Some of the best and most informative exhibitions covering our city’s politics, art, and history are to be found in the unpretentious basement Jewett Gallery in the main branch of the San Francisco Public Library. Exhibitions that have come through the space include the 2013 show of stunning documentary photographs by Phiz Mezey, capturing the scale of Redevelopment’s devastation. Visitors have seen images of the early performances of the Coquettes, the 1969 Native occupation of Alcatraz, and the marches on City Hall that demanded action on the AIDS epidemic.

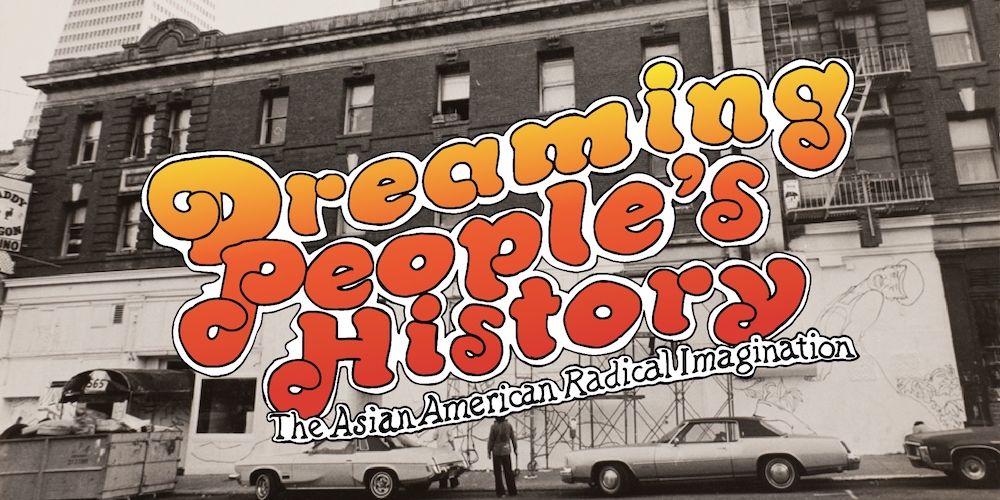

“Dreaming People’s History: the Asian American Radical Imagination,” (runs through August 6) organized by Colin Choy Kimzey and the Kearny Street Workshop in the Jewett, is a thoughtful and thorough reflection of the history of radical Asian American movements in San Francisco. It makes an important addition this ongoing list. A panel discussion with the exhibition’s curators and participating artists will take place in the library’s Koret Auditorium on Sat/15.

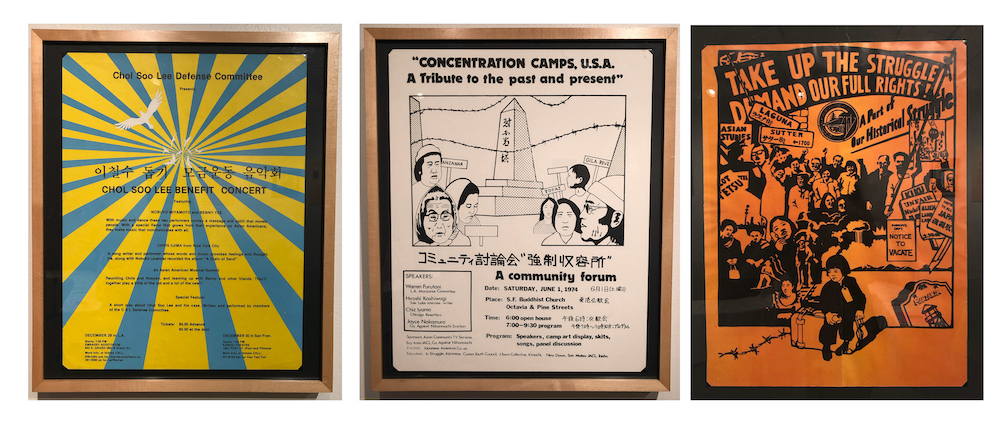

At a time when Asian identity has been weaponized in relationship to carceral and anti-Black policies, “Dreaming People’s History” corrects both historical narrative and current discourse. The show’s focus on Black and Asian solidarity, tenant and working-class power, and anti-imperialist internationalism couldn’t come at a more important time.

The exhibit opens with an unforgettable site in San Francisco history: the I-Hotel. The massive SRO on Kearny Street was once home to a generation of Filipino elders whose defense became the cornerstone of a city-wide solidarity movement.

