Black people in California are almost ten times as likely as white people to get minor infraction tickets that can add up to hundreds of dollars and lead to arrest, a new study shows.

The report, by the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights, looked at data from the 250,000 citations issued by police in the state of non-traffic crimes that are punishable by fines.

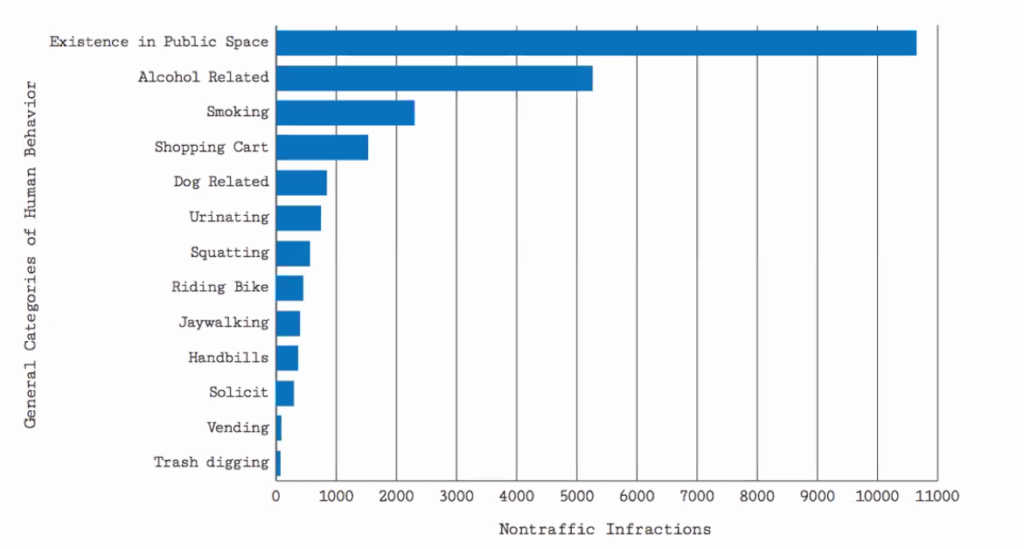

The largest number of those citations – 37 percent – were for the “crime” of existing in public space. Many of the people who got those citations were experiencing homelessness, and can’t possible afford to pay fines and fees that can quickly add up to almost $500.

Latinx residents are 5.8 times as likely as white people to get non-traffic citations, the report shows.

“These are tickets for minor behavior that have major impacts,” Elisa Della-Piana, one of the authors of the study, said this morning.

Most of the citations, she said, are for sitting, standing, or sleeping in public spaces or for curfew violations. “Never in any of these cases is there harm to a person or property,” she said.

The Lawyer’s Committee used the California Public Records Act to compile data on these non-traffic infractions – and one of the things they learned is that most jurisdictions in the state don’t keep track of the citations by race.

But the citations are a big deal: Between 2006 and 2019, there’s been a 97 percent increase in laws criminalizing camping in public, Tifanei Ressl-Moyer, another study author, said.

The citations are used to “criminalize everyday behavior” that white people and people with housing never get cited for, Tori Larson, who also worked on the report, said.

The citations are racist – and target people who often have no ability to pay. Almost half of the tickets never get paid.

“The data studied for this report shows a pattern of enforcement of petty laws against California’s Black, Latinx and unhoused residents, enforcement that would not be politically tenable if it targeted wealthy white Californians,” the study notes.

“In interviews of people ticketed, no one was fined less than $100, and most people were charged between $250 and $500, which is consistent with California’s fee schedule. A survey for this report of 10 counties found that half of the counties still issue warrants on non-traffic infractions for people who cannot or do not pay or appeal. California has over $10 billion dollars in uncollectable infraction debts, and in the meantime, thousands of people are at risk of arrest for the most minor of violations.”

In other words: A homeless person, particularly if that person is Black or Latinx, gets a ticket for something like loitering (which I didn’t think was even a crime in this state anymore) or sitting on the sidewalk or putting up a tent (or walking a dog that doesn’t have a license).

The person can’t possibly pay $100, and in some cases many not even have the money to take the bus to court to contest the cite.

So the fine goes unpaid, and a judge issues an arrest warrant (which doesn’t happen in SF but does in many counties) and suddenly a person whose only “crime” is being Black and homeless faces arrest and jail time.

“Most common are citations for everyday human behaviors such as sitting, sleeping, and standing, and the cause for citation amounts to existence in public space; included in this category are citations for loitering, curfew violations, and sleeping or camping,” the report states.

“This is not an issue for people who can afford to pay hundreds of dollars in fines and fees. For low-income Californians who cannot afford to pay the fines, this means that what started as an act of ordinary human behavior—sitting, walking across the street, standing and talking to friends—can escalate quickly to arrest and jail.”

And this is costing a lot of money:

“Between 2013 and 2017, police dispatches regarding “homeless concerns” [in San Francisco[] increased by 72%, despite no corresponding increase in the unhoused population. In 2015, San Francisco spent around $20.6 million dollars on enforcing 30 types of non-traffic violations; $18.5 million of that was paid to police. In 2015, the Office of the City Administrative Officer for Los Angeles reported that it expected the cost of the city’s homelessness services across all agencies to be an estimated $100 million per year The same report indicated that anywhere from 53% to 87% of the City’s expense comes from the Los Angeles Police Department’s interactions with unhoused people.”

The report concludes that the only solution is to get rid of these infractions:

“California does not need non-traffic infraction enforcement. Though many Californians were attached to the policing and punishment of marijuana possession, it was abolished given the racism embedded in enforcement and the relative innocuousness of having marijuana. Many of the non-traffic infractions that remain on the books, like loitering and sit/lie laws, have an even more racist history. The current enforcement of these infractions has similarly deep racial disparities, as demonstrated in this report. And the behaviors our current system punishes are even more innocuous.”

The authors conclude:

“It may be tempting to advocate solely for back-end solutions to the harms outlined in this report, such as reducing fines and fees if people prove they cannot pay. The authors of this report used to advocate for ability to pay as a solution to fines and fees in California, and after years of experience in design and implementation, have concluded that: (1) they don’t work–in two counties, approximately 50% of low-income and unhoused people were denied relief and even those who got a reduction still had to pay significant amounts, often equal to their monthly income; (2) the process is part of the punishment; often involving repeated court trips and dense forms and court bureaucracies with little to no flexibility or understanding; and (3) nothing on the back end erases the discrimination and trauma of a police encounter in the first place. As a result, this report’s recommendation is to reduce and eventually eliminate non-traffic enforcement.”

The state Legislature could do that next year.