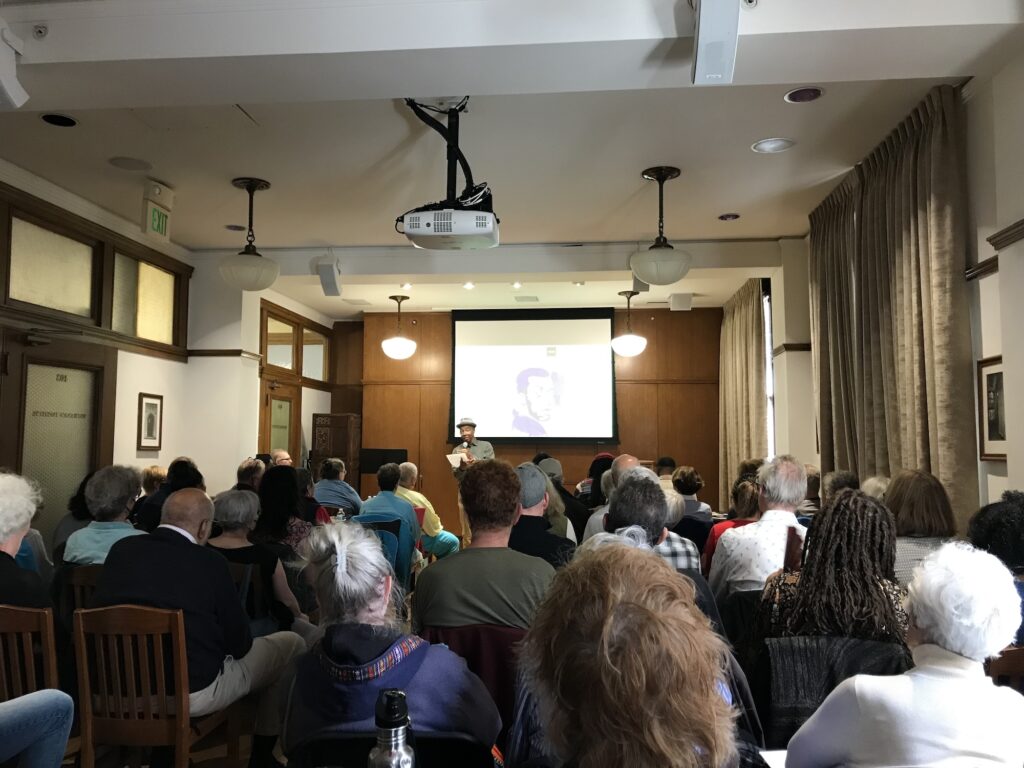

Last Friday, more than 100 fans crowded the Mechanics’ Institute Library to celebrate James Baldwin’s 100th birthday, honoring his legacy through music, art, and literature. Titled “In His Own Words: A James Baldwin Centennial Celebration” and co-presented by the Museum of the African Diaspora, the event featured dedicated scholars reading from his masterpieces.

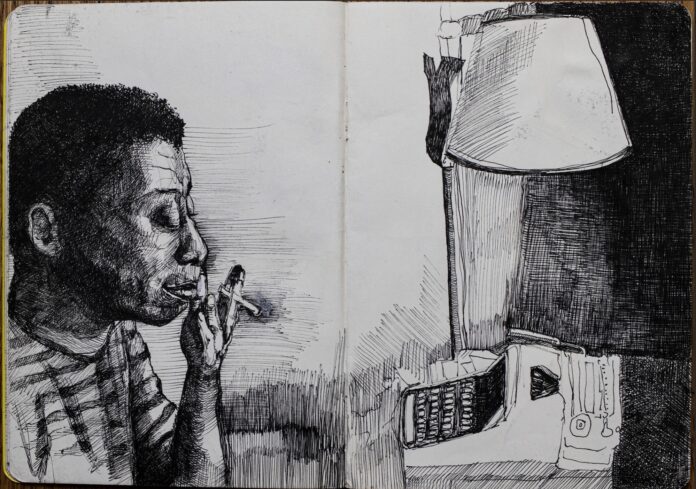

“In His Own Words” began with the happy thumps of “I Heard It Through the Grapevine,” then segued to the outraged riffs of “Mississippi Goddam” as “Frontline Prophet: James Baldwin,” a traveling slideshow exhibition that features the work of Detroit-based artist Sabrina Nelson, dazzled the audience with images of the artist of whom Toni Morrison said, “no one possessed or inhabited language…..the way you did” at his eulogy in 1987.

