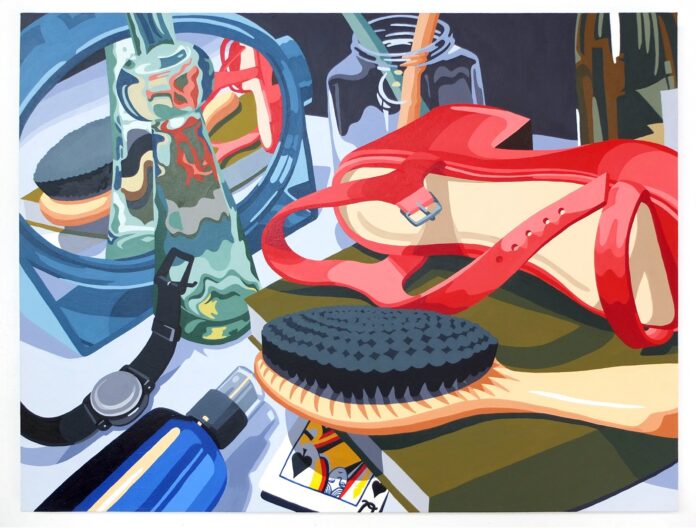

With both paint and clay, artist Annie Duncan evokes nostalgia in everyday feminine objects. A tube of lipstick, a hair clip, a perfume bottle, all stir up emotion within the context of the familiar and the symbolic in our lives. With humor and poignancy, Duncan plumbs how these intimate objects, often way oversized in scale, can conjure a particular joyful—or heartbreaking—moment.

Duncan grew up in San Francisco, in a small apartment on the fourth floor of an old, brown-shingled Victorian on Maple Street. The sunlight that poured into the space always made it feel like an enchanted space to her.

“I remember if I stood on the bed in my parents’ room and looked out the top window, I could see the ocean,” Duncan told 48hills.

Duncan returned to the Bay Area after living on the East Coast for a handful of years, where she attended Vassar College (BA, 2019) and says that move back felt like an incredible homecoming. The sunlight, the plants, the smells, the fog—it all felt so right to the artist. With the arrival of the pandemic in her mid-twenties, she had a real moment to pause, slow down, and assess what she wanted out of life. Duncan received her MFA in 2023 from California College of the Arts. Changes to the city in her absence, its distinct character and texture when she was growing up, were not lost on her, and she notes the old-school business that have disappeared.

“But it’s still so beautiful—the light, the colors of the houses—and the magic is still in this city. Any artist who is still here, despite everything, is here because they can feel it,” Duncan said.

Currently living on Fillmore Street in the downstairs, in-law unit of her parents’ house, Duncan can afford renting an art studio. What she enjoys most about being here is the small, special art community and uplifting feeling of collective support, how she is always running into familiar people, in addition to meeting new artists and curators.

“Right now, in this moment, it feels like there is a ton of momentum—new spaces opening, events—a really fresh energy. The ceramics community, in particular, is so strong in the Bay. There’s a rich legacy of clay here, and some remarkable artists, many of whom I’ve gotten to work with or meet,” Duncan said.

Her main sources of inspiration come from two distinct camps. One is the abundant world of art historical references that she plays with: object symbolism, still life conventions, and painting traditions. Another is the texture of the contemporary world we inhabit, filled with our intimate objects.

“A lot of my work looks closely at objects that are in some way connected to ideas of femininity—beauty products, accessories—but also symbols that have been used in reference to the female body like shells, flowers, and fruit,” she said.

Recently, she’s also been finding inspiration in the natural world, in addition to the domestic spaces she usually references. Taking long walks around the Mission District near her studio, Duncan has discovered stunning back alleys that are overgrown with flowers breaking through sidewalks and cascading down telephone poles. She has become obsessed with the juxtaposition of the natural-urban ecotone.

“Particular flowers around the city are also of interest to me, like devil’s trumpet, which are everywhere in San Francisco. I’ve started a series of sculptures that reference the form of this hanging flower. I love that the city contains something so beautiful, but also incredibly poisonous,” Duncan said.

This feeds her recent curiosity towards objects in general that contain some kind of contradiction or duality, saying it feels allegorical to our true natures, to be both beautiful and toxic simultaneously.

