In vītatio (through May 25 at Altman Siegel, SF), K.R.M. Mooney curates a group show that conjures both invitation and avoidance—the linguistic attributes of the title—featuring 10 artists whose work spans space and time. Yet they share Mooney’s thoughtful relationship to materials and fabrication without sacrifice to nuanced conceptual concerns, coalescing to create a third space in the wake of racial/colonial violence and outside the trap of gendered binaries.

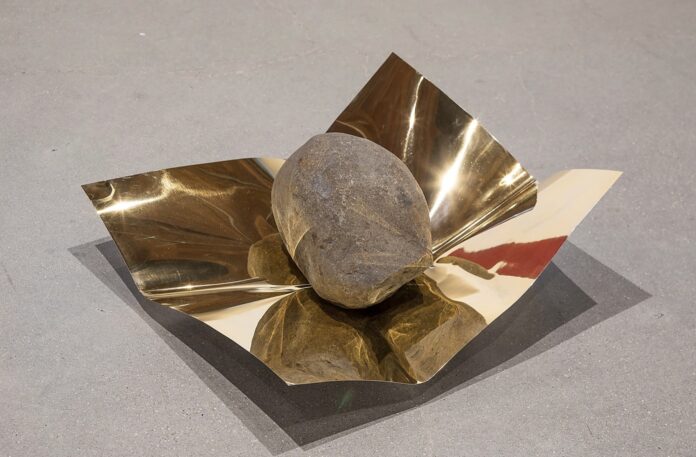

On the floor near the gallery entry is a large round rock positioned on top of a gold sheet of metal which has been warped upward, lightly enfolding the edges of the stone almost like a crumpled piece of paper. Seeing disparate materials fit together just-so is visually satisfying; the poetic combination feels like an embrace, and makes one envision the force needed to bend metal in such a way. Are we to imagine the rock falling from the sky with enormous impact like a meteor splashing into the ocean? Or was the metal carefully gathered around it like kraft paper surrounding a bouquet?

The materials list indicates that the stone is not just any rock, but a ballast stone—like the type historically used in ships to stabilize their weight. The work by Zarouhie Abdalian, entitled Hull, utilizes overlooked tools of labor and capital as a way to highlight the histories of the laboring bodies that are associated with these materials. During the transatlantic slave trade, ballast stones were used to counterbalance the weight of enslaved people being transported. In this reading, the material takes on an entirely different emotional weight—and becomes a haunting referent to a person whose humanity was violently discarded.

The exhibition sensitively and powerfully expands this idea of referring to loaded personal and collective histories through absence, or uncommon access points. I keep revisiting the idea of what is referred to obliquely for those in the know, what is left unsaid, and what is redacted from the audience’s view as a form of refusal, delicate gestures whose power only grow the longer you spend in the exhibition.

Every piece in the show operates on multiple planes simultaneously—Hudson River (III), 1976 by Peter Hujar might read as a beautiful closeup abstraction of water to one viewer, and reflect psychically in space and time towards cruising on Christopher Street Piers for another. Mooney seems to be playing with these varying levels of opacity in his curatorial approach—each included artist has their own strategies to circumnavigate the double-binds that emerge as they traverse this moment and also tend to the enduring echoes of history.

Oakland-based artist Bri Williams’ sculpture Untitled (vanity), transmogrifies a found medicine cabinet with a cracked mirror into a spectral container for a flowing chiffon skirt that hugs the cabinet’s void, the black translucent edge of the fabric hovering in midair like a ghostly flag. It’s almost as if Williams has suspended a life-force escaping from this domestic vessel, evidencing the psychological heaviness contained within the objects that we interact with every day.

Three gestural portraits drawn on brown paper in graphite by Reggie Burrow Hodges initially seem like life-drawn studies of models for a later painting, but the titles’ prefix (Invented Portrait Study) imply that these drawings aren’t actually based on physically existing individuals—even though the specificity of their suffixes (Harper, Squealev, Pierce) and the distinctive qualities of each subject suggest otherwise. Hodges foregrounds the slipperiness of sight and memory, indicating that what we can’t see is just as important as what we can, positioning these studies to become a mirror of expectations, assumptions, and structures as much as they are figural representations of people.

Fred Wilson’s Untitled (Bust), performs a détournement to a Grecian-looking sculpture that has the neck cracked off, with a small figurine of Egyptian pharaoh emerging from the alabaster interior like a matryoshka doll. The relationship of these two symbols as Wilson has situated them forces the bust to become not just a noun but a verb, reframing history and recalibrating what is valued and emphasized (the Grecian bust becomes a pedestal/vessel to house something much more precious). Thinking of a third definition of the word, the statuette inside becomes contraband, perhaps in reference to the many stolen Egyptian artifacts that remain in museums all over the world to this day. Wilson’s seemingly simple gesture creates an infinite exchange about history and the construction of race as molded by institutions, and its interaction with capital with a deft sense of humor—checkmate in two moves.

