Apple, which was one of the leaders in bringing workers back to the office, just announced it’s suspending that policy because of a new Covid spike.https://www.nytimes.com/2022/05/17/technology/apple-delays-return-to-office.html Others will follow.

But the spikes are just the beginning: The pandemic has changed some types of work, particularly office work, forever, and cities like San Francisco are going to have to get ready for it.

Let’s consider something that might be a real possibility: Suppose that somewhere around half of the former downtown workforce never returns to the office?

Or maybe it’s 25 percent. Or 20 percent. No matter: The pandemic and Zoom made telecommuting a thing, and lots of former office workers liked working from home, and even companies that do require workers to come back to the office probably won’t require them five days a week, which means they won’t need as much space.

As much as Mayor London Breed and the Chamber of Commerce would like to welcome all the workers back, a big chunk of the city’s 80 million square feet of office space is quite possibly never going to used as offices again.

That has huge economic implications for the downtown area and so, so many things, from small business to Muni and BART, that depend for revenue on commuters heading into downtown San Francisco.

Since the end of World War Two, nearly all major development, and nearly all of the city’s economic policy, focused on a downtown financial district with highrise office space. That’s why BART looks the way it does; it was designed to bring commuters downtown. That’s why the Muni lines look the way they do.

Office space replaced light industry and blue-collar jobs. San Francisco in the early 1980s still had a robust and thriving printing industry in Soma; it’s almost all gone, displaced for office space, which paid higher rent per square foot.

So the usual economists and developers and pundits are starting to ask: Why don’t we turn all the empty space into housing?

The reason that most of downtown San Francisco is office space, not housing, has nothing to do with “Nimbys” or downzoning or any of the other stuff that the Yimby movement wails about. It’s simple economics: Developers and the institutions that finance them decide what to invest in, and for most of the post-War era, office space was more profitable than housing.

So now, maybe if office space isn’t going to be profitable any more, and office rents are going to fall dramatically, and there’s still a lot of demand for housing in the city, it might make sense to shift the use of that space.

In theory.

In practice, it’s difficult, since living space and working space have very different code requirements, and everything from bathrooms to windows and outdoor access makes it perhaps prohibitively expensive to do conversions—particularly if we want housing that’s not all luxury condos.

The guv, always ready for a press conference, says maybe the state can put up $600 million to help. That’s 0.006 percent of the state’s current budget surplus to address perhaps the biggest issue in urban California. It fits into his overall plan, which offers almost nothing for affordable housing. That money won’t pay for even a tiny number of conversions in a couple of cities.

Or maybe we’re looking at this entirely the wrong way—and Soma in the late 1970s and early 1980s might offer us some creative ideas.

As warehouse and industrial operations started to move out of the city in that era, a lot of old brick buildings were left empty. A decade later, they would be demolished for office space or transformed into cool, hip centers for the first dot-com boom. But for a while, they were empty.

And artists moved in.

Sometimes, landlords rented the buildings as “studio space,” getting a least a little income instead of none, and they looked the other way as the tenants turned the industrial space into living space. Sometimes, squatters moved in, and colonized empty space themselves. But the Soma loft culture was real, extensive, and entirely DIY.

Low-income artists and musicians didn’t care if they had to share bathrooms, or if they didn’t have balconies, or if they had to build out their own places, hang their own sheetrock, build their own lofts, sometimes (and it could be far from optimal) do their own electrical work.

The city looked the other way, too, because the landlords didn’t care. They were looking at zero income or some income; the choice was obvious.

DIY warehouse space has been, at times, a massive, even deadly, problem. But maybe, in modern highrise office buildings, it might be possible to reach a solution that makes sense for everyone.

