>>We need you! Become a 48hills member today so we can continue our incredible local news + culture coverage. Just $20 a month helps sustain us. Join us here.

If the de Young museum’s major retrospective of photographer Irving Penn (through July 21) was a PhD dissertation, the thesis might be this simple: Never underestimate a kid from Jersey.

Surely, no one crossing paths with the quiet, sensitive boy whose parents were Russian Jews and whose contentious divorce amplified their son’s outsider identity would have regarded the young Penn and said, “I see a future great photographer of the 20th century.” Nor could they have predicted his 70-year career would include classic portraits of high-profile celebrities, artists and cultural luminaries such as Audrey Hepburn, Alfred Hitchcock, Picasso, Truman Capote, and Joan Didion. Still more portraits of tradespeople, laborers, hippies, and everyday folks—not to mention images of discarded cigarette butts, mud gloves, oriental poppies, stones, and even line drawings and paintings eventually filled out his creative portfolio.

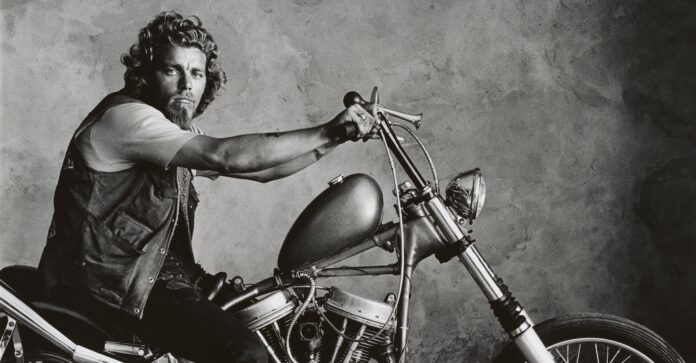

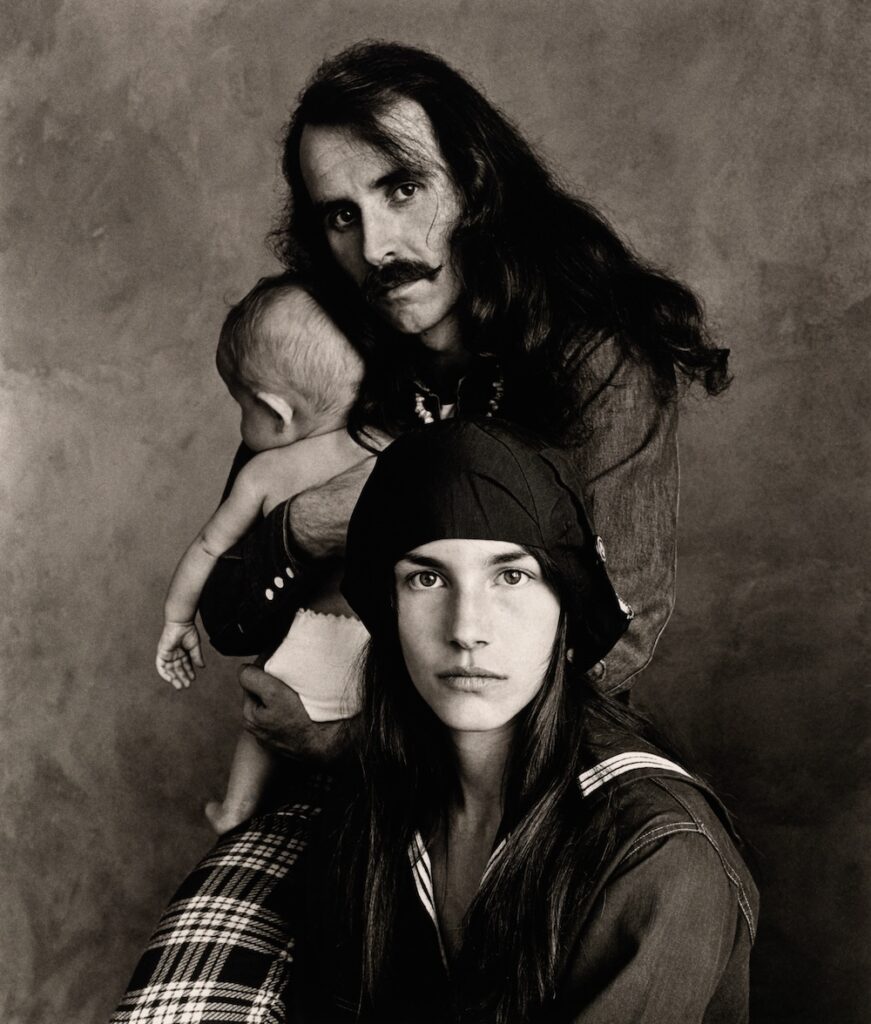

The kid from Plainfield, New Jersey—he attended high school in Brooklyn and studied design in Philadelphia—opened his lens for six decades. In the fashion world, he worked as a regular contributor to Vogue and in 1967 was commissioned by Look magazine to travel to San Francisco during the Summer of Love. In the Bay Area, he documented the Hells Angels, the Grateful Dead, Big Brother and the Holding Company, and members of the San Francisco Dancers’ Workshop posing nude in his tightly cropped, nearly abstract images.

The 175 photographs in the de Young exhibit, along with magazines and other materials, collectively characterize Penn as a quiet observer always outside his subjects and yet, an artist whose images comment with raw honesty and intimacy on a subject’s essence or social context.

>>>READ MORE: HOW IRVING PENN BROUGHT THE WORLD TO HIS STUDIO—AND VICE VERSA<<<

Emma Acker, curator of American art at Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco tells 48hills, “[Penn] was famously soft-spoken and unimposing. During photo sessions, he’d try to bring out the core of his subjects and slowly draw out what he perceived to be their essential qualities. He was a keen observer and fascinated by a whole range of subject matter.”

Penn often moved the people sitting for photos during the sessions, meticulously adjusting their bodies and the lighting to bring forth an individual’s subtle qualities and enhance their more obvious features and energy.

