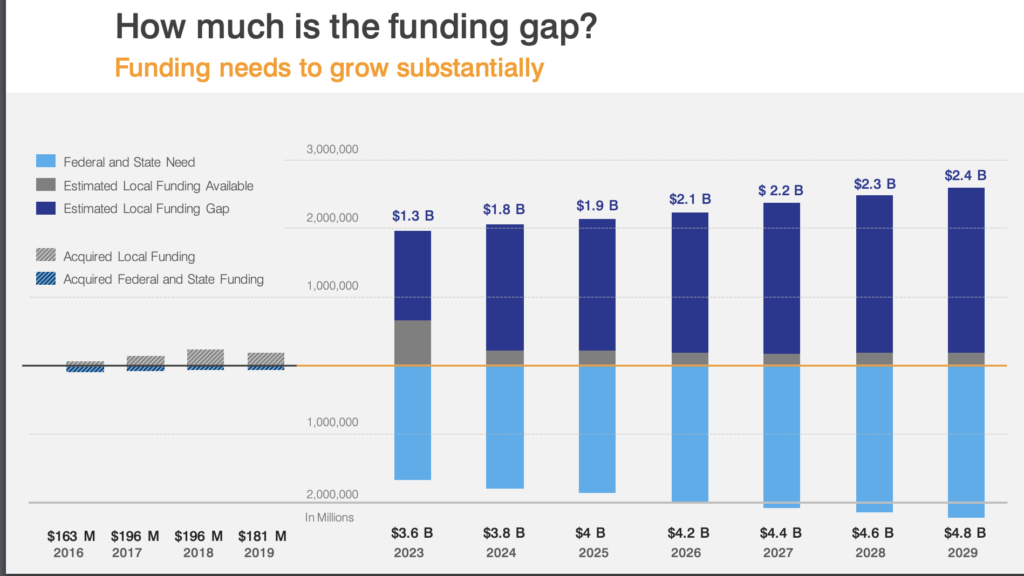

The numbers are incredible: Every year, the city will be somewhere between $1.3 billion and $2.4 billion short of the local revenue that’s needed to create nearly 6,000 affordable units. (Since most affordable housing in San Francisco is built by nonprofits, those organizations will also need substantial funding to expand their capacity to find, acquire, and develop sites.)

During the hearing, Preston asked repeatedly how the Mayor’s Office plans to find that money—and the answers were, at best, vague. Among their suggestions:

Continued advocacy at the state and federal level: Regional Funds such as Bay Area Housing Finance Authority (BAHFA); Prop 13 Tax Reform; State actions including surplus land, adaptive re-use funding; Federal actions, for example Build Back Better, Housing Supply Action plan.

But Lydia Eli, deputy director of the Mayor’s Office of Housing, acknowledged that relying on future state and federal funding was risky at best. The BAHFA money is competitive, and San Francisco might not get its share. There’s no reason to believe that if the Republicans control Congress after the mid-terms, any new federal money will be available. And efforts to reform Prop. 13 in the past have failed.

In fact, federal money night shrink, which is why SF’s local burden will increase over the next few years.

The current RHNA goals are much lower—but San Francisco isn’t close to meeting those right now. The city has approved and allowed developers to build far more market-rate housing than the state wants, but is way behind on affordable housing.

But Eli couldn’t explain how far the city has fallen behind on financing between 2018 and today.

Preston asked if the Mayor’s Office of Housing or the Planning Department had requested that Breed spend the Prop. I money on housing. The clear answer: No.

“It’s unbelievable,” Preston told me after the hearing. “They can’t even tell us what they’ve done for the past three years, and there are orders of magnitude greater in the next few years…. If there were ever a moment to spend the Prop. I money on affordable housing, it’s now.”

Preston said the message was alarming: “It’s not acceptable to say we aren’t going to meet the goals and say we have no plans to do it.”

Let’s consider reality here. The only way the city can possible meet the RHNA goals is to dream about state or federal funding (and Gov. Gavin Newsom has made it clear he’s not spending more than a small fraction of the state’s record surplus on affordable housing)—or find ways to raise more local revenue through taxes on the rich.

That, or fundamentally shift the city’s funding priorities by, say, cutting the police budget, which the mayor has made clear she won’t do.

Breed has never supported measures to make big business and big landlords and speculators pay more for affordable housing. But now she’s going to run into a state-mandated mess.

“This is very difficult to listen to,” Connie Ford, a longtime labor activist working with Jobs with Justice, told the committee. “We are in a crisis.”

And the crisis will require the mayor to work with, not against, the progressive majority on the board. Or it’s going to get a lot worse.