At news of the killings in Paris, the Bay Area’s cartoonist community proves the pen is mightier than the Kalashnikov.

By Marke B.

January 12, 2015 — This past Friday at noon a small, determined group of California College of the Arts faculty and students gathered in the back lot of the CCA campus with a firm purpose. They were there for an impromptu cartooning session — to pay tribute to fellow artists and staff at Charlie Hebdo who had been massacred two days before, and to celebrate the values of free expression which they felt had been directly attacked.

“This wasn’t about personal catharsis, although of course we took strength in each other’s presence,” Director of CCA’s Graduate Design Program Leslie Roberts, who had called the session, told me afterwards. “It was about doing our necessary duty as informed citizens in a civil society: to speak out fully and concretely in a time of crisis, in the best way that we know how. It was also a reminder that what we do as artists, cartoonists, and designers is a courageous and necessary act. Everyone, everywhere across the entire planet should be able to speak freely, without fear of violence.”

“Speaking concretely” took on actual form in the huge drawing the group produced on the parking lot: a colorful, gridded “Je Suis Charlie” visible from the 280. School has yet to return to session, and Roberts — who had just come back from a holiday trip to Paris when she heard the news — says this is the first in a series of cartooning sessions. “At CCA, one of the main things we aim to do is help students make art that matters,” Roberts told me. “Continuing and sharing the strength that the French people are showing in the face of this tragedy ties into that in a very big way.”