Cameron Rowland’s Background frames the two blank copies of FBI Form FD-258 (used to do background checks) in a diptych together showing recto and verso. Rowland’s conceptual practice uses found objects to map out the lineage of how the carceral system in the united states is a continuation of chattel slavery, and often creates unconventional rental/payment structures for artworks as a way to highlight the lasting impact of humans being classified as property and to advocate for reparations. In this case, the form FD-258 becomes a container for the bureaucratic banality of how racialized state violence manifests and is perpetuated.

Dahn Vo’s contribution to the exhibition is a decontextualized photogauvre of Barbara Pierce’s (“Mrs. George H.W. Bush”) 1945 New York Times wedding announcement to the former Vietnam War-supporting politician, which the artist has exhibited previously near his own grandmother’s obituary. Here, the news clipping stands alone, an absent referent prodding at the ironies, contradictions, and paradoxes of colonialism. 6.12.1945 suggests how politicians’ detrimental actions are sanitized and buried under the sand by the smiling white wives standing by their sides.

Fortunately this exhibition also gives the Bay a porthole into the practices of several of the artists whose work is currently being shown at the 2024 Whitney Biennial “Even Better than the Real Thing”: Kiyan Williams, Harmony Hammond, and curator Mooney.

Kiyan Williams’ earth and silver study, 1, is a stretched canvas covered in textured dark soil that is dry and cracked, appearing almost scorched, which is overlaid with silver at the top, transitioning between the two shades like a color field painting. The soil is actually coated with silver nitrate—a chemical compound that was historically used to cauterize wounds—invoking possibilities of repair and recovery and connected the start gallery space with something more earthly, real, and bodily. The cracks are precarious and beautiful, suspended in a state of transition and defying gravity in their verticality, becoming and dematerializing, between heaven and earth.

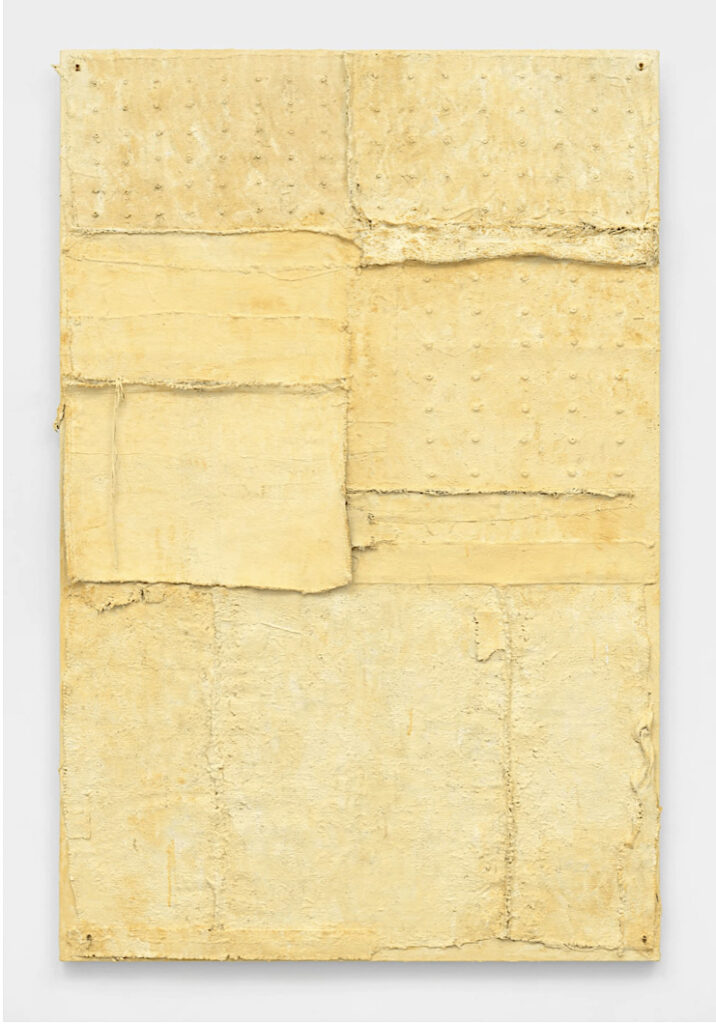

Harmony Hammond’s Chenille #10 is a large canvas layered in various scraps of frayed burlap and other fabrics, all coated with a thick layer of paint that’s the color of buttermilk, punctured from behind with grommets. The thickness of the paint unifying the collaged layers of canvas-cum-rags point towards queer domestic experiences, carving a path between functional and decorative that metamorphizes materials into something else entirely.

There is a poetic efficiency to the works on view in vītatio, and this wide-ranging exhibition poses important questions about the potentialities and limitations of subtle subversion as situated within art institutions. vītatio is a must-see show on view at Altman Seigel through May 25, 2024.

vītatio runs through May 25 at Alman Siegel, SF. More info here.