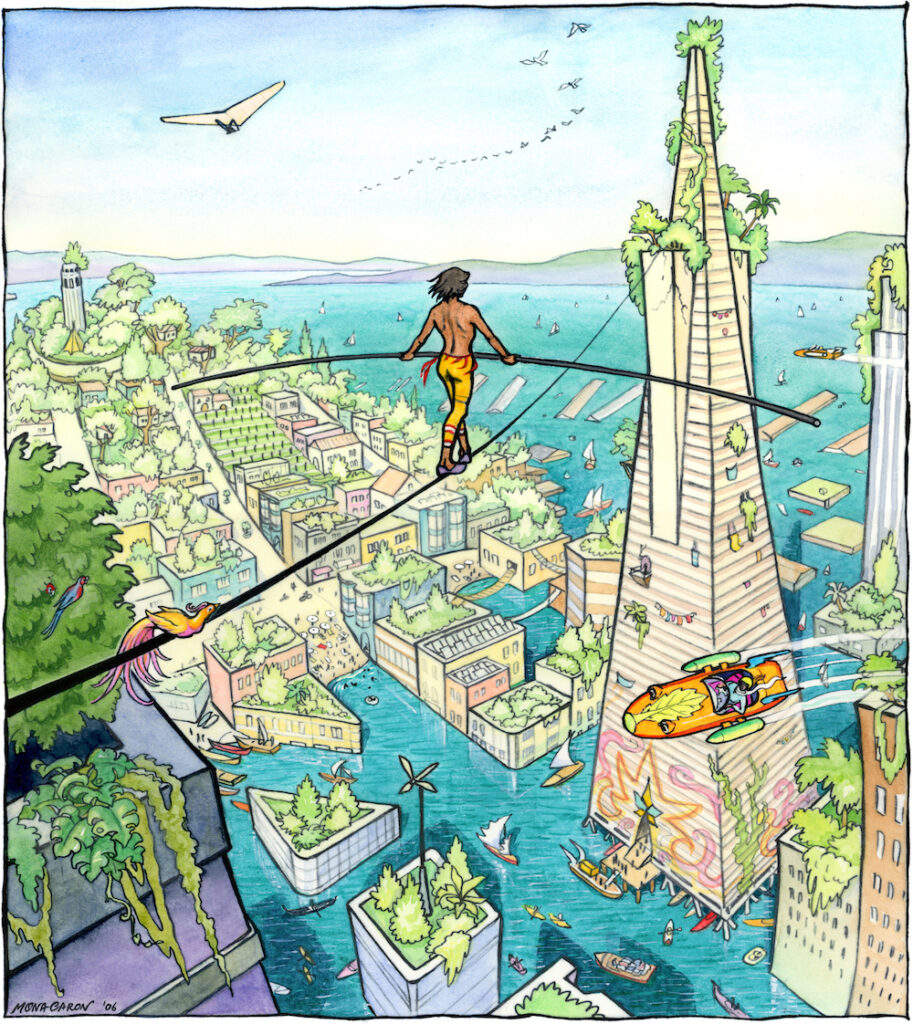

What if San Francisco (and the state could clearly help with this) took over the leases for some of that worthless office space, at a huge discount (landlords: You can get some money, or no money. Choose). And what if we put out the word worldwide that we were looking for, say, 5,000 artists—painters, musicians, photographers, performers—to come to downtown San Francisco to build out empty office space into art communities?

What if we changed the building codes to make this possible—and hired union electricians and plumbers to come work with the DIY artists to make sure that nothing was a fire trap? (There’s no way the Salesforce Tower would become another Ghost Ship; among other things, it has code-mandated sprinklers.)

Artists go to cafes. They go to bars. They ride Muni and BART. They could revitalize downtown in an amazing way.

We could also follow the model of Homefulness in Oakland, a community living situation built by and for homeless people. With just a little bit of help, the folks at Poor Magazine, who built Homefullness, could expand that experiment into empty downtown buildings.

Or: We could let that space sit empty, while the arts community in the city continues to be devastated by high rents and a lack of space, and thousands of homeless people live on the streets, and just hope that office workers will eventually come back.

Seems like a pretty clear choice to me.