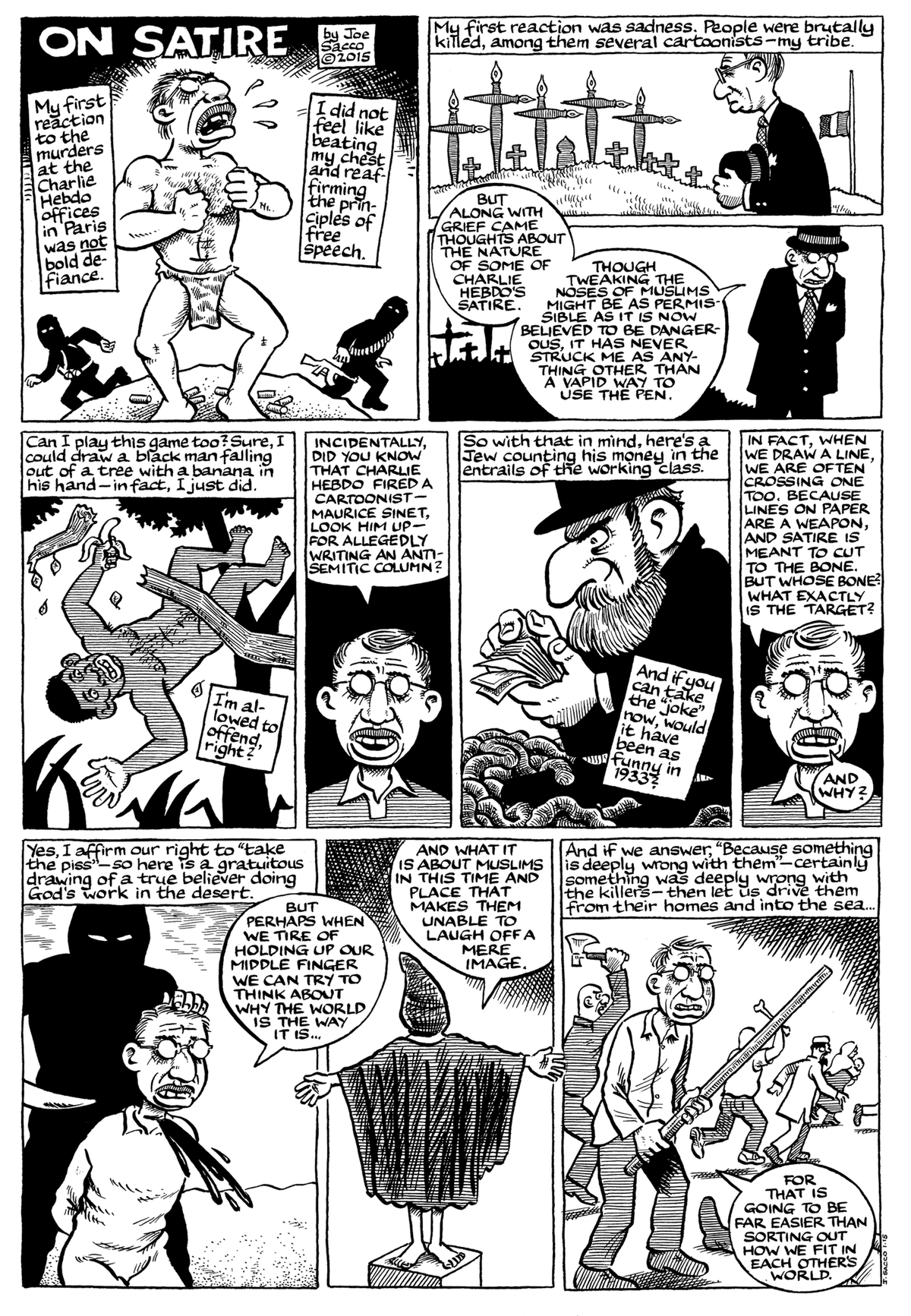

As the shock waves of the massacre hit the international comics community — and valuable debate about the international community’s response began to appear — cartoonists and artists in the Bay Area (the epicenter of the underground comix movement) were quick to react. Some turned to words, including Oakland-based graphic novelist Samuel Sattin, who took the chance to recommend other relevant graphic works, in an essay in Salon. Others, like San Francisco-based artist Bex Freund, were spurred into drawing action.

“My immediate reaction [to the Charlie Hebdo news] was simmering anger, and it only continued to intensify as the information sank in,” Freund told me over email. “While I was cooking myself breakfast, my mind was already busy with mental drawings, and as soon as I was finished eating, I swept everything off my table and started working. I had not drawn a political cartoon in over a decade and a half.

“Normally, I feel emotional distance from most communities or groups that I am a part of, such as the Deaf or LGBTQ communities. So in this instance, I was surprised at my own initial furious reaction. There’s something deeply and unexpectedly tribal about cartooning, and it was like a gut punch to me. I felt as though the gunmen had personally attacked ‘my own,’ and that’s very unusual and new for me. I spent the day unpacking my feelings, reading reams of articles and discussion about Charlie Hebdo, examining my own evolving opinions and perspective. There are so many layers to this. But the anger I poured into my image still rings true.”

Besides being a comics epicenter, the Bay Area is also home to CCA’s groundbreaking MFA Program in Comics. I spoke with the director of that program, Matthew Silady, about how he

“For those not familiar with their work, images produced for Charlie Hebdo magazine might be a bit of a shock: purposely offensive, often blasphemous, and sometimes racist in their content,” Silady told me over email. “The cartoonists killed never shied away from criticism. They welcomed it. Comics is a particularly powerful medium. There’s something about a comic that provokes in a way fundamentally different than words alone. Satirical cartoonists accept the fact that they will be criticized for their work. Anytime we open ourselves to criticism of our art and its message, it’s a courageous act. But murder isn’t criticism. Violence has absolutely no place in the dialogue between artist and audience in any circumstance.”

I asked him if he saw any moments in Bay Area comics history that equaled the scalding satire of Charlie Hebdo.

“At the height of the underground comix movement of the 1960s, the incredible explosion of creative work coming out of San Francisco was at times as caustic as anything being produced today. The misogyny found in some of Robert Crumb’s work, for example, is difficult to look at in any light. But allowing room for artists to explore dark, obscene, or even purposely hurtful subject matter in their work is an essential part of preserving our right to free expression. Even with the best intentions, I’m sure I’ve offended someone with my work along the way. That’s the nature of taking chances and being true to yourself as an artist.

Will Silady incorporate the massacre — and the deep history of attacks against cartoonists, including the 2006 Jyllands-Posten “Danish Muhammed cartoons” incident — into his graduate comics curriculum?

“I’ve touched on past international incidents and threats against cartoonists when I introduce students to the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund (which fights for first amendment rights here in the US). But we probably don’t cover enough. There’s a surprising wealth of censorship issues here at home though. We’re fighting right now to maintain access to LGBTQ themed graphic novels in certain parts of the country, for example. Fortunately, there are some in the comics press such as Tom Spurgeon at the Comics Reporter who really stay on these international stories from beginning to end.”

Special thanks to local cartoonist Justin Hall for help with this article.