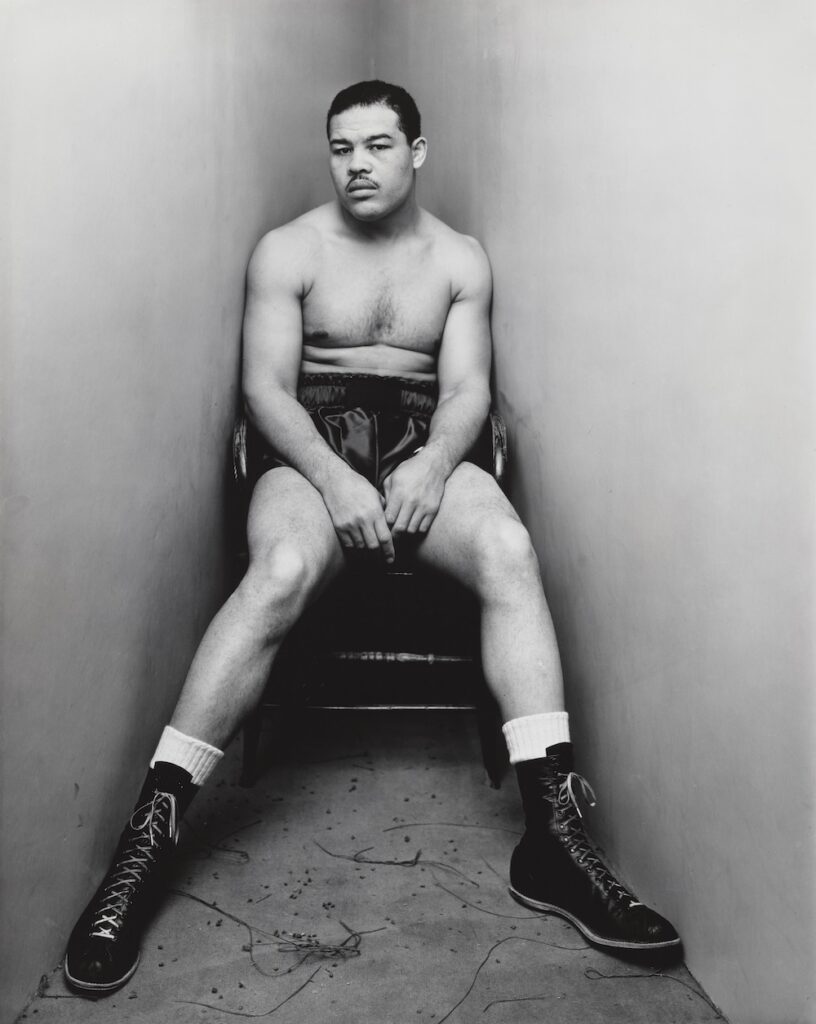

“In his portrait series, he created constraints his sitters reacted to,” says Acker. “The conditions he sets for his subjects are consistent, like the corner portraits, where sitters are in a confining space and other photos where there’s a pared down, neutral, backdrop setting. (A photo of Georgia O’Keeffe demonstrates both concepts brilliantly.) He treated fashion models, entertainers, laborers, and people across the world with consistent aesthetic settings. He took himself out of the pictures, and let the subjects shine against the neutral backdrops.”

Ultimately, Acker suggests, Penn viewed world cultures through an artistic lens and presented images that allow the viewer to recognize and respond—or not—to the things they shared with the images’ subjects. One example: photographs Penn made of Quechuan Indians in Cuzco in southeastern Peru that demonstrate the consistent and astute eye for fashion and steady respect for subjects that Penn brought from Hollywood to the Hells Angels and beyond.

Penn was also perpetually experimental. “The technical aspects of his work show this best,” says Acker. “You see his radical experimentation throughout the exhibit. For his series of nudes that he began in 1947, he worked in a private darkroom on nights and weekends while exploring a concept outside of the commercial confines of Vogue. For his first work in this series, Nude no. 1, he used a paper negative rather than transparent film, and with the mottled texture the paper imparts and the radical cropping he incorporated, the resulting image feels like a Paleolithic stone sculpture.”

The texture created with the technique renders unique, sculptural aspects of human skin. The fleshy models he gravitated to for his off-the-radar work—he was tired of skinny models and preferred “real women in real circumstances,” he once said—along with a modernist approach, allowed women’s bodies to be seen whole, sensuous. The work caused Penn to be renewed, inspired, and engaged. “It came at an important time. He felt picture magazines had reached a dead end,” says Acker.

The de Young exhibit was organized by The Metropolitan Museum of Art. In the Bay Area, the retrospective includes an expanded section on Penn’s San Francisco photos and images he made of dancers performing U.S. choreographer Anna Halprin’s The Bath. A marvelous catalogue offers essays that contextualize his work within the frames of both U.S. history and the world of photography.

