Robin Sloan‘s third novel, Moonbound, released in June, is a fantasy story that takes place in the deep science-fiction future—no fewer than 11,000 years hence. It’s also a story about stories, rich with quests, artificial intelligence, and more than one hero’s journey.

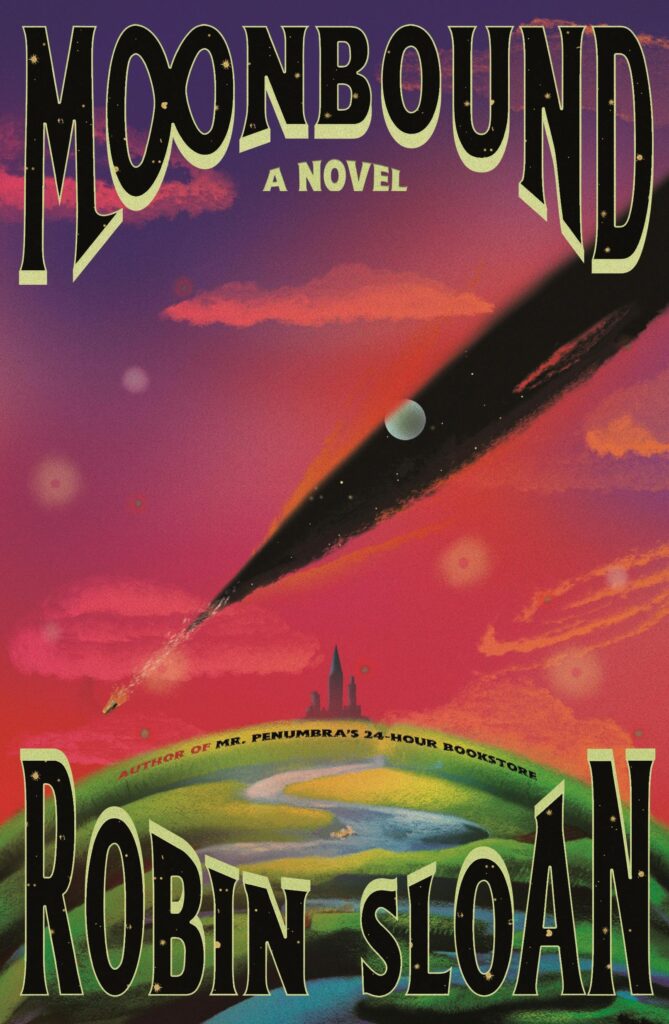

The legend of Arthur looms large, at least until Moonbound’s protagonist, a boy in a realm ruled by a wizard, elects for an alternate path. It unfolds in a future to which the past has sent stories, hoping to reverse the troubling course history has followed. That quandary manifests as yet another story, about dragons on the moon, that has plunged what remains of humanity into fear. The novel builds on themes, such as powerful tomes and sentient fungi, from Sloan’s previous novels—his debut, the New York Times bestseller Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore, and Sourdough are both set in the Bay Area—such that Moonbound’s cover announces it as the latest in the “Penumbraverse.”

Sloan, an Oakland resident, is a prominent presence in San Francisco literary life, often interviewing authors coming through town on the trade winds of their latest publications. Wired recently named him “the tech world’s greatest living novelist.” He spoke with 48 Hills via what old-school scifi called a “video phone,” aka Zoom. As the conversation began, Sloan pointed over his shoulder to the ancient Risograph printer on which he printed the nifty zine he snail-mailed to people who pre-ordered Moonbound.

We proceeded to talk about, among other topics: uninformed protagonists, the technologies of narrative, and San Francisco’s double-helix bond with the future. The following has been edited for clarity and length.

48 HILLS I saw you read at a recent SF in SF event with your fellow novelists Rudy Rucker and Clara Ward. While Rucker spoke, you stroked Moonbound‘s cover, which features embossed elements. From the book’s glyphs to its opening map, not to mention your Risograph zine, it’s clear you’re into the book as an object. Could you talk a bit about that physicality?

