Sholem Asch was a brilliant storyteller. So brilliant was his 1906 play God of Vengeance that it drew standing room only crowds at theaters in Europe from St. Petersburg to Berlin. So genuine that it was a major hit in the Yiddish theater in New York’s Lower East Side. So controversial that when the play moved uptown to Broadway and was performed in English for an American audience in 1923, it caused an uproar leading to closure of the show and arrest of the actors on charges of obscenity.

So meaningful to Yiddishkeit, that it was performed by Jews in hiding in the Warsaw Ghetto. So poignant with themes that resonate today—religious hypocrisy, family condemnation of lesbian love, domestic violence—that Paula Vogel’s play about the play, Indecent, was received with wide acclaim and two Tony awards in 2017.

This week, the drama broke another barrier. Under the direction of Bruce Bierman, the Berkeley-based Yiddish Theater Ensemble performed God of Vengeance in a streaming video adaptation. The move from the originally scheduled live theater production was necessitated by COVID pandemic restrictions. The actors rehearsed and performed in their own separate spaces; the creative videography and innovative set design by Jeremy Knight brought them together.

The story, which has been transplanted from 1906 Poland to Depression-era New York City (the digital set design by Jeremy Knight was inspired by photos from the Tenement Museum), revolves around an observant Jewish couple planning an arranged marriage for their daughter Rivka who they claim is “as pure as if she was raised in a synagogue.” They have even paid for a hand-written Torah scroll to show how pious they are, and how much they can offer as a dowry. However, their fortune has been made on the backs of women they are exploiting as sex workers, who live and ply their trade in the basement below. Family and future begin to unravel when Rivka, who has been forbidden to ever go downstairs, befriends and then falls in love with one of the women, Mankeh.

Bierman also directed the video adaptation. He overcame my screen-weary skepticism about how this very human play could work on video, creating a sense of immediacy that lasted throughout the 90-minute drama. The opening scene of Torah scribe Julie Seltzer’s careful hand-penning of the Torah scroll, is mesmerizing, drawing the viewer into the realm of the sacredness of the word. The video interpolation is so flawless that it’s hard to believe the cast was never in the same room together. Even during the most intimate moment—the rain scene where Rivka and Mankeh celebrate their love with a kiss (the first lesbian kiss on Broadway, and one of the reasons the play was censored)—you can almost feel the rain, and their passion.

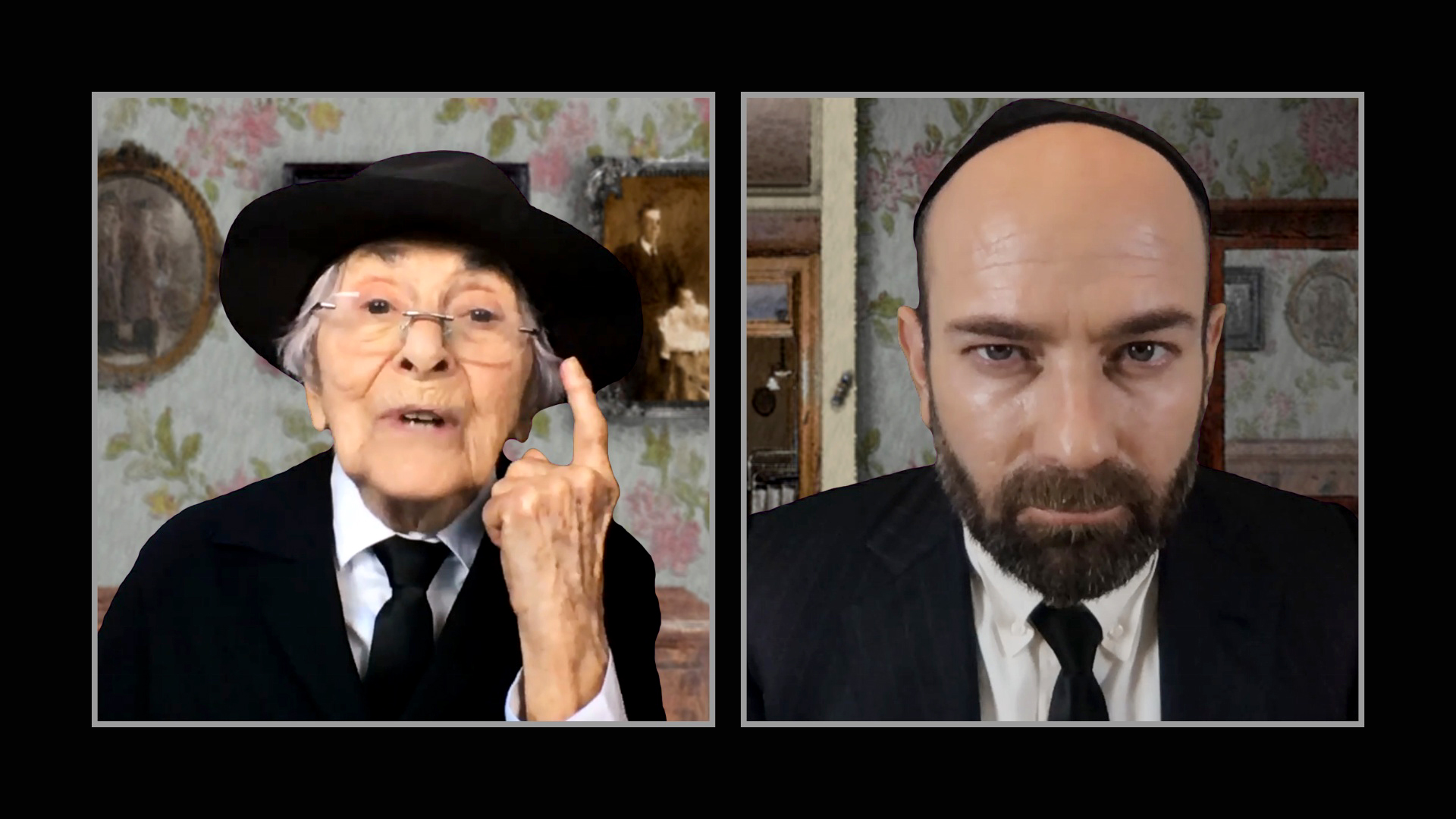

Despite the pandemic obstacles, the 17 actors in the diverse cast give outstanding performances, literally from around the country. Elena Faverio (Rivka) believably turns from a sulky adolescent into a bold young woman, 90-year old veteran actor Naomi Newman is a cleverly engaging matchmaker Reb Eli, and Jill Eickmann (playing Rivka’s mother Soreh) conveys every subtle emotional shift with her facial expressions. Her transformation, reflected in a mirror, as she puts on make-up, lets down her hair, and plots to bring her daughter back home, is one of the most powerful scenes.

This production of the play was translated into English by Caraid O’Brien, who peppered the script with enough Yiddish to recreate a mid-Twentieth Century Jewish home and neighborhood. As producer Laura Sheppard notes, this is a “family drama story that has extraordinary tenderness, elements of Greek drama—and a bisl (little) Yiddish.”

Though this run was only from March 20-23, the company is hoping to present it again later this year. The production is part of the 40th Anniversary of the Yiddish Book Center and sponsored by KlezCalifornia.