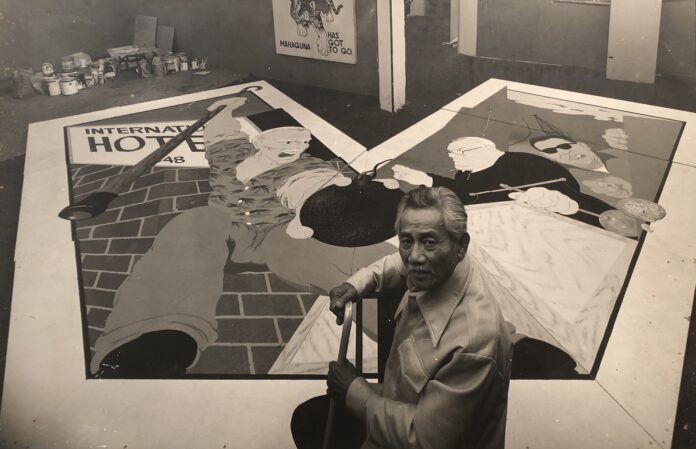

The aptly named mural, “The Struggle for Low Income Housing” (1976), depicts the battle over the International Hotel, as well as partners in the struggle for its survival. (The Kearny Street Workshop, the Chinese Progressive Association, the Asian Community Association, and the I-Hotel Tenants Association, I learned from this exhibit, were all once housed in the I-Hotel’s ground floor.) In the mural Manilatown elder Felix Ayson, holding a cane in one hand and halting the swing of a wrecking ball with the other, faces off with a judge and developer.

According to the artist Jim Dong, the original mural was most likely accidentally destroyed while in storage at the Mission Cultural Center during a controversial transition in leadership. Thankfully, a remarkable photograph exists of Ayson, seated cane in hand in front of his own likeness.

Standing in unambiguous opposition is a photograph of San Francisco Sheriff Richard Hongisto, wielding a sledgehammer against an I-Hotel tenant’s front door. After winning the trust of residents and the public by pledging never to evict the hotel’s residents, and notably spending time in jail over contempt of court, Hongisto became something of a people’s hero. Eventually, the sheriff capitulated to City Hall, and under developer pressure, delivered the eviction’s first symbolic and literal blow himself. An onlooker remembered the moment, all other feelings aside, as being extremely awkward; Hongisto was posing for the shot wearing a suit in apparent anticipation of a date later that evening.

Selling out is nothing new in San Francisco. San Francisco’s first “progressive” sheriff would later go on to become the chief of police and become infamous once again, first for his draconian handling of San Francisco’s Rodney King riots, and then for ordering the confiscation by SFPD of hundreds of gay newspapers that portrayed him in a critical light, an action for which he was finally fired. Other aspiring political figures who were once public supporters of the I-Hotel struggle—among them, Hongisto, Jim Jones, Ed Lee, and Willie Brown—went on to join San Francisco’s power establishment.

And while inclusion of the surrounding context of this episode may read as something of an aside, it is important evidence of the extreme swings of radical and reactionary politics in San Francisco. Any singular piece of political-historical-artistic ephemera in the exhibition provides an entry-point into this tenuous world.

The nine-year struggle for the I-Hotel was for a decade the center of a powerful coalition of radical movements in San Francisco. Its eviction gave the community an idea of both what could be achieved through political solidarity, and what could be expected from City Hall.

More of these lessons are to be found in Andrew Szeto’s Heartbeat of Struggle #1, a zine produced through the Kearny Street Workshop that is distributed for free in the exhibit. In it, Szeto traces the history of radical Asian American struggle backwards though time. They begin with San Francisco’s successful fight to stop a new jail from being built in 2020, a demand won during the powerful-albeit-temporary national reckoning amid the George Floyd uprising.

In the course of their recollection, Szeto touches on the poetry of Al Robles, the murder of Vincent Chin, the wrongful conviction of Chinatown’s Richard Lee, casts a critical eye on the support campaign organized on behalf of the Chinese American cop who killed Akai Gurley, and describes their own experience moving to Detroit to follow in the legacy of Grace Lee Boggs.

The exhibit’s curators have also put together a series of primers on the history behind the murals, poetry, and silkscreens of the San Francisco’s Asian American movement.

Clearly formative to the development of an Asian American political consciousness regarding prisons and imprisonment was the internment of Japanese Americans in WWII (the historical event to which the term “mass incarceration” was in fact first applied.) This consciousness was the foundation of Asian American prison abolition movements and the formation of a robust prisoner support movement at which Asian Americans have often been at the fore.

Yuri Kochiyama, incarcerated in an Arkansas internment camp for several years as a teenager, later became a close personal friend and confidant to Malcolm X and an ally to the Black power movement. Jeff Adachi, whose parents were interned, went on to become San Francisco’s most well-respected public defender. Adachi perhaps best embodied and articulated the oppositional role of the criminal defense attorney within the so-called criminal justice system.

“Political struggle,” says Yuri Kochiyama, as quoted in Szeto’s zine, is “a contagion of motivation, a chain reaction.” “Dreaming People’s History” reminds us that there is a strong, viable vein of revolutionary struggle that runs through history, without a beginning or an end.

DREAMING PEOPLE’S HISTORY: THE ASIAN AMERICAN RADICAL IMAGINATION curator/artist panel discussion Sat/15. Exhibit runs through August 6. San Francisco Main Library. More info here and here.