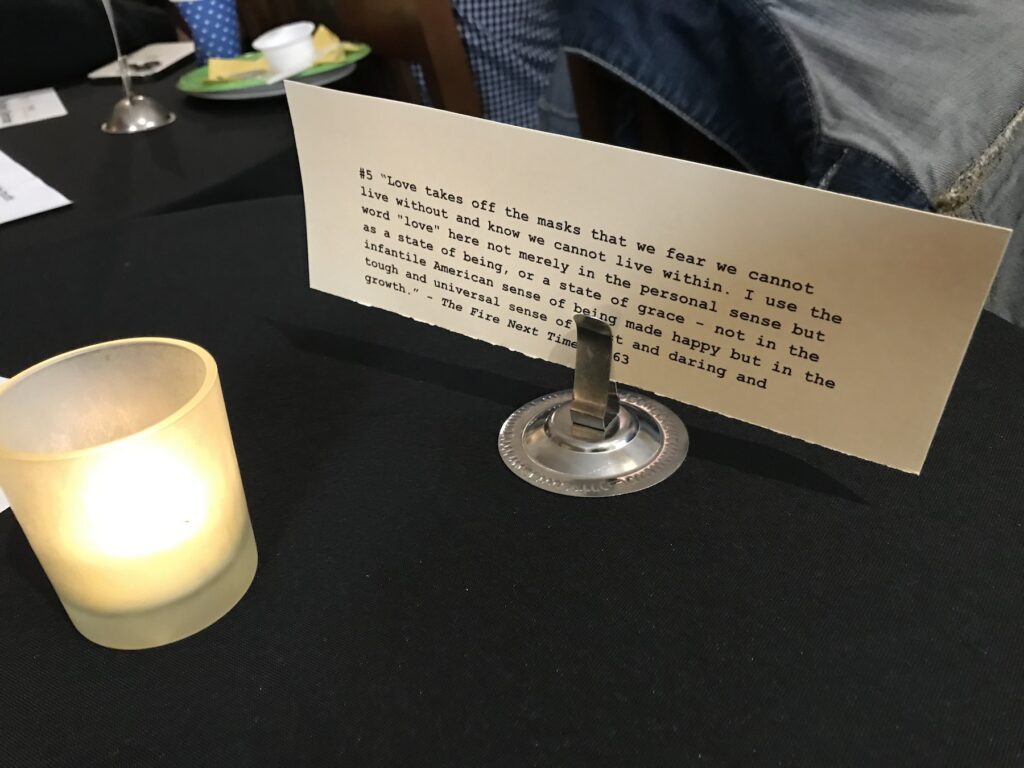

Audience members were invited to read Baldwin quotes from candlelit tables, every quote a reminder of how hard it was to be a lover of language and not a lover of James Baldwin.

“You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read” was a good starting quote, in a San Francisco library that’s been around since 1854, and featured a table from Revolution Books. “It was books that taught me that the things that tormented me most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who had ever been alive.”

Norman Gee, executive director of the Baldwin Centennial Project, opened the homage with an excerpt of Notes of a Native Son, reading a monologue that he would perform later that night on San Francisco’s Potrero Stage.

“How can we start the celebration of his centennial,” Gee asked. “Let’s start with his own words: ‘Not everything that is changed can be faced, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.’”

Gee noted that at the height of Baldwin’s notoriety in the 1960s, he was everywhere, in magazines and marches and talk shows, college campuses and even local high schools in the Bay Area. The 2020 documentary I Am Not Your Negro reviralized his famous retort to economics professor Paul Weiss on the Dick Cavatt show in 1968, a takedown of all the institutions that serve white society but ignore—if not outright persecute—people of color.

