It’s hard to believe, after I’ve spent more than three decades talking about the advantages of public power in San Francisco, that City Hall – including the Mayor’s Office – is finally coming around.

In a stunning report issued this week, the city’s Public Utilities Commission concludes that buying out the private utility’s local infrastructure and creating a full municipal utility makes financial and environmental sense.

It’s almost as if the SFPUC, which resisted public power under every mayor since the dam was built at Hetch Hetchy reservoir, went back and read this issue of the Bay Guardian (and about 100 others over the years) and realized: Hey, this actually makes sense.

The reality is that PG&E is falling apart, and made a huge political mistake when it picked a fight with the city over connection issues. The reality is that the private utility will never meet clean-energy goals, and the city can. The reality is that – when you look at the hard numbers – San Francisco can buy out the local infrastructure (thanks to the brilliance of Prop. A, more on that in a moment), create 100 renewable power, and still cut rates and probably wind up with excess revenue in the process.

And, of course, for the first time enforce the Raker Act, which requires the city to have public power.

The study, which is just preliminary, has been so far ignored by the Chron, although the Public Press covered it. It concludes:

- The city has been paying far too much money to PG&E for the transmission of Hetch Hetchy power, which San Francisco owns, to local agencies and customers.

- The city could buy PG&E’s local infrastructure – the power lines that are needed to deliver electricity on a retail basis – and still cut rates and provide more green power.

- The Board of Supervisors already has the right to vote for revenue bonds, backed by the money the city would make from its power utility, and it’s likely those bonds would come at a very reasonable interest rate.

- All of PG&E’s union workforce in San Francisco could move over to the city with no loss of wages or benefits.

In other words, creating a municipal power utility makes perfect sense:

The City can completely remove its reliance on PG&E for local electricity services through purchasing PG&E’s electric delivery assets and maintenance inventories in and near San Francisco, and operating them as a public, not for profit service. The City will pay PG&E a fair price for the assets that reflects asset condition. In this option, the City will also offer jobs to PG&E’s union and other employees who currently operate the grid. The City will expand the Hetch Hetchy Power publicly‐owned utility service to all of San Francisco, to provide clean, safe, reliable, affordable and sustainable service to all customers. The City will be responsible for upgrading and modernizing PG&E’s electric facilities in San Francisco that are aging or unable to support new supply and distribution grid technologies, and will be able to better control the pace and priority of those improvements.

The CleanPowerSF customer base, workforce, and supply commitments will be integrated into the Hetch Hetchy Power public utility, with service quality and affordability held accountable by San Franciscans through their local elected officials. Power independence for San Francisco will eliminate the need to fight for fair treatment from PG&E. City projects will no longer be affected by PG&E’s requirements and delays. The City will also be well positioned to meet its climate goals – through both supply‐and grid‐dependent actions – and efforts towards other critical priorities will be supported and advanced through comprehensive, local oversight of all electric services.

One of the factors that PG&E has always used to oppose a municipal takeover is the “billions” in potential costs to buy the system. The PUC recognizes that “billions” could be the price range.

That seems a little high to me, since PG&E’s entire market cap today – that is, the price of the entire company – is $18 billion, and San Francisco is only a small part of the company’s huge system, which serves 16 million customers. Fewer than 1 million of those are in San Francisco.

But whatever: In the many, many years that I have studied this, I have gone over all the figures in great detail, and the most important thing I have learned is that the price of buying the system isn’t that important.

It could be $1 billion, or $2 billion. Even at the high end, the interest on the bonds that would finance the buyout would be far, far less than the revenue the city would get from retail power distribution.

Tax-free Muni bonds that are highly rated (as SF’s would be) are paying about five percent interest these days. So we’re talking $50 million a year to pay the nut on a billion-dollar bond.

Double that? Pay $2 billion for the system? It’s $100 million a year in costs.

The SFPUC estimates that the revenue from sales of electricity in the city would be between $500 and $700 million a year.

The cost of the buyout isn’t an issue – at any reasonable price (and the system is going to be available for a reasonable price because PG&E is in bankruptcy) the city will make gobs of money on the deal.

As USF graduate student Matthew Chiodo reports in an upcoming paper, energy markets are complicated, but San Francisco already has a community-choice aggregation program in place, and can use that to purchase 100 percent renewable power on the market. It can also enter into agreements with solar and wind-power developers who can build medium-scale programs to serve the city.

And it can promote rooftop solar and make it easier to residents and businesses to put their excess power into the grid during the day and draw it out at night (without paying high fees).

