The simultaneous strength and setback of Citizen (through November 12 at Z Below, SF) is its dreamlike nature. Greg Sarris’ tale of a young Mexican-Native American man is structured less like linear story and more like a flood of memories that come rushing back. Its theatrical use of an ensemble cast almost suggests the way memories blend into one another and faces begin to resemble one another. AI may have all the precise categorization of digital automation, but it still hasn’t figured out the beauty in the madness of abstract thought.

Unfortunately, dreams can be notoriously hard to recall for those unpracticed. So, too, is Citizen frequently hindered by its expeditious mash-up of past and future. Details and characters zip by so fast that one doesn’t always keep them straight. Plus, the supposed motivation for the entire plot is dropped halfway through, so one is left wondering what the story itself meant at the end.

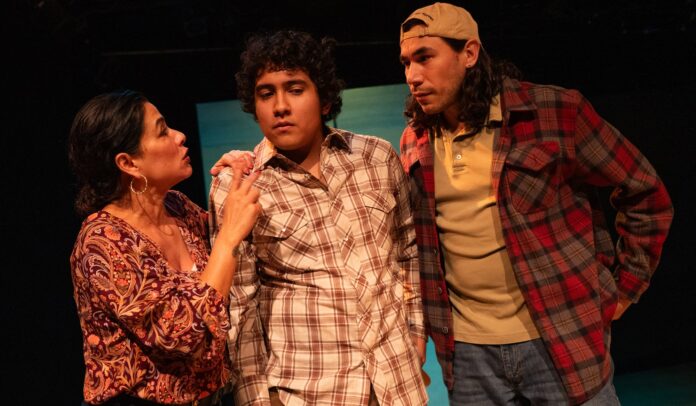

Said story revolves around Salvador (Christian Jimenez), the US-born and Mexico-raised young man who’s come to the States to see his mother’s grave. He leaves behind his frequently-philandering father—now remarried with several new kids, and at least one mistress—and his brother, whose recent dalliance with a young girl resulted in a shotgun wedding.

Salvador ends up in the rundown apartment of his aunt Eldine (L. Duarte) and her son Marco (Ixtlán). It isn’t long before the cash-strapped Salvador finds himself next to Marco in a queue of day laborers, hoping that someone rich and white needs work done, be it around the house or in one of California’s many vineyards. Fortunately for Salvador, being born in the US opens up a great many legal opportunities. But it also makes him a target for anyone willing to exploit his ignorance.

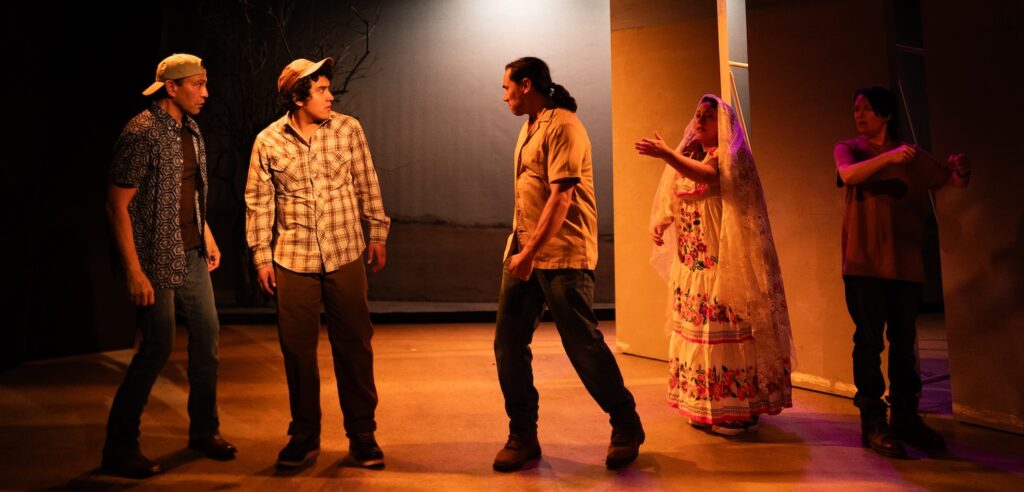

Like many of Z Space’s Word for Word entries, Citizen isn’t a proper play so much as a story put on its feet. Every person on stage reads both their own dialogue as well as the descriptive settings of the scene. It certainly works to set the scene, with Mikiko Uesugi’s actual set consisting of only three moving wall pieces, a wide vista painted on the upstage wall, and a tree upstage-right. As such, it’s necessary for Salvador to describe the dirty details of Eldine’s apartment building and the children who run past him down the corridor.

It also helps in its depiction of the immigrant experience. Eldine knows that if Salvador is to take advantage of his citizenship, he has to prove he’s a citizen. We feel Salvador’s confusion as he, who doesn’t speak English, is pulled by Eldine from one office to the next to get his Social Security card and CA driver’s license. Those are confounding, soul-crushing activities for someone who already speaks English; here is the perspective of someone who doesn’t.

Yet, the front-half of the story leans heavily towards “exposition dump”, trying to fill in as many details about Salvador and his family before taking some sort of respite when he finally gets to the US (a journey which isn’t explained in detail). It’s good that the story starts to take its time then, but the journey to his mother’s grave—the driving motivation of the first half—comes and goes so quickly that it almost seems an unimportant goal.

It’s one of those elements that works better as a written story than a stage production. With the former, the reader sets their own pace and can contemplate time on their own terms: we can imagine that Salvador spent a considerable amount of time at the grave, perhaps even speaking to it, before he walked away. But theatre makes the viewer more conscious of the passage of time because of the performers’ physicality. That’s why it seems to a theatre audience as if he saw the grave, shrugged his shoulders, and never thought of it again. Hopping mediums doesn’t always result in a one-to-one translation.

As a stage production, it would have probably worked better to dedicate more time to Salvador’s integration into US social norms. At one point, he begins earning enough money to where he consciously plots to assimilate. Make of that what you will, but we never quite see what it is he wants to assimilate into. He hops from job-to-job, but we almost never get to know any of his fellow workers. He often works alongside Marco, but Marco and Eldine are quickly established as people not to be trusted; Salvador never really has any connection to them as family, nor are we privy to their personal motivations and goals.

In a short story, this wouldn’t be much of a concern, as its first-person narrative would easily be chalked up to the subjective recollection of a young man telling an anecdote. But this is a stage production, and the result is the wonderfully talented cast winds up portraying thin characters who are only archetypes recalled by the narrator.

I saw the show during a matinee, as I figured it would minimize the dangers since Z Space dropped their COVID measures. Most of the staff were masked and the audience was only about half-full, if that, with a handful of them masking. Over the course of the 90-min. show, CO² readings on my Aranet4 peaked at about 973ppm, which really isn’t bad.

As literature, Citizen probably works better as a first-hand account of the immigrant experience from someone who, technically, isn’t an immigrant. But moving it to the stage requires adjustments and clarifications that, mostly, aren’t there. As mentioned, there’s a dreamlike element that works in its favor, but it also brings a dreamlike sense of confusion that works against it. It has a fine cast, a well-used set, and assured direction by Gendell Hing-Hernández. It just needs a proper script to work as its missing ingredient.

CITIZEN runs through November 12 at Z Space’s Z Below, SF. Tickets and further info here.