Photographer Jenny Sampson’s inspiration comes from the natural and unnatural world, the work of other artists, and perhaps most notably, her job as a catering chef. She says years of standing at a stainless-steel table cleaning cases of shiitake and cremini mushrooms and strawberries, of prepping pounds and pounds of fava beans, and melting five pounds of butter in a tilt skillet has been formational. This is the ordinary minutia of her daily life.

“Had I been stuck in a fluorescent-lit office, who knows what my photographic work would look like,” she said.

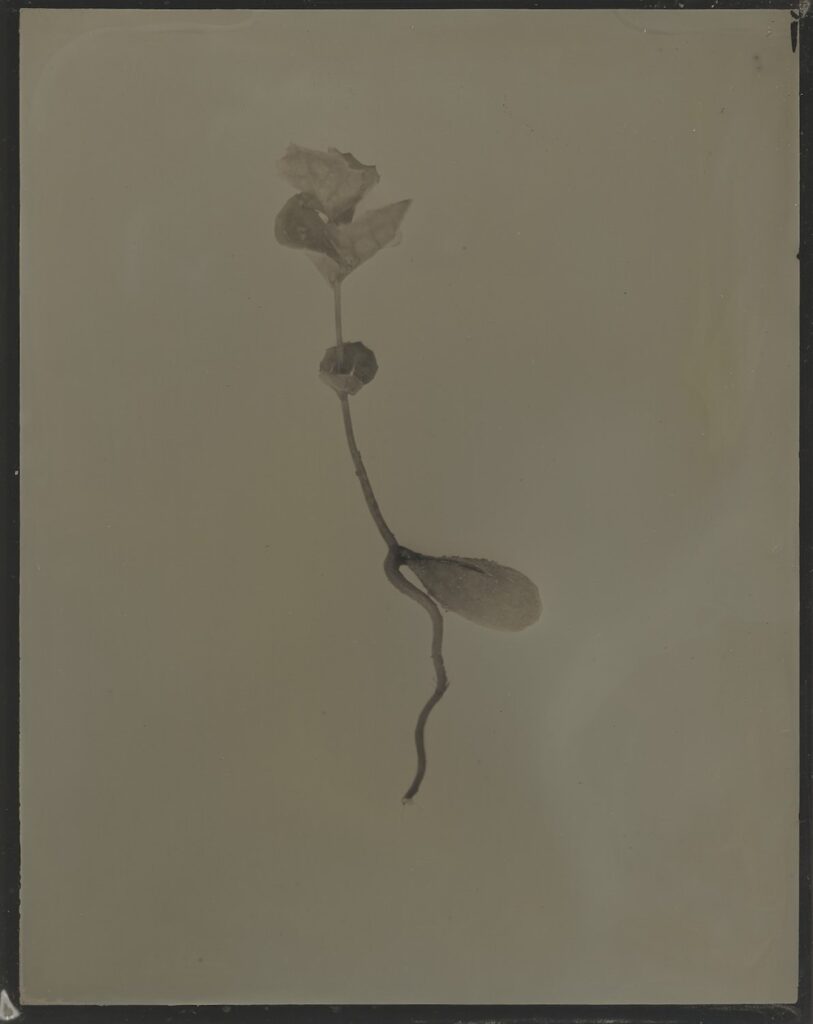

We may never know. This version of Sampson is often drawn to food in its raw state, or even flora. She often finds herself attracted to the roundness of these objects.

“I am a chef, so I have spent a lot of time looking at, handling, cutting, peeling, cleaning foodstuffs, and from that I’m moved to photograph these things in tintype form,” Sampson told 48hills.

Born and raised in San Francisco, Sampson attended Urban School of San Francisco (1987) and Pitzer College (1991) and has exhibited broadly in both solo and group shows since 2002. After a 10-year period in Seattle, she returned to the Bay in 2004 and currently lives in North Berkeley.

“The scene here is so diverse, in terms of art modality, which is important to me as someone involved with art photography. And I am deeply involved with the non-profit East Bay Photo Collective as a board member, so that combination of elements makes me feel connected to the Bay Area art community,” Sampson said.

Sampson began using a camera as a child and learned how to process and print film by the seventh grade. She says photography has always been a part of her identity, and when she had the opportunity to give it more time after college, it became even more of her world.

