I’ve long believed myself immune to “war on drugs” propaganda. Dr. Carl L. Hart’s new book, Drug Use for Grown-Ups: Chasing Liberty in the Land of Fear (Penguin Press), has persuaded me I was wrong.

My first encounter with anti-drug propaganda, at least that I can remember, happened around 1970, at age 13, in the form of an anti-marijuana film starring Sonny Bono. Even at that age, with no personal experience with cannabis and none of the knowledge of cannabinoid pharmacology that I acquired later, I distinctly remember thinking, “This man is an idiot.”

Years later, as a journalist covering the AIDS pandemic, I learned and wrote about how misguided drug paraphernalia laws created an HIV epidemic among drug injectors, and about the utterly bogus arguments used to stop sane workarounds such as syringe exchange programs. I wrote about the evidence that medical marijuana could help HIV patients and others suffering from pain, nausea and appetite loss, among other symptoms, and the relentlessly dishonest arguments the government was using against it as California and other states began legalizing medical use of cannabis.

That work eventually led to an eight-year stint as communications director at the Marijuana Policy Project, much of it spent in rhetorical hand-to-hand combat against government disinformation.

So I thought I was pretty well armored against anti-drug propaganda. But it turns out that I had still come to believe an awful lot spin, exaggerations and flat-out falsehoods—falsehoods that Hart, a Columbia University psychology professor who has published dozens of studies on the effects of drugs, systematically demolishes in Drug Use for Grown-Ups.

What kind of falsehoods? One that I’d completely fallen for was the claim that PCP—aka “angel dust”—commonly produces erratic, violent, dangerous behavior. Hart explains that published, peer-reviewed research firmly debunks this notion. Nevertheless, the “PCP makes users uncontrollably violent” myth lives on, and has been used to justify any number of police beatings and shootings, including the infamous 1992 L.A.P.D. beating of Rodney King, who was not under the influence of PCP, despite the cops’ claim they thought he was in order to justify their assault.

Decades later the claim of PCP-induced danger was used to excuse the Chicago police shooting of 17-year-old Laquan McDonald, whose behavior was described as scary enough to make the officers fear for their lives. Eventually police dashcam video, finally released under a judge’s order, completely shredded the official account of how the cop supposedly had to shoot him to protect himself. The officer was eventually convicted on multiple counts based on that video, but was let off with a shockingly light sentence, while his youthful victim had his reputation postumously trashed.

