A real-estate investor with a history of attempting to evict vulnerable low-income seniors in Chinatown is now in the middle of a controversy over the future of a historic banquet hall and building that could have larger implications for the future of land use in the neighborhood.

John Yee, who owns the 838 Grant St. building where the Empress of China restaurant used to operate, wants to turn the top floor into a high-end dining space.

That, the Chron reports, has community leaders worried that the space will no longer serve local residents and businesses and will instead cater to rich tourists who will drop in for a pricey meal and then leave.

As Malcolm Yeung, deputy director of the Chinatown Community Development Center, told me, “the patrons will Uber in, pay for a fancy meal with their American Express Black Cards, and Uber out. They won’t be patronizing any other small businesses in Chinatown.”

There’s a bigger story here: What community leaders fear Yee wants to do is turn the lower floors of the historic structure into high-end office space – rented at rates comparable to the Financial District – and set a precedent for tech-office creep into a neighborhood that has fought for decades to protect its cultural identity and traditions.

In fact, the threat both to cultural space and community-serving businesses has brought the diverse groups in Chinatown – not all of whom always agree on political issues – together.

“We have an incredibly united community on this,” Yeung told me.

Chinatown cultural institutions are looking for affordable space. Family associations, nonprofits, and people who use banquet halls for weddings and other celebrations are looking for affordable space.

There’s so much interest in preserving the building that a broad-based coalition has approached Yee about buying the building.

But that’s not going well.

Yee paid $17.2 million for the property in 2016, according to records on file with the Assessor-Recorder’s Office. According to records on file with the Planning Department and Department of Building Inspection, he has spent $848,000 on renovations and upgrades.

Yeung has met with Yee twice to discuss a community-based purchase. “You are going to laugh when you hear this,” Yeung told me. “The price he wanted for the building is $54 million.”

That, for the record, is triple what he paid for the building and has put into renovating it.

My attempts to reach Yee were unsuccessful, but he told the Chron that he is committed to Chinatown:

Building owner John Yee, an immigrant who grew up in Chinatown and purchased the Grant Avenue site for a reported $17.2 million in 2017, said he is committed to contributing to the community. His goal is for the building’s businesses, including Empress by Boon, to be “authentic to the cultural identity of the neighborhood,” he wrote in an emailed statement.

(Memo to Chron: The sale price of a building in SF is public record, and easily accessible.)