The PUC report, of course, has some mangled history:

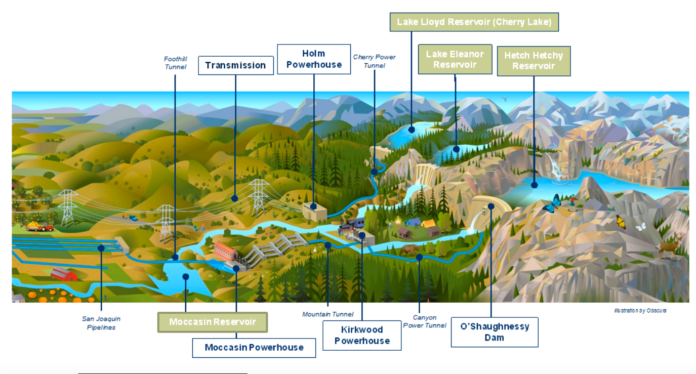

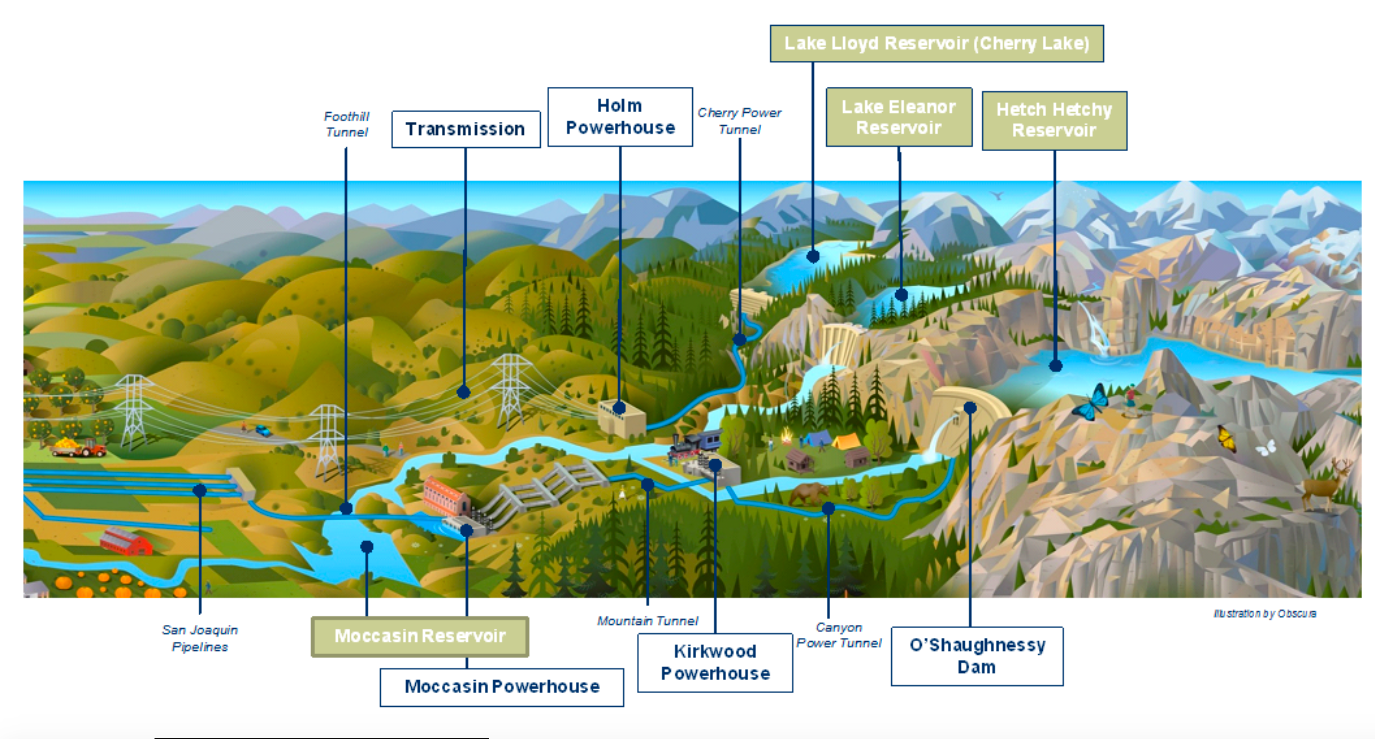

With the ongoing construction of the Hetch Hetchy Water and Power Project, and electric generation dating back as early as 1918, San Francisco set itself on a trajectory of measured independence from PG&E. Since the early part of the 20th century, the City has owned, operated and maintained generation and transmission facilities, and some distribution facilities. For decades, San Francisco purchased distribution services from PG&E pursuant to a series of bilateral agreements that allowed the City to deliver power to its numerous individual customers scattered throughout the City. These agreements with PG&E to purchase distribution services mitigated the need for the City to invest in its own comprehensive distribution facilities.

“Mitigated the need?” Actually, no: In a century-long scandal of stunning proportions, the city by law was always supposed to buy its own distribution system, but PG&E spent a fortune opposing the bond acts that would be needed to build that system and at least 10 times, defeated public-power efforts.

But whatever, those days are over. In a brilliant political stroke, Sup. Aaron Peskin figured out a way to authorize the board to issue revenue bonds for green power projects, and got Prop. A on the ballot with the unanimous support of his colleagues. It passed overwhelmingly, and now PG&E can’t block acquisition as easily. Revenue bonds don’t require a ballot measure that would be subject to a multimillion-dollar PG&E attack.

And the SFPUC is, finally, pointing out that it has the experience and staff to run a public utility. The argument that the city can’t run its own power system (another PG&E claim over the years) is falling apart as the PUC successfully takes on more and more energy projects.

So everything is in place for SF to create a municipal utility that can provide clean energy, local control, lower rates – and potentially a huge source of revenue for the city.