“And yet until the end, he never gave up hope,” Gee said. ‘We are responsible for the world in which we find ourselves, if only because we are the only sentient force which can change it.’”

Daniel B Summerhill, whose essay “Praying for Rain” converses with James Baldwin’s legacy, pauses after taking the podium to praise the mesmerizing “Frontline Prophet” slideshow.

“So fire,” Summerhill said. “The artists have paid attention to those pronounced, bulging eyes. His eyes remind me of my son when he first opened his eyes.”

“I imagine we’re all here because we want to honor James Baldwin today,” Summerhill said. “I want to say thank you to Uncle Jim, for teaching me how to be a human and a writer and a father, even though he never had children.”

Summerhill read from, appropriately, “A Letter to My Nephew,” first published in The Progressive magazine in 1962 on the one-hundred year anniversary of emancipation. Testimony to Baldwin’s genius as an essayist to transform his personal angst into a public cause, the private letter is a public howl on the “crux of my dispute” with his country.

“You were not expected to aspire to excellence,” Baldwin warned his 15-year old nephew. “You were expected to make peace with mediocrity.”

Baldwin, the ultimate outsider-outsider as a gay Black expat who spent much of his life in Paris, had every reason to be bitter, yet always returned to love. For the critics who felt he erred toward anger, Baldwin countered that both love and anger were necessary.

“The really terrible thing, old buddy, is that you must accept them, and I mean that very seriously,” Baldwin told his nephew. “You must accept them and accept them with love, for these innocent people have no other hope. They are in effect still trapped in a history which they do not understand and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it.”

Novelist, poet and playwright Jewelle Gomez upholds the theme of Baldwin’s deep conviction to loving individuals in a world where institutions hate them by reading from his 1972 book, No Name in the Street.

“Love was the key to life. Because if you love one human being, you see everyone else differently.”

Educator and economic justice advocate Kevin Dublin noted the power of Baldwin’s voice, as “something that just vibrates.” He read excerpts from Baldwin’s essay “Nothing Personal,” first published in 1964, then re-released in 2017 with photography by Richard Avedon.

“We have all heard the bit about what a pity it was that Plymouth Rock didn’t land on the Pilgrims instead of the other way around,” Baldwin wrote, somehow anticipating the nervous laughter in the room, even from his grave. “I have never found this remark very funny. It seems wistful and vindictive to me.”

Baldwin never allowed his mind—or his audience’s—to rest in smug certainty. But he was consistent in letting love get the last word, even when he conceded that “Love has never been a popular movement.”

Dr. Nigel Hatton, Associate Professor of Literature and Philosophy at UC Merced who will lead a 12-session seminar on Baldwin beginning August 27, closes the night by drawing attention to Baldwin’s fiction, how fiction confronts us through the form’s ability to read its audience.

“Joyce Carol Oates called Baldwin the greatest essayist of the 20th century,” Hatton said. “But in an interview Baldwin said, ‘Well, of course, people like my essays. Essays are easy to read. And nobody wants to be a racist.’ But what he added was, it’s difficult to be a person. Baldwin wants us to wrestle and wants us to struggle.”

Hatton reads from Baldwin’s 1968 novel Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone, which opens with protagonist Leo Proudhammer recovering from a heart attack with thoughts that echo Baldwin’s demands about love from his essays.

“Now, for the first time, I began to be aware of my heart, the heart itself. And with this awareness, conscious terror came. I realized that I knew nothing whatever about the way we are put together; and I realized that what I did not know might be in the process of killing me.”

The evening ends as any evening with Baldwin should, with more to say, think, and feel. Even Toni Morrison felt both comforted and challenged by Baldwin to the very end.

“You knew, didn’t you, how I needed your language and the mind that formed it?” Morrison closed her 1987 eulogy to Baldwin. “How I relied on your fierce courage to tame wildernesses for me? How strengthened I was by the certainty that came from knowing you would never hurt me?”

“You knew, didn’t you, how I loved your love? You knew. This then is no calamity. No. This is jubilee. ‘Our crown,’ you said, ‘has already been bought and paid for. All we have to do,’ you said, ‘is wear it.'”