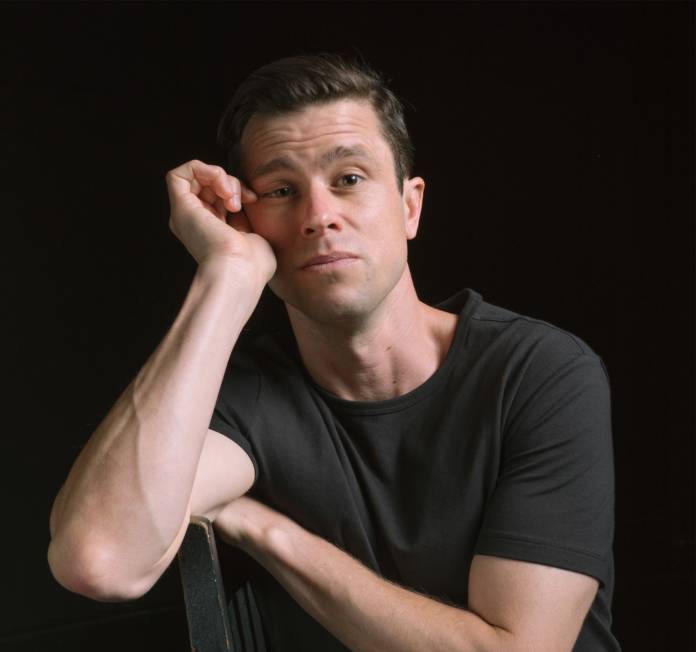

Dan Hoyle’s long-running, widely acclaimed solo show “Border People” is back at The Marsh through November 18. You should go see it.

Consisting of 11 monologues drawn from South Bronx housing projects courtyards, refugee safe houses on the northern border with Canada, and travels along the Southwestern border and into Mexico, “Border People” weaves together stories of border crossings both identity-based and geographical with tact and courage. As an Arab and an immigrant to the US, it moved the parts of me trying to piece together what has been happening back home, and gave me insight into Black and Brown people’s journeys across this country’s racial and political lines.

At first, witnessing Hoyle channel a Black navy veteran sharing his struggle to keep up with the imperatives of masculinity, followed by an Afghan student’s poignant cynicism towards his Canadian peers’ first world problems, runs the risk of dissolving specific struggles under a contrived thematic umbrella. But these stories’ proximity is also additive, especially to a non-white spectator like me. “Border people” helped me understand the universality of my migratory struggle. However different the territories we depart from and arrive in, there’s a generous liberation to seeing how we’re all united in experiences of anxious crossings, botched transitions, and clumsy landings.

In the midst of literal and figurative migrations, “Border People” invites a reflection around realness and authenticity. What is true and constant in the midst of change? Hoyle points out how, in one way, some migrants and “outsiders” are more American than Americans: They’re often entrepreneurial, rooted in family, and take the constitution to heart. Jarret, the Black veteran, is versed in the codes of Black masculinity but doesn’t let them fashion his character. Both Mike, a Mexican former marine living in Juarez after his deportation, and Larry, a Black man arrested in the Bronx for standing up for his community’s right to congregate, model how to preserve one’s sense of self valiantly, despite injustice—and even as the world’s unthinking institutions shove our lives around like the random hands of fate.

On the other hand, for some, migration means losing a precious long-sought realness. Noe, a gay man living in Mexico after deportation, lives with AIDS. He has been forced to go back to a place where he was never able to be himself. Despite how foreign Noe’s experience might seem to many of us, Hoyle explained we might be able to relate. Even if we haven’t been sent back to a country we escaped, we’ve all been people we’d rather not be anymore. We’ve all longed for people’s perception of us to keep up with our own. Hoyle’s gift to the people he interviews and portrays, is to see them as they want to be seen. His work is photographic without dipping into shallow mimicry. He captures personas with his body the way a camera’s film and a photographer’s keen compassionate eye might.

Hoyle talks with awe about his relationship with the folks who agree to work with him. I could sense how lucky he feels to be in this position. He calls his work “the journalism of hanging out.” In this view, “hanging” transforms from a mundane and unproductive activity to the rare and privileged human experience of being with people in their truth. Yes, Hoyle is a terrific performer but to admire the flamboyance of his acting is to miss the forest for the trees. It is first and foremost an honoring of the intricacies of human connection. Though fast-paced on the surface, when we peer past the entertainment, we see the result of slow and complex interpersonal weavings. Hoyle extends his people’s lives by appending his to theirs. By doing so, he amplifies their voices, gives back some of the time that was taken from them.

Since this publication last covered Hoyle’s piece, a few years ago, conversations have come to the fore around solo performers portraying multiple characters whose ethnicity they don’t share. This is a valid concern and an important point to discuss—and perhaps best left to individual viewers, especially Black and Brown ones, to decide on in the end.

Like Hoyle, I’m a solo performer and play characters who, though not of a different ethnicity—French models, Arab professors, Santa Barbara surfers etc.—are not of the Lebanese milieu where I grew up or the Bay Area community I now roam in. In one piece, I play an Italian guru whose confusing cult is a love letter of sorts to the world and his followers. The character is based on an actual Italian teacher whose neo-spiritual verbosity during a meditation they lead a group and I through left me speechless. Owing to my French-Lebanese elocution, when I shared the performance at a friend’s wedding, she thought the Italian accent was Indian. That I, a white-passing male-presenting person, was portraying an Indian religious figure felt offensive to her.

As she and I talked through the impact of my piece—and grew closer as a result—I wondered what would happen in a world where each demographic and ethnicity only portrayed people like themselves, and whether we’d forgo a doorway into radical empathy. We’re still reckoning with the filter bubbles social media have trapped us in. The consequences of the silos and echo chambers algorithms strengthen on the daily are still unfolding. We feel something’s off as we witness our personal, idiosyncratic lexicons encounter disharmony and misunderstanding in a wider sphere. We stop listening to others because we discard their experience as not ours, as other, as too foreign. “What is this?”, “I don’t get it”, “not my tribe”… “I’ll keep scrolling until something speaks to me.”

Multi-character, multi-demographic performances, like Hoyle’s, are a demonstration of how we can step into, rather than over, each other. How, maybe, in a world where home is often an undefined variable, we can be shelter for each other. While it is important to listen to the feedback of people being portrayed and take action from their words, to pre-emptively close the door to solo performers portraying different identities with the care Hoyle does is to advocate for a version of cultural respect that equates understanding with distance, and dissuades rather than promotes empathy. To close this door, without inspecting the methods and intentions with which these performances are being crafted, is to carry out a judgment as arbitrary and oppressive as that of the systems we’ve strived to topple.

I’ve scrolled past content I’ve deemed too foreign, othered people who look or think differently than me and dismissed their experience as impossible to relate to. I am guilty of that precise flavor of cynicism, and Dan’s work gives me hope. It reminds me we can hang. That the liminal spaces we call borders are full-blown worlds we’ve all inhabited at one point. That we’re all citizens of a junction, locals of a crossing.

BORDER PEOPLE through November 18 at The Marsh, SF. More info here.