Throughout the artistic progression put on display at the de Young, Penn’s unmistakable drive is obvious. “He was constantly challenging himself, looking at the work of older photographers and artists working in other mediums and wanting to do the same things himself,” says Acker. “The process for creating platinum-palladium prints was in some ways more akin to painting or printmaking than photography. And Penn would find beauty in cigarette butts and things that were decaying. He had a different idea of beauty than you’d expect from a commercial product photographer. He recognized the element of death and decay in beauty. You can see the full spectrum of human experience reflected in his work.”

Acker says local response to the Summer of Love photographs has been especially strong. To take the portraits of the Hells Angels and SF counterculture figures, Penn rented a studio and constructed a concrete wall. The blank, neutral backdrop enhanced the poetics of Penn’s lighting and the viewer’s focus shifts to how light falls across a body, a face, a motorcycle. In the minimal shadows created, there is marvelous mystery, danger, decay, and edgy reality.

“We’ve had a positive response to this section, given our location. It’s interesting that the photographs are wonderful documentation of a moment of transformation,” says Acker. “They capture the fashion and styles, but also the change that was happening. They’re sensitive representations of the subjects. The attitudes they project and their outfits were real symbols.”

Penn’s Summer of Love photographs telegraph the intimacy of families and in some ways, show tenderness and conventionality. At the same time, they never lose track of the non-conformist attitudes inherent in the subjects’ lifestyles and attitudes. While he traveled society’s upper echelons, Penn was still that young boy looking at the world, seeing both its glamor and its grit.

Acker says, “He’s honest. By deconstructing and showing the artifice of studio photography, his work was the antithesis of Photoshopped, Instagram-ready imagery.”

IRVING PENN runs through July 21. de Young Museum, SF. Tickets and more info here.