“At that time, I was trying to discover who I was and who I was going to be. I was drawn to other artists and creative types in my twenties, and though I had access to this community, it was intimidating and I didn’t know if I could belong,” she said.

By the time she entered her thirties, she was just out of a 10-year relationship and in an emotional space where it was comfortable and possible to explore life in a new way.

“I was becoming more confident. I was meeting new people, a world of creatives. My eyes were opening, and I was discovering that perhaps I already was an artist,” Sampson said.

As for guidance, Sampson says she is fairly self-driven and influenced by the commitment of others to their work. She self-imposes deadlines to keep the wheels turning. Describing her work as tactile, empathetic, playful, and quirky, she captures her subject matter primarily through techniques defined in film, wet-plate, and polaroid, aiming to present enduring images.

Utilizing several spaces in her home; an office, back patio, and smaller bedroom, Sampson leaves projects out in various stages, allowing for quick access. The organization of time is an integral component in her process. During the pandemic, she began folding collage into her photographic process, after years of pondering and collecting materials for the transition.

“Since the two practices demand different ways of working, a day in my studio varies considerably. If I am making tintypes, I must set aside at least two to three days for a solid run,” Sampson said.

Her process plays out like this: Day one is setting up the darkroom, her chemistry, and reviewing recently completed tintypes to inform where to focus her attention. Then she creates a series of test plates that, she says, if lucky will result in a few good plates. On day two, she has positioned things so she can dive right in, having completed the primary leg work.

“If I am in reviewing mode, whether it be of tintypes or photographs, framing or collaging, I usually spend a day cleaning and organizing my office studio first, making way for both physical and emotional space,” she said.

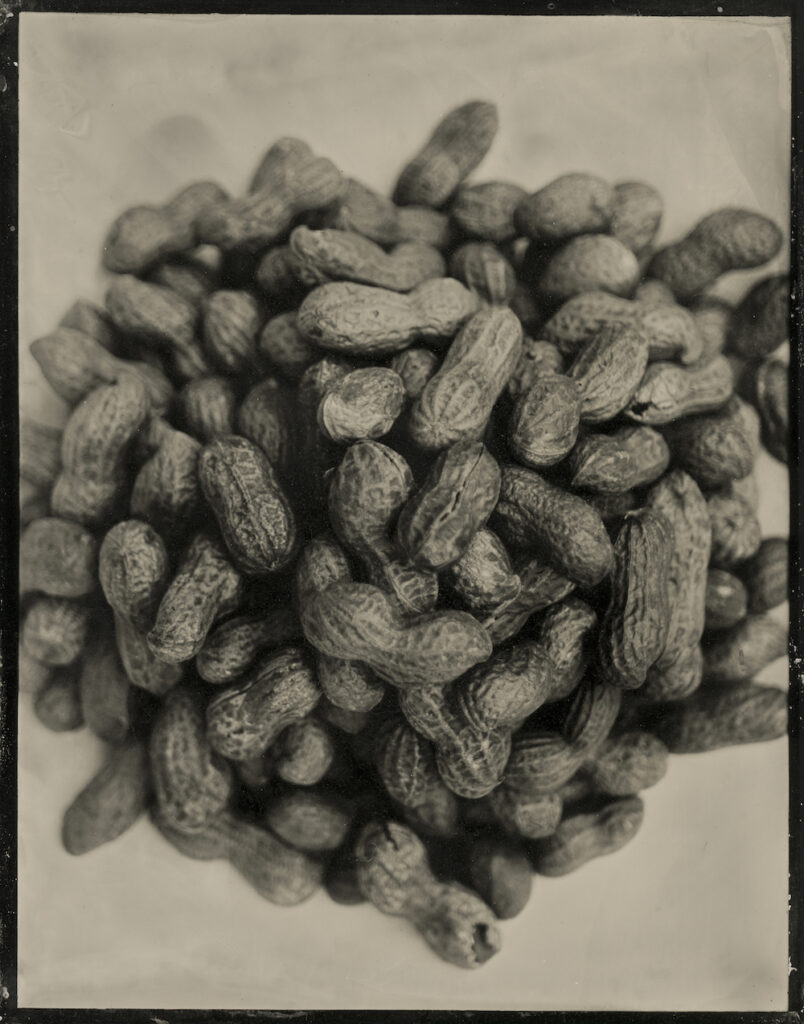

Her traditional film darkroom is in San Francisco, and she will often stay with her mother or sister, who live nearby, so she can easily return the following morning to finish work begun the previous day. Sampson says her creative flow differs from phase to phase of the work. Making tintypes requires planning of subject matter. For example, peanuts.