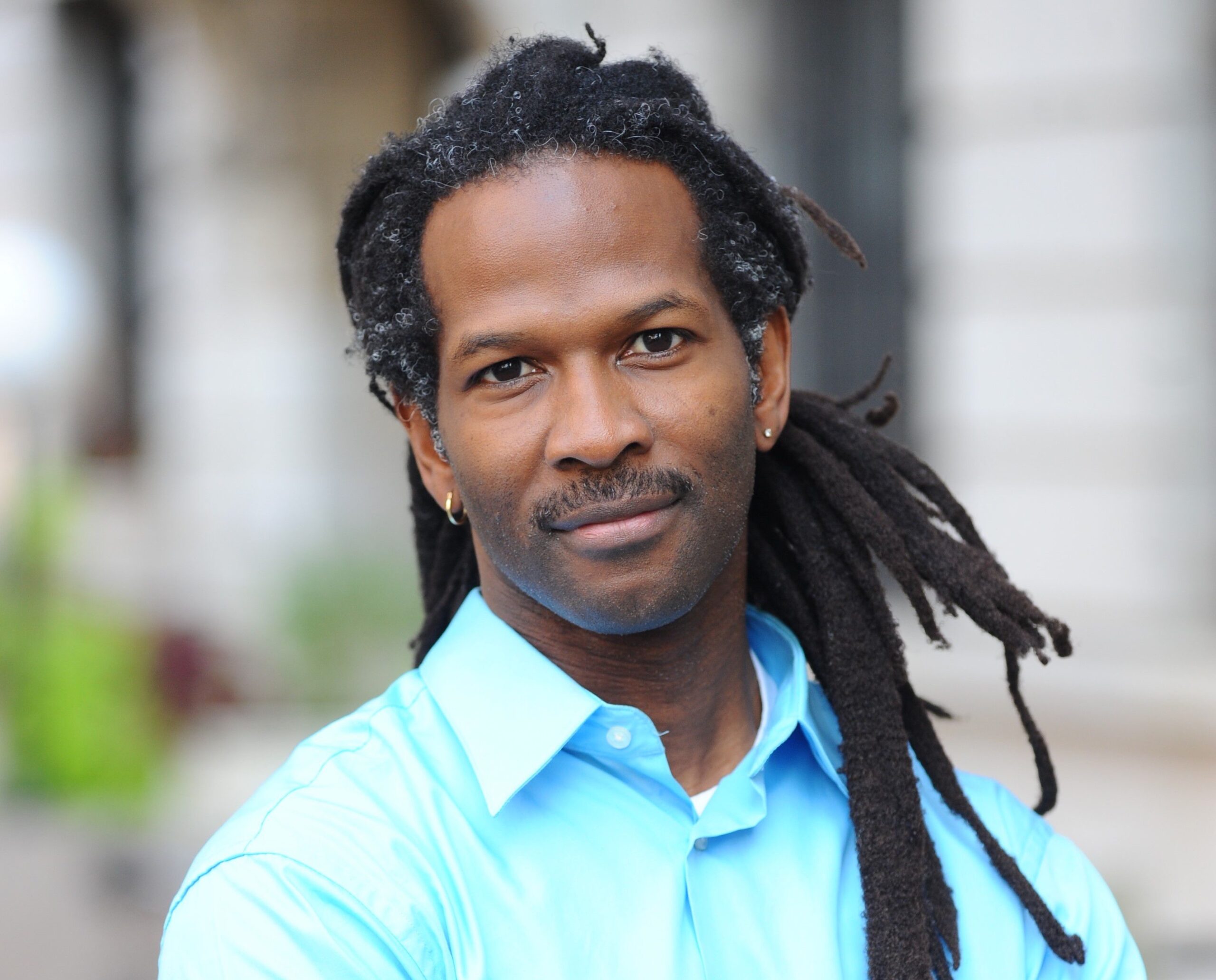

Hart rightly notes that these and many other incidents in recent years represent a continuation of the old “drug-crazed Negro” myth that has been used to justify draconian drug laws going back over a century. Hart, a Black man with dreadlocks who himself has been profiled (though, happily, not shot), doesn’t hesitate to call out the distinctly racist nature of the war on drugs or the failure of white reformers to fully embrace this uncomfortable part of the narrative.

Hart makes a convincing case that the dangers of many other substances commonly treated as highly addictive and lethal “hard drugs” have been wildly exaggerated, including heroin, methamphetamine and crack. “The fact is,” he writes, “that nearly 80 percent of all illegal-drug users use drugs without problems such as addiction.”

As for crack—the supposed “epidemic” that fueled Ronald Reagan’s massive escalation of the drug war—Hart writes, “I have given thousands of doses of crack to people as part of my research and have carefully studied their immediate and delayed responses without incident… Contrary to popular belief, the effects produced by crack are predominantly positive.” [emphasis added]

Hart also dismantles the standard narrative about heroin, painting a picture that will startle most Americans as much as it startled me: “All the evidence from research clearly shows that most heroin users are people who use the drug without problems such as addiction; they are conscientious and upstanding citizens.” Indeed, Hart maintains, the entire “opioid crisis” has been distorted beyond belief by politicians and the media.

Yes, some people do become addicted. And yes, overdose deaths represent a serious, tragic problem. But that problem, Hart maintains, is not due to opioids’ inherent risks. Rather, it stems from the extra dangers added by their illegality. Many overdose deaths—including an alarming recent spike in San Francisco’s Tenderloin—are traced to heroin contaminated with fentanyl. But fentanyl is not inherently dangerous; many people use it safely, both legally and illegally.

However, fentanyl is a lot stronger than heroin, and most buyers of street heroin, indeed most sellers of street heroin, don’t know exactly what’s in the product being sold, leading to deadly miscalculations by users. If people knew exactly what they were getting—as they would in a legal, regulated market—the problem of fentanyl overdoses would almost entirely disappear and thousands of lives could be saved.

Most non-fentanyl-related opioid overdoses come from mixing opioids with other sedatives, a problem that could also be alleviated in a legal market via appropriate labeling, package warnings and education. But such sensible solutions are effectively barred under prohibition because officials believe they would “encourage drug use.” In effect they think It’s better to let people die than to inform them that banned drugs can be used safely.