In her practice overall, Duncan always leads with instinct, then circles back to resolve what she is addressing. It’s important for her to honor that first instinct to create. Last year, Duncan began obsessively making a series of supersized, jumbo hair clips in clay. Feeling drawn to the form as a feminine-yet-aggressive object with its spiky arms, as she began to scale them up, she realized that the form was also a reference to the spider sculptures of Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010).

“I like thinking of the claw clips as part of this conversation—anthropomorphized objects that have a real presence, conjuring the feminine and the absurd, while their oversized scale gives the object a new character,” she said.

Approaching her work with a sense of playfulness within an exploration of color and symbolism, Duncan alternates between painting and works in clay. Which medium she chooses on a given day is determined primarily by mood.

“Sometimes I go to the studio and I know I want to work with clay, to do something really physical. Other days I feel more like mixing colors,” she said.

She cycles to her studio, which is located off Valencia Street around the corner from Arizmendi Bakery. Duncan notes the street’s new bike lane changed “everything” for her. She arrives at the space, which she found through Craigslist and is situated on the bottom floor of an old Victorian. With a sunny courtyard, there is lovely light throughout the space, especially in the fall and winter. Duncan begins around 10am and works until 7 or 8 in the evening.

“It’s a cozy little space, and even when it gets cramped, it feels like my sanctuary. I was really excited to find a space that has its own door, windows, and ceiling. I like to play my music off the speaker and not use headphones—it’s a true luxury. The location is fantastic and for now it feels like the right spot,” she said.

Duncan also frequently listens to audio books as she works, plowing through up to three books in a week. She says connecting to novels and short stories feels fitting, as her own work is about storytelling and world building.

It took Duncan a moment to finally arrive at being an artist. For many years, she was interested in design and was certain her path was architecture or graphic design. Her father is an architect, and Duncan grew up immersed in that culture, always drawing and building houses or furniture for dolls, but also sewing, and working in clay early on.

“When I finally gave myself permission to say, ‘I want to be an artist’, it felt so right, so natural. I didn’t get seriously involved with clay until graduate school, coming in as a painter,” she said.

But as soon as she learned how to build big with clay, a new world was unlocked. Ceramics felt like a natural extension of her practice. The form brought a new physicality to the subjects she was interested in, particularly objects that related to the body in some way. Objects that had appeared in her canvases—an IUD, pink plastic razors—could now take on a stronger physical presence. Teasing out the relationship between the two mediums, Duncan overlaps ideas from painting into her ceramics works, treating the glaze and the object in the same way that she would a canvas, brushing shadows and light.

Duncan believes there is power and subversiveness in making work that’s accessible to people on multiple levels, and has been surprised by reactions from people to her work—particularly, how delighted or vulnerable seeing intimate objects at such a tremendous scale makes them feel.

“Some people have become quite emotional talking to me about my work, and I never expected it to speak to people that way, but it seems like it raises so many personal stories and connections,” she said.

Duncan is working on a new series of hanging flower lamps, incorporating electric wiring and light, and is incredibly excited about the installation possibilities. She is also revitalizing her drawing practice.

“I do one [drawing] in the morning and one in the evening. At the end of the day, all comes back to drawing,” she said.

Annie Duncan hopes that people will feel an affinity for her work and experience joy, surprise, and resonance. She intuits the importance of multiple points of entry. Watching viewer’s recognition and engagement with the work, especially children, and the shared familiarity with everyday objects is important to her.

“There’s so much significance and energy in these objects, and everyone has such a unique relationship to them—the rituals and performance connected to them, the nostalgia, too. Unlocking that relationship, I never know quite what it will bring up for others. I know what it means to me, but it gets interesting when other people bring their experiences to it,” Duncan said.

She has exhibited work on both coasts, and in December, Duncan’s work was shown by Johansson Projects at last year’s Untitled Art Fair, which took on the theme of “gender equality in the arts.” Her solo exhibition “Tremble Like a Flower” opens at Johansson Projects’ Oakland space on Fri/5, and runs through February 17.

“I feel so incredibly lucky to be a practicing artist and to feel the amount of support that I do here in the Bay Area,” Duncan said. “What a generous and warm place this is. It’s such a gift to go to the studio and not know what I’ll make—to be able to surprise myself. I’ll never get tired of it.”

For more information, visit her website at annieduncan.com and on Instagram.