“I discovered peanuts! I observe and feel them fall through my fingers and land in the bowl. I know when it works because I feel it in my gut. Then I sleep on it and review the following day. I look at my tin type of peanuts and ask, what is right, what is wrong,” she said.

In the way that the Impressionists worked in series of single subject, recording variance—like Monet with his haystacks—Sampson is following the light and how it changes the look and feel of an object. Thus, the peanut study continues!

Sampsons finds collage challenging as her newest practice, and one that requires the most time. It is no wonder to her that she finally dropped into it during the pandemic, and conversely, why it has become the most challenging work to commit to, post-lockdown.

Her collage practice comprises sifting through all manner of photographs and cutting and playing with images. There are the different tools involved; numerous sizes and types of X-Acto knives and scissors, glues, paints, and base papers. Sampson tends to work on several pieces simultaneously to give ample time to the process of assembling, disassembling, and reassembling. She’s not certain she exactly begins with a plan, but if she does, she prefers it to be a subconscious one.

“Once I’ve spent enough time in my collage brain, I think my emotions find their way to my fingers. I’ve noticed that when I allow myself to just ‘go for it’ and commit to something with glue, that can be the moment when I know the piece is complete,” she said.

The arc in Sampson’s work has changed considerably over the last 20 years. The biggest evolution is that she has learned how to push herself in ways she didn’t know she was capable of, and in doing so, discovered that this process has enriched her entire life, both as an artist and as a person.

“I moved around a lot, didn’t want to commit to one thing, but instead said yes to everything to see what would stick. I couldn’t figure out how to make the photographs I wanted to make,” she said.

Relocating from Seattle back to the Bay Area in 2004 was more disruptive than expected, and she felt lost artistically. Around 2006, Sampson began taking classes on methods of photography yet unexplored. Previously having only photographed, processed, and printed black and white film, Sampson became exposed to Polaroid/instant film, color printing, platinum/palladium, and photogravure/copperplate, expanding her creative vocabulary. It wasn’t until she took a wet plate collodion class that she knew that “this was it”, altering her approach in the process.

“Wet plate collodion required that I change camera formats, use a tripod, and make my own chemistry; I would have to be more intentional. No more on-the-fly shooting,” she said.

Eventually, she found her way to her “Skaters” and “Skater Girls” portrait series, and eventually published them in an internationally acclaimed book. The work, and the inherent pressure assigned to the book deal that accompanied it, excited Sampson, forcing her to work in ways she had not before.

“I pulled back from my non-photography job. I was required to engage with strangers in a new way. I loved the challenge and yet struggled with it, didn’t know if I could do it. It could be relatively easy at one moment and then intolerably grueling the next,” she said.

Her creative practice expanded. She was voted in as Board President of the East Bay Photo Collective, formed the Rolls and Tubes Collective, which included a traveling exhibition and book, helped to open up the Oakland Photo Workshop in Oakland’s Chinatown neighborhood, and began writing for media platform WithItGirl, all by the end of 2021.

These days, Sampson continues her “Skater Girls” series, along with tintype series “Passiflora Multiples” and “Oculus,” darkroom silver gelatin prints of photographs taken on weekly walks during the lockdown in 2020-’21. Most recently, “My Weeds”, a series of 10 works on reflective copper plates, has become a new focus.

Recent exhibitions include the Harris/Harvey Gallery in Seattle and the exhibition, “A History of Photography” at the Chung 24 Gallery in San Francisco. Sampson will participate in East Bay Open Studios Fri/1–Sun/3 and the “Pretty in Pink” juried exhibition at Gray Loft Gallery in Oakland from January 13–February 17. Sampson is also slated for a show late next year at Bolinas Museum from November 16–December 31.

Jenny Sampson hopes people will slow down and be inspired to observe their environments with thoughtfulness. She wants to make us laugh or smile and reconsider what we previously supposed about her subjects, whether it inspires or confuses us. And she encourages us to support the arts.

“Galleries and artists often offer payment plans making support possible. And having art on your walls enriches your life!”

For more information, visit jennysampson.com and on Instagram: @jennysampsonphotography, @jennyruth22, and @rolls_and_tubes. Sampson teaches a class on tintype portraiture at the Urban School.