Put simply, we don’t have an opioid crisis, we have a prohibition crisis, one very much like the prohibition of alcohol in the 1920s, which sent deaths from contaminated booze into the stratosphere.

Much of Hart’s narrative is personal. He discusses and apologizes for his own role in spreading anti-drug hysteria in younger years. And he openly describes his own personal use of recreational substances, ranging from psychedelics to heroin. He unhesitatingly argues that drug use can be a positive good, that it can improve moods, open minds, and introduce users to beneficial experiences they otherwise would not have had.

Hart’s acknowledgment of his own drug use has been used by some in the right-wing media to try to discredit the book, but it no more undermines Hart’s credibility than it would do so for me, as a (mostly) responsible recreational user of wine to talk about how my drug of choice can be safely purchased in a regulated market and enjoyed in moderation without serious consequences.

Still, I wish Hart had acknowledged more plainly that he is far from the typical drug user. Even in a legal market with proper labeling and education, most drug users will never have the depth of knowledge of psychology and pharmacology that Hart has, which surely helps him anticipate and prepare for any unwanted effects.

Another small flaw: Hart rightly criticizes the media for sensationalist, inaccurate portrayals of drugs and drug users, but he misses the proverbial elephant in the room: Most journalists have been deceived by the very same propaganda he spends an entire book discrediting.

I experienced this firsthand again and again in my eight years as a professional marijuana legalizer: I regularly dealt with reporters who simply accepted that drugs are bad and that no legitimate “pro-drug” argument could possibly exist. It was rarely stated that boldly, but it was obvious in the way stories were framed and participants portrayed.

It was, in a sense, the opposite of the “both-sidesism” that rightly draws criticism in political reporting. Many reporters, editors, and producers couldn’t, and still can’t, conceive that there is another side to the argument, much less treat it as equivalent to the official voices telling us, “drugs are bad!”

That led lots of reformers, including me, to talk about harm reduction, and about how prohibition makes all the potential harms from drug use worse. That argument was and is factually correct, but Hart will have none of it. He wants us not only to reject prohibition, but to recognize that in a legal, properly regulated system, use of now-banned substances can be good for individuals and society. He has a point, if America’s lingering Puritan streak will allow us to see it.

Flaws notwithstanding, Drug Use for Grown-Ups is an important book, one that should be read by any official who goes anywhere near drug laws or enforcement policy. In particular, San Francisco officials currently plotting yet another futile crackdown on drug dealers in the Tenderloin should read it before they waste yet more tax dollars making things worse.

I ask gorn if the worst thing a ‘managed’ heroin user can do is nod out, why cannot the worst thing a ‘managed’ amphetamine user do is clean his house all night? True, too much amphetamine can lead to psychotic antisocial behavior, just as too much heroin leads to death. I think your prejudices are showing.

So much could be said, and expanded upon the subject of drug use.

The whys, the solution to deal with those that want to get off of them.

Portugal has successfully dealt with the drug issue.

The why: People turn to drugs for many reasons, but those that use it for pain whether emotional or physical stay with them. (Though this is still over simplified perspective.) First and foremost the pain needs to be addressed and dealt with.

The most valuable thing addressed in this article, I believe is making honest knowledge available. Knowledge is power, it gives the would-be user an informed perspective. A better equipped person is likely to do better than those going blindly into unknown territory.

Personally, I think drugs can be used beneficially to shift perspective from time to time, but the downside is forming dependencies and living numbed, thus missing out on life as it is (not exaggerated, suppressed, shifted, etc.) Because humans senses and imagination to create wonderful things without the aide of drugs. But they have to be trained and used, of else they atrophy.

Heroin can be managed over time through the provision of purity and dose metered supply along with clean needles.

Methamphetamine and cocaine, on the other hand, are only referred to in the same breath as heroin because they are criminalized on the same DEA schedule. The addictive profile of both substances, not to mention the corporeal health dangers of stimulant use at recreational dosages, require a different analysis.

The worst thing the junkie is going to do under managed addiction is nod out. The tweaker or coke head, on the other hand, by the nature of stimulants, is stimulated beyond the body’s specifications, and that results in all manner of behavior, much of it annoying or dangerous.

Acid, cannabis and shrooms are not problematic.

This is by no means an argument against legalization for harder drugs. It is a call to “unpack” the term “drugs” and consider each substance based on its pharmacological and addictive profile and to devise a public health response in anticipation of the downsides of each substance.