San Francisco is moving closer to having its own public bank.

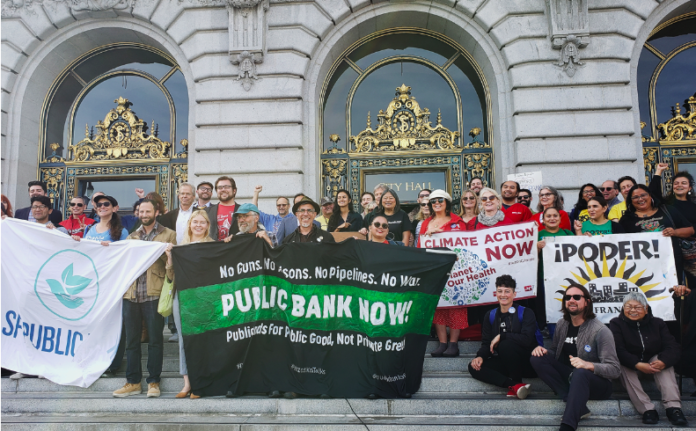

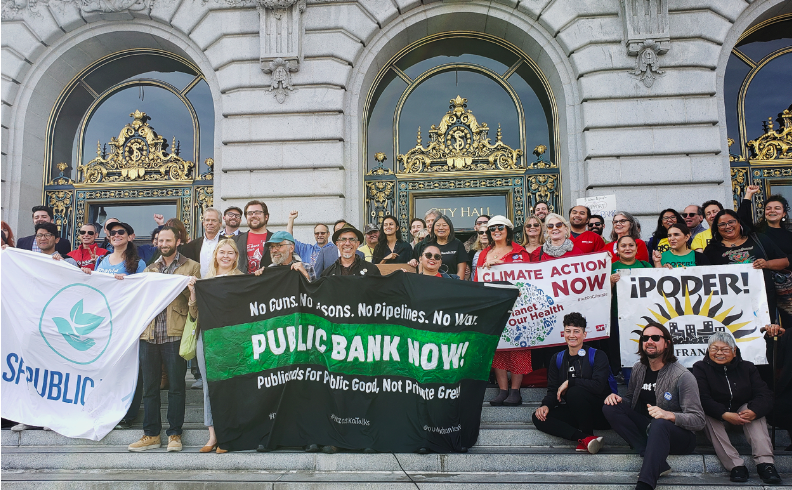

Today, Supervisor Sandra Lee Fewer, alongside the San Francisco Public Bank Coalition, gathered on the steps of City Hall to announce she is introducing legislation to establish the Public Bank of San Francisco.

If this legislation moves forward, San Francisco would be the second public agency in the nation to form a public bank after North Dakota, which created a public bank in 1919.

The San Francisco Public Bank Coalition has called on San Francisco to divest approximately $11 billion dollars of taxpayer money from private commercial banks and invest it in a state-chartered, municipally owned public bank.Advocates assert that moving San Francisco’s money from Wall Street banks into its own bank would allow for greater control of how taxpayer money is invested and would better reflect SF values and priorities, including investing in affordable housing, small businesses, and renewable energy.

“San Francisco taxpayer money is currently held in private and commercial banks that often engage in socially and environmentally destructive practices fundamentally against the values of San Francisco,” said Fewer. “A public bank in San Francisco would allow the city to have more local control, transparency, self-determination, and deepen critical community investments in affordable housing, small business development, loans to low-income households, public infrastructure, renewable energy, and addressing the student debt crisis.”

Fewer’s legislation, which is co-sponsored by Supervisors Shamann Walton, Vallie Brown, Gordon Mar, Aaron Peskin, and Matt Haney, sets a timeline for the establishment of the public bank. A nine-member task force of experts appointed by the Board of Supervisors would meet monthly and oversee the development of a business plan that would have two phases:

Phase one of the business plan would refer to the creation a non-depository institution, an Economic Development Financial Institution (EDFI), which would consolidate and deepen the city’s lending for community benefit (i.e. affordable housing, local infrastructure, small businesses) and does not require federal insurance or regulatory approvals. The task force would be required to submit the business plan for phase one by June 2020.

By December 2020, the task force would have to submit a plan for phase two, which would refer to the EDFI applying for a public banking charter with the State of California, turning it into a completely developed public bank that could take deposits and take on the city’s banking services.

If all goes as planned, San Francisco would be in line for a public banking license by the end of 2020.

“What we have today is a legacy of two different movements, namely Occupy Wall Street and the No Dakota Access Pipeline movement,” said Jackie Fielder of the San Francisco Public Bank Coalition, which includes organizations such as SF Defund DAPL, PODER, the Council of Community Housing Organizations, and DSA SF. “This is a result of people power and a grassroots movement led by organizers and advocates that took years of work and dedication,” Fielder said.

Supporters of a public bank in SF agree that this has been a long time coming. In the wake of the 2008 financial collapse and the subsequent Occupy movement, former Supervisor John Avalos explored the idea of a publicly owned bank years later in 2011 and called for a city report to review its feasibility. Momentum stalled until the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline in 2016, which put a spotlight on the investment of public dollars towards pipelines and fossil fuels that disproportionately impacted indigenous lands.

In response, San Francisco began to explore how to separate taxpayer money from investing in fossil fuels. In 2017, the SF Defund DAPL Coalition was formed, and what started out as a call for SF to divest its money from Wall Street banks and financial institutions that were bankrolling the Dakota Access Pipeline evolved into a call for municipal control of public funds. Former Supervisor Malia Cohen then established a municipal bank task force in 2018 to review its feasibility, reviving Avalos’s idea.

While little came to fruition after the 2011 report, Avalos has been an active advocate in the current effort to create a public bank and supports bold progressive ideas to create equity for communities. “We’re living in a world where there’s widening inequality and huge disparities in wealth,” said Avalos. “Incrementalism is not working. This is how we got here today. I am thrilled to see this happening,” he said.

The establishment of a Public Bank of San Francisco got a major boost with the passage in September of AB 857, which allows California municipalities to charter their own banks. Assemblymember David Chiu, who co-authored the bill with Assemblymember Miguel Santiago, described AB 857 as one of the hardest bills he’s ever had to move in the legislature, as it went through six committee votes and three floor votes.

Despite Wall Street lobbyists insisting that the push for public banks is misguided, Chiu said he believes that public bank organizers and advocates have made their case. Many members of the SF Public Bank Coalition aided Chiu and the California Public Banking Alliance at the state level to get AB 857 passed.

“The vision of public banks is that our public money should be invested in industries and communities that have a public purpose… Our public money should be invested in our local communities, in local infrastructure, in local housing. Our public money should not be used to line the pockets of the [wealthiest] Wall Street Banks,” said Chiu.

“San Francisco should lead the pack in this effort and today’s legislation moves us one step closer to realizing the creation of a public bank,” Fewer said.