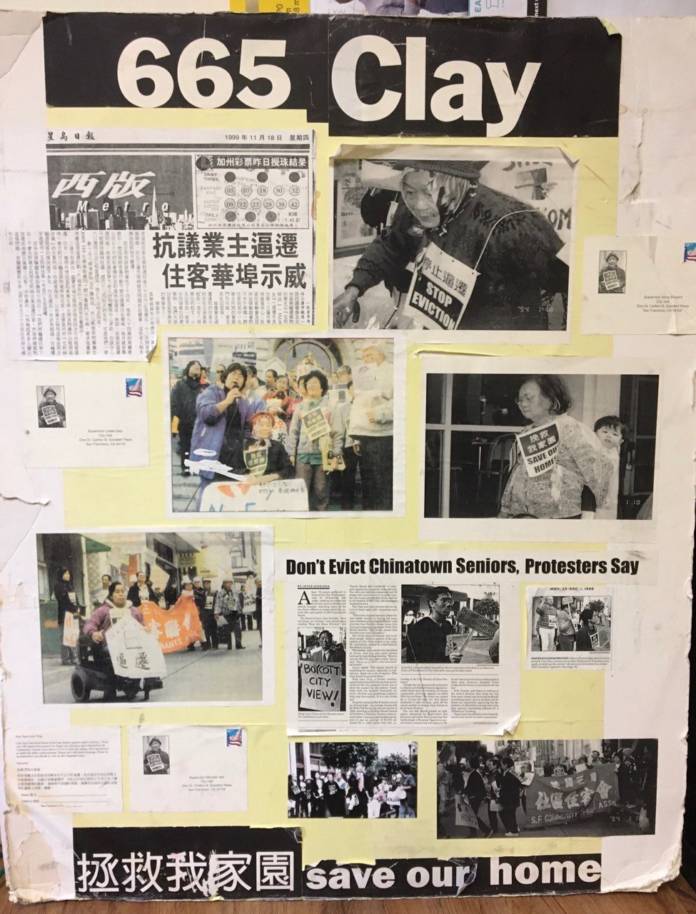

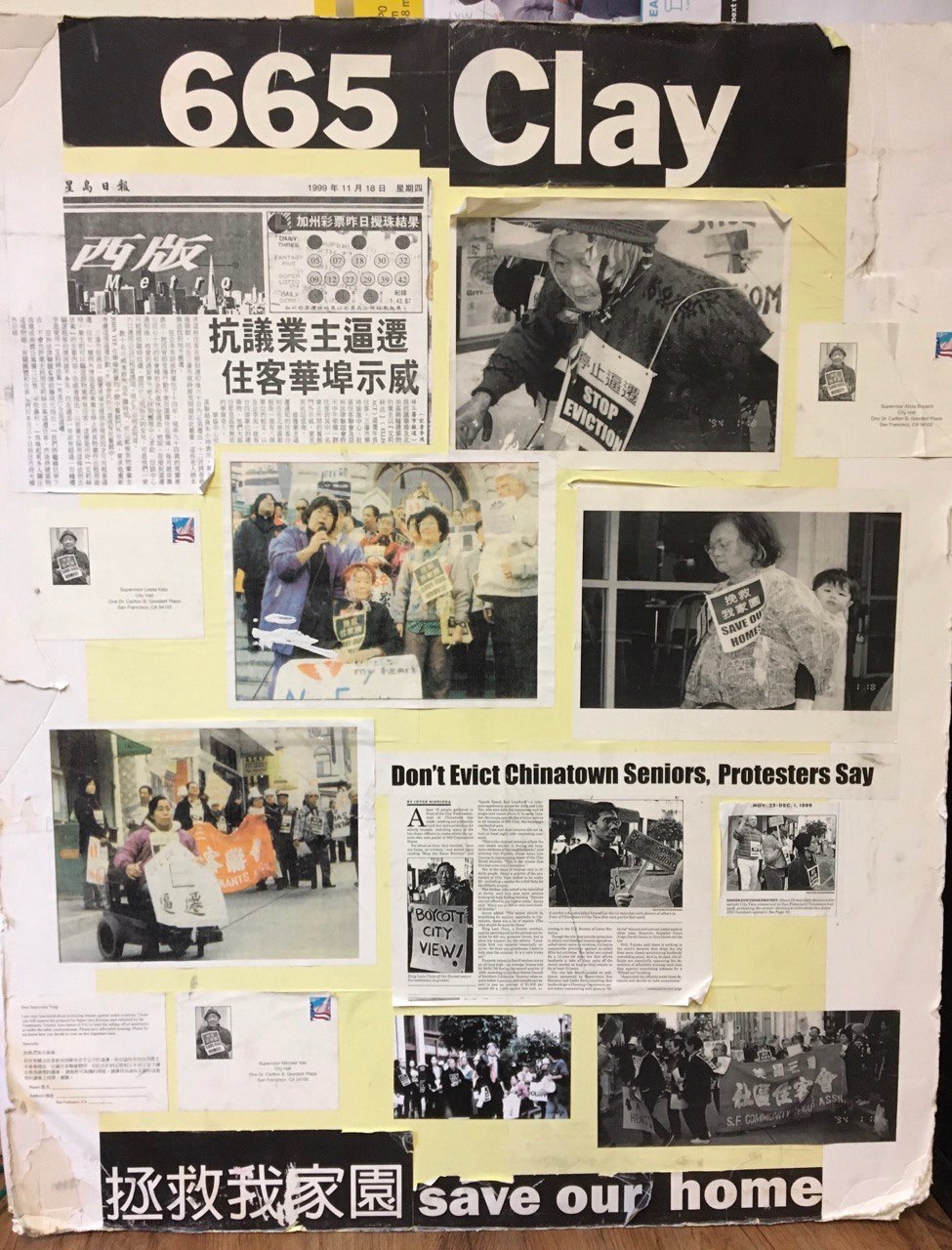

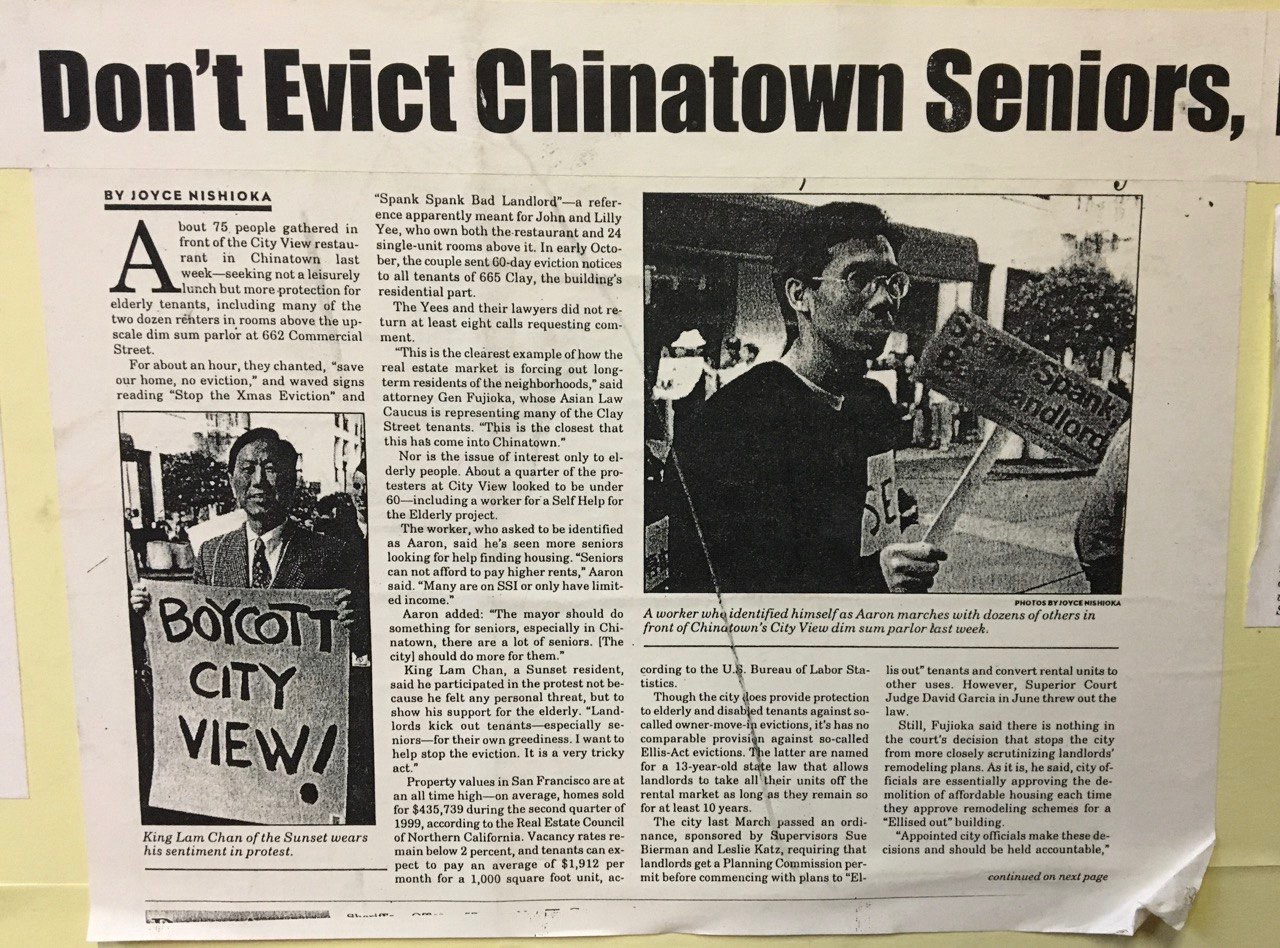

Yee was part of a notorious effort to evict the tenants of a residential hotel that he bought in in 1994.

In 1999, he filed an Ellis Act eviction for all of the residents of 665 Clay, including a 95-year-old who had no other place to go.

The evictions only were halted when Yee agreed to sell the building to CCDC– at a handsome profit to himself.

Chinatown has very specific zoning rules, that seek to keep space for community-serving businesses. The offices in the Empress of China Building are limited to professionals like lawyers, health-care practitioners, and accountants and whose clients are primarily neighborhood residents.

None of those tenants could afford the rent levels that tech and big corporate offices pay in the financial district.

“The numbers that he is talking about are somewhere between downtown and the Transbay Terminal district,” Yeung said.

Yeung has filed an appeal of Yee’s restaurant permit, but that’s limited to the question of whether there might be an affordable way to preserve banquet space in the neighborhood.

The larger issue is whether a landmark building will become a foothold for real-estate speculation that would amount to a major threat to the future of Chinatown.