ROBIN SLOAN While I always identified as someone who likes books, I did not really understand the potential for expression in that object until I linked up with my longtime publisher, FSG, for all three novels, in particular my editor, Sean McDonald. I dunno if he’s ever said this, but I’ll just paraphrase his vibe: in the 21st century, if you are going to make a print book, you’ve got to make it worth people’s time. This started with my first novel, Mr. Penumbra’s 24-Hour Bookstore. They showed me some sketches for the cover and said, “Wherever you see that really bright yellow color, that’ll glow in the dark.” And I was like, “I didn’t know that was an option.” From that point onward, there’s been a real sense of play. The domain of the digital has grown and grown, which has made it feel more urgent to spend time on physical artifacts.

48 HILLS Moonbound reveals that beavers communicate through the structures they build, so the idea of physical objects expressing meaning is right there in your story, right?

ROBIN SLOAN I often think of the eloquence of the physical, and that takes a lot of different forms, but one of them germane to this discussion. A digital book, an article that you’re reading on the 48 Hills website, any kind of ebook you buy on your Kindle—they all have the same property: They go quietly into the night as soon as they scroll off that page. It’s still there, but you’ve got to go dig for it, and often you don’t. You just forget it’s there because something else has replaced it in the infinite feed. A physical book is stubbornly asserting its existence. It sounds simple, almost glib, but that physical object, the physical book, can do that: can sit on a shelf or on your desk and go, “Hey, remember me?” That is powerful, now more than ever.

48 HILLS: Moonbound’s narrator is an AI called a “chronicler” that embeds itself into the consciousness of other characters. The AI has its own perspective, plus a vast database of history, all while folding in information from the persons it’s been biologically bound to. How did that narrative device come to be?

ROBIN SLOAN I’m sincerely glad to hear people report it works. I was confident but I wasn’t a hundred percent sure. Technically, in craft terms, that is the part of the book I’m the proudest of. It took tinkering and development to get there. In a way, it was me solving a problem I’d identified for myself. My previous two novels were written in the first person. I’ve always loved that, as a writer and a reader. The opportunities for humor are greater if you have a strong point of view. However, over time, I became more aware of the limitations. I think it becomes more severe in a fantastical or science fictional mode because it’s annoying to be stuck with a character who doesn’t know anything. You get tired of “Wow, what’s that?” “Whoa, what are they doing?” It’s like, come on, somebody’s got to know something. It turns out in fiction, it is fun when people know things and have opinions about them.

48 HILLS A big part of Mr. Penumbra is that the main character doesn’t know anything. That format works well because he’s an intelligent character, but almost everyone else in the book knows more than the narrator does.

ROBIN SLOAN: Yeah, and that book was only medium weird. There are obviously other options. It is my opinion that the full-on third person, the old-fashioned omniscient narrator, is hard to do intellectually slash politically in the 21st century. It’s fun but there’s no escaping this question of who the hell is this supposed to be?

And it’s fun that the chronicler is “diegetic,” you could say: It’s not just literary technology; it’s actually science-fictional technology. It’s an approach that arose out of the story, which also gave me these literary tools. It’s an embodied first person, with opinions and a point of view. It’s also that classic limited third person narrator on the character’s shoulder. And it’s the encyclopedia, a touch of omniscience, because even if the chronicler doesn’t know everything about the world they’re in, it knows about the universe and what’s possible. I felt like I had a problem to solve, and I’m really happy with the solution that I found my way to.

48 HILLS Though I haven’t counted, I’d say there may be more semicolons in Moonbound than in your previous two novels combined. There are traditional semicolons, like where two sentences connect for reasons that people who don’t like semicolons can’t really deal with. But a lot of times in the book, semicolons are doing their own thing. Can you talk about your semicolon journey?

ROBIN SLOAN: I’ve gotten more confident with punctuation. I used to sweat it, worrying about—air quotes—proper usage. Maybe it’s all the writing I’ve done online. Sending long newsletters has been training. You try different things. I am totally comfortable with almost arbitrary deployment of not only semicolons, but colons and em-dashes. I love that I don’t know if I could articulate my own theory of usage, but it’s not arbitrary.

