If you’re looking for a delectable entry point into ballet today, San Francisco Ballet has created a program expressly for you. Classical (Re)vision, playing through February 22, is billed as a “tasting flight of contemporary ballet.” But the evening-length selection of shorts, bookended by two longer pieces (Bespoke by Stanton Welch and Sandpaper Ballet by Mark Morris), is more satisfying than that tagline suggests. On opening night, there was hardly a ho-hum merlot or stinker rose in the bunch.

The shorts, chosen by artistic director Helgi Tómasson, are different in each performance. That’s a very clever way to introduce variety, and to deal with an emergency: Hummingbird, a longer piece by choreographer Liam Scarlett set to music by Philip Glass, was pulled from the program a couple weeks ago, after the New York Times reported that Scarlett was accused of sexually assaulting Royal Ballet students.

That the company could quickly replace Hummingbird with these sparkling works from its repertoire is a tribute to its resilience. Val Caniparoli’s kinetic “Foreshadow,” premiered just last month at the Ballet gala, flashed with existential angst with erotic expressionism: It’s Tolstoy’s love triangle of Anna Karenina (Jennifer Stahl), Count Vronsky (Tiit Helimets), and Kitty (Elizabeth Powell) bumped into nervy Dostoyevsky territory and staged as a silent movie thriller.

I haven’t always dug British choreographer Christopher Wheeldon’s work—his stakes never seem high enough to me—and he chose one of composer Arvo Pärt’s more stolid pieces for the pas de deux from his 2005 “After the Rain.” But Yuan Yuan Tan and Luke Ingraham slowed time and performed a tender, meandering meditation saturated in a feeling of belatedness, which brought to mind Edward Albee’s more abstract plays. (A crucial assist was Mark Stanley’s lighting design, which transformed the stage into a glowing coral beach.)

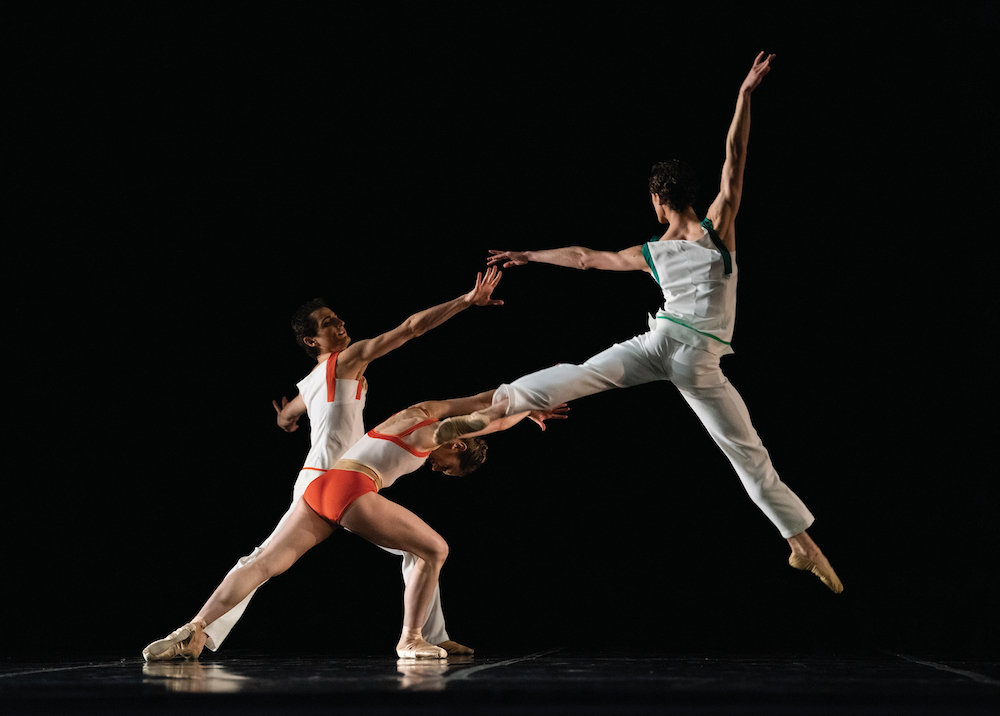

“Soirées Musicales” by Tomasson himself, from 1996, proved to be the most head-scratching piece for me. With heavily brocaded velvet costumes by Ann Beck and plenty of old-school flourishes, it was certainly rousing (Benjamin Britten’s score is a march-like romp). I searched for any glint of irony, but eventually just surrendered to the overwhelming classical force of Angelo Greco’s unbounded leaps and partner Misa Kuranaga’s dramatic spins. This wasn’t revision as in update, but revision as in seeing afresh.

Bespoke kicked off the evening with a spirited if opaque look at what it’s like to live a dancer’s life, full of love for the art. Clothed in Holly Hynes’ anything-but-bespoke costumes (they looked like rehearsal outfits with streaks of pastel color), the dancers glided through Welch’s eye-pleasing formations with just enough momentum to wonder what was coming next. (There probably should be an injunction on setting new pieces to Bach, though, in this case two early-1700s violin concertos—the beauty comes too easily, and the aesthetic connections between Bach’s musical math and the language of choreography have been exploited to death. But I’m the last person to complain about hearing anything by Bach performed live.)

Bespoke didn’t quite earn its dramatic and affecting ending (death slowly descends on the corps) and its central pas de deux was strangely inert, but the whirlwind combinations of threes and fives throughout kept things lively, if airily abstract. There was one disruptive passage that hinted at a direction Welch could have taken. With all of the dancers gathered onstage, a robotic freestyle broke out during a particularly techno-like line in the Bach. Then there was a very brief flash of movements taken from Balinese and Maori dance (Welch is Australian) which blew the piece wide open and hinted at a deeper, historical meaning. Maybe it was intended to symbolize dancers in their cheeky and searching youths. I wanted more of that.

The night ended with a marvelous piece by Mark Morris that I’ve been wanting to see for a while, Sandpaper Ballet. Morris is seen as our foremost purveyor of camp sensibility. But with him that means infusing everything with giddy shock at the underlying ridiculousness of contemporary life—whereas our hot-take culture has reduced “camp” to merely signal arch snark. Building on Balanchine’s barrier-melting generosity of spirit, Morris’ works often feel like team exercises that extend to the audience. You’re here, we’re here, let’s have some fun.

Sandpaper immediately plunges us into funhouse Americana, with 20th-century popular composer Leroy Anderson’s lush score summoning 1950s television soundtracks and auto showrooms, full of concrete associations like typewriters and ringing phones—one clip-clopping woodblock rhythm impelled a dancer to high-step hilariously offstage. (The ballet orchestra, under the direction of Martin West, astonished.) Dancers swayed in lines like paper dolls, swaggered in posses with swinging hips, or roiled like an impossibly busy crosswalk. Aaron Copeland’s rootin’-tootin’ Western mythos and Dr. Seuss’s folksy surreality were both summoned. Isaac Miszrahi’s “green screen meets big Magritte sky” costumes united both, and added a dash of opera-gloved glamour, a la Holly Golightly.

Every detail was toyed with—at one point, members of the corps feigned jealousy and attraction towards the featured soloists. Even the name, Sandpaper Ballet, is a bit of a laugh: The Anderson composition by that name wasn’t even included, so you’ll just have to Google it yourself when you get home.

CLASSICAL (RE)VISION

Through February 22

SF Ballet at War Memorial Opera House, SF

Tickets and more info here.