How vital cell phone networks are reaching rural areas that corporate telecommunications have written off

MEXICO CITY, MEXICO — A few years ago, the Oaxacan mountain town of Santa Maria Yaviche had 700 indigenous Zapotec residents and no chance of getting cell phone service for any of them. It is a common story in rural parts of the world: telecommunication companies lose more money than they make building far-flung phone networks, so they just don’t bother. No laws exist in Mexico to protect small communities from this kind of treatment, so Santa Maria Yaviche was left high and dry. Luckily, corporate tech was not the community’s only option.

Over the past year, an organization called Rhizomatica has been busy erecting 16 telecommunication networks in communities previously passed over by Carlos Slim’s América Movil empire and other phone companies in the state of Oaxaca, where 61 percent of the population lives below the poverty line.

Today, over 100 Santa Maria Yaviche families have their own phones. “Before, we thought that only people with money could have this type of technology, or educated people,” Oswaldo Martinez Flores, a 38-year-old Zapotec farmer from Santa Maria Yaviche told 48 Hills. “Today, it seems like technology is for everyone.”

Martinez remembers what life was like before the cell phones arrived.

Looking for work outside the small community was nearly impossible, and workers who suffered on the job accidents in far-flung agricultural fields were out of luck as far as receiving prompt medical attention was concerned. The town first got limited use satellite Internet service in 2008, but phone service was limited to a single telephone booth, and then a complicated radio wave system.

Corporate telecommunications companies charged 6-8 million pesos to install a network, far beyond the means of the Santa Maria Yaviche campesinos’ salaries. América Movil owner Carlos Slim may be the richest person in Mexico (and one of the richest in the world, with a estimated personal worth of 72.9 billion dollars), which means he’s out to make a buck. Santa Maria Yaviche just wasn’t green enough of an investment. “We resigned ourselves to not having those means of communication,” Martinez said.

Oswaldo Martinez Flores walks you through his town’s cell phone network, and talks about the results its brought to Santa Maria Yaviche (en español)

That is, until he and some of his neighbors met Peter Bloom in a community radio workshop.

“Generally, people find us because they think it is important,” said Bloom in a 48 Hills interview. At the time of meeting the residents of Santa Maria Yaviche, he had recently moved to Oaxaca from Nigeria, where Bloom had dubbed his efforts in mobile mesh networks and digital community defense Rhizomatica. (Rhizome refers to a philosophic model embracing heterogeneity and non-hierarchal order.) Love brought him to Mexico, but once reunited with his partner there, he turned his interests towards the country’s underserved rural populations.

Bloom petitioned the Mexican government, and received the first license ever granted to a civilian organization to access mobile radio frequencies. Soon after, he began making presentations in academic, regulatory and hacker conventions, Oaxacan indigenous communities, and cultural spaces all around the country. “People were and are in need of inexpensive communications,” Bloom said. “That allowed us to come in contact with lots of communities.”

Santa Maria Yaviche paid 150,000 pesos for one of Bloom’s networks, far below corporate price points. Once it was completed, the network remained in the possession of the community, though Rhizomatica does provide ongoing support. Today, the project employs eight people in Mexico and has installed 16 networks throughout Oaxaca. In 2015, Bloom was named one of MIT’s Innovators Under 35 for his efforts.

For Bloom, the project brings attention to the fact that without vigilance, advanced technology does not always serve the general population. Around the world, he said, private companies are lobbying industry regulation down to nothing, a process that is called regulatory capture and often leads to privatization. Bloom sees projects like Rhizomatica that put control over telecommunications back in the hands of the general population as a possible fix to this situation. But greater shifts are needed. “We need to first question why the only ones considered “fit” to access spectrum are companies and then figure out how to change this dynamic,” he said.

Currently, Rhizomatica is taking a step back from new installations in order to focus on keeping in touch with on-site network administrators and otherwise supporting the networks that already exist. Weather can damage networks, battling political factions can stall operations, electrical grids can go down, handicapping phone service for the community in the area. Bloom says the company is in the process of hiring more staff and building internal systems, and that it hopes to return to new construction shortly.

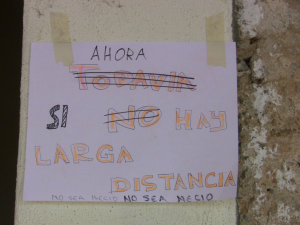

In Santa Maria Yaviche, residents pay 30 pesos a month for unlimited local calls and texts. Calls are funneled through a general number, which greets you with a message in the Zapotec language. Many families already owned a smart phone when the network was first implemented – they had been using them to store music and take photos. Martinez sees big changes for his town having resulted from its new wired state.

“We use [our phones] to promote local products, to look for work,” he said. “Basically they mean energy saved – before we’d have to travel to another place to do these things, but now we can do them from home.”

“There’s more communication within the community,” he continued. “Women have access to communication, young people. Government administration is more efficient. Our children begin from the time that they are small, using these means of communication. It makes you realize that everyone has the same rights and that we can do things for ourselves.”