May 2 marks the 10-year anniversary of the passing of poet Al Robles. Al Robles was conferred much respect as a poverty scholar of POOR Magazine and remains an ancestor board member of the POOR Magazine family.

Robles’ life was centered on the notion, the struggle to “take back our lives”—our histories, languages, art, land—all of the things whose legacies live in our skin, our blood, all of which have been stolen or commodified/co-opted.

One of POOR Magazine’s mottos is “nothing about us without us.” Robles dedicated his life to telling the stories of Filipino-American elders who were forcibly evicted from San Francisco’s Manilatown neighborhood. This removal was fueled by real estate speculation, the same force that evicts elders and families today—such as Iris Canada, a 100-year-old black elder in the Fillmore—locked out of her home while at a senior meal program.

Therein lies the situation—voices, experiences, histories/herstories, lived experience—locked out, becoming, through foundation grants, endowments, scholarships etc., a project or case study for an academic or some other with degrees and privilege to write about, take pictures of, document etc.

Al Robles himself was steeped in academia for a time. The poet/historian attended USF, a Jesuit university and was introduced to the philosophies of Thomas Merton, among others. However, the neighborhood that produced him, the city’s Fillmore, was close and the sounds of jazz, the struggles of the black and brown and yellow people of the neighborhood—the mixture of sounds from tongues stained with soy sauce, hot sauce, vinegar, picked pig’s feet—would not allow him to forget or fall to what POOR Magazine calls the cult of separation or independence.

He couldn’t forget the voices, the sounds of the workers, the voices from the fields where the seeds of Manilatowns across the US were planted long ago. Those voices, those elders—their ‘mata’ catching him, never letting go, sharing their stories, their lives with him—a poet—over a plate of rice and fish. What more was there? So influenced was Robles by the Poverty Scholarship of these elders, of the brown and black people whose daily lives and struggles moved in his blood that he dedicated his life to poetry and to helping take back the life and lives of his community. He wrote of his evolution to Poverty Scholar:

I travelled far back into the past

Searching for Ifugao Mountain

All the things I’ve learned

I threw out of my mind

All the books I’ve read

Were not worth one roll

Of toilet paper

And on the value of the knowledge of people in the barrios, and in the ghettos where he spent so much of his life observing the poetry, the sadness the tragedy and the triumph of life—observing those people whose experiences were not given credence or where vastly devalued:

Who is to say

The weeds are not

The roots?

Who is to say

The roots are not

The weeds?

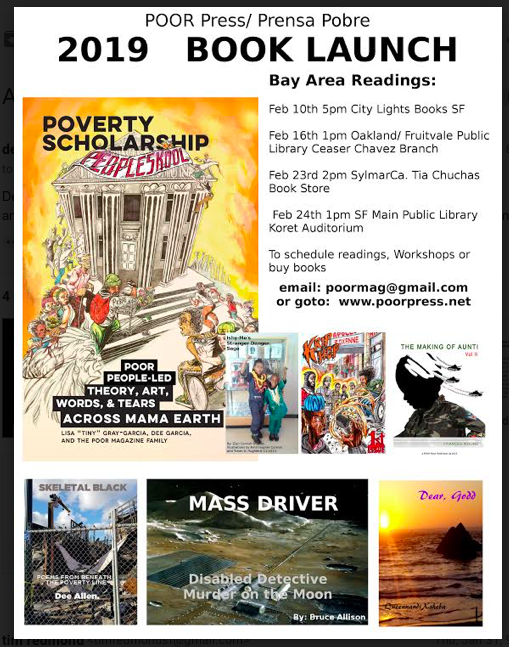

The work of Al Robles and other poverty scholars of POOR Magazine (Al Robles was a board member of POOR until his passing in 2009) are featured in POOR Press’ newest book, a beautiful collection of essays and poems and manifestos called “Poverty Scholarship: Poor People Led Theory, Art, Words & Tears across mama Earth.” This book is an extremely important text for schools, political groups, healers, community workers—all who are working to take back lives and create a better world—to embrace. It is a declaration, a new plan:

It’s called sharing the wealth

The accreditation and linguistic domination

Flipping the hierarchy

Of who is an expert

Who is a scholar

This book delves into practical ways in which Poor-People led education can inform the ways in which media is created, how service is provided, the liberation of landless and Poor People from poverty pimps and the multilayered world of social work that is a vortex that fees off people whose lands have been stolen, languages erased and whose presence is maligned, ostracized and criminalized.

The art and poverty scholarship that sings out from the pages of this people’s text brings about the emergence of hope and healing. One of Al Robles’ favorite songs was the jazz standard, “Tenderly.”

This book speaks with the fire of our indigenous blood and history, and tenderly shows us that there is another way — tenderly in a society that gives grudgingly. This book is a declaration of emergency and a guide book to regaining our bodies, spirits, hearts and minds. It is desperately needed at this time when, more than ever, we need to, as Poverty Scholar Al Robles said, “Take back our lives.”