The thing that I think is the most unhinged that I do—and that therefore I like the most—is the double colon. Usually you are, like: phrase, colon, thing that explains that phrase. But sometimes it’s not enough. So you go: phrase colon phrase another colon: To me it feels right. If I had to write down the algorithmic rules for it, I couldn’t. It’s locked up in the aesthetic matrix of my brain. But I cannot be stopped. This is great to remember: the opportunity still and always exists to invent new usages. It’s freaking awesome.

48 HILLS: This is a question you’ve been asked variations of since the book came out, and I need to ask a variation of it myself. In Mr. Penumbra, the Google employee, Kat, talks about the difficulty of imagining the far future. She estimates: “We run out of analogies in the thirty-first century.” Yet you pushed ahead 11,000-plus years. How hard was it?

ROBIN SLOAN: It was difficult. And it goes to show it has been a preoccupation of mine. That begins, I think, as a science fiction reader myself. Truly credit goes to the San Francisco–based Long Now Foundation, which has been a meaningful input. Like the mid-2000s for me, especially, hearing geologists kind of just dance across time, millions of years—it was truly formative stuff. That tees up the interest. But then, yeah, how do you do it? And for me, it is like it’s pushing in from both sides. On one side, you want to rise to the challenge. You want to push beyond the sort of “near future”: Yes, it’s now, except everyone wears a trench coat and it’s raining all the time. Which is fun. I love it.

But you’re like, let me go further and weirder, and what does that mean? For instance, anybody who thinks about that for more than two seconds realizes it’s got to take seriously the non-human, right. It can’t just be the future of humans because that’s not the full future at those timescales. So that’s pushing from one direction. There is a counterforce, though, from the other direction: the demands of being able to tell a story at all. It would be cool and interesting to write a book about Earth 20 million years from now, but you actually couldn’t without time travel.

48 HILLS: Did your imagination hit walls you had to push through?

ROBIN SLOAN: The word “wall” doesn’t seem right. To have fun with analogies, I think it was more of a hike through a landscape—at certain points, surmounting ridge lines and seeing these broad vistas.

48 HILLS: San Francisco plays a big role in Moonbound, if not as central a role as in Mr. Penumbra and Sourdough. That far into the future, how did you find your way to San Francisco—which in the book you describe as “the city the future reached back and made, because it was going to be needed.”

ROBIN SLOAN: It absolutely had to. A broader engagement here with the future is just—you have to really ignore all the people around you in San Francisco not to have that seep in. That’s been a powerful influence on me. I took a great note from Kim Stanley Robinson’s novel The Ministry for the Future, which I loved. In setting up a scene, he writes, “San Francisco, the most beautiful city in the world.” He’s not trying to convince you. He’s just telling you; it’s like “carbon, the sixth element.” I freaking loved that. I thought it was such a fun move. So I literally do the same thing. There’s a line where a character named Durga says, “San Francisco, the most beautiful city in the world.”

48 HILLS: When I reread Mr. Penumbra recently, I was struck by its admiring tone regarding Google. It’s complicated to reread. While the approach doesn’t hold up to what happened in reality, it’s a beautiful amber capsule of an outdated perspective.

ROBIN SLOAN: I have come to think of it as a useful time capsule. I hope somebody writes a PhD thesis in another 20 years, like “Textual Evidence for the Changing Perceptions of Tech Mega Corporations.”

48 HILLS: Along those lines, I appreciated how you wrote in Moonbound about San Francisco bereft of the hate aimed at this area by people who’ve often never even been here.

ROBIN SLOAN: I think this is San Francisco’s burden, but also its gift: it’s not just a place; it’s a symbol and a weird beacon. I always remind myself that the complaints and horror stories about San Francisco are not about a real city where real people live their daily lives, because the people making these arguments don’t want them to be.

Who knows what the future holds for San Francisco, or for the Bay Area, but if the past is any indication—I mean, it’s that protean rise and ruin, rise and ruin, the giant pistons in this engine: an economic engine, a cultural engine, an aesthetic engine. That’s what it’s always been, and what it’s always going to be. You can’t have the rise without the fall. But I will say I’m among the top rank of the world’s great San Francisco evangelists. I sometimes say San Francisco “patriots.” I’m a believer to my core.