Fall film festival season is still a thing, as evidenced by Friday’s return of the American Indian Film Festival (which we’ll preview later this week) and, starting a day earlier, the 7th edition of SFFilm’s Doc Stories. Highlighted in this annual showcase for some of the year’s best nonfiction cinema is are two flashbacks to major events in African-American culture a half-century ago.

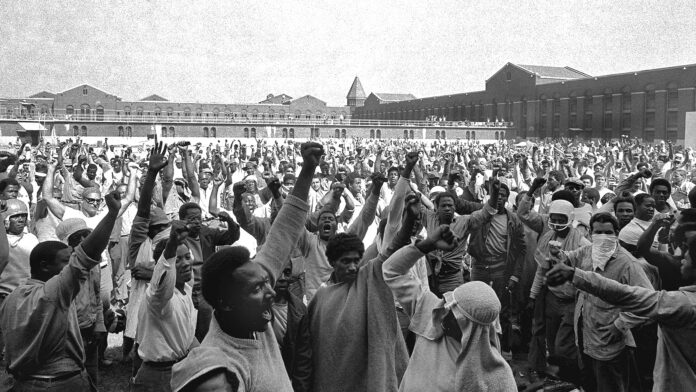

The opening night selection Thu/4 at the Castro Theatre is veteran documentarian Stanley Nelson’s Attica, which chronicles the 1971 prison revolt that remains the largest, most lethal such incident in US history. Inmates at this maximum-security facility near Buffalo, NY had been driven to that brink by miserable conditions, and abuse that often had a particularly racial slant, as a majority of prisoners were Black, but virtually all the guards were from all-white surrounding rural communities.

When tensions boiled over, the convicts took hostages for “leverage” in negotiating for “the basic necessities of being treated like human beings.” It could have been a watershed moment for institutional progress. But instead after four days the state, under pressure from the Nixon White House, wrested back control via an armed raid of State Troopers and National Guard that became an indiscriminate slaughter. While it was initially claimed that hostages were killed by inmates, evidence made it clear that the 43 dead (including ten civilian employees) were shot by their “rescuers” in the melee.

Nelson’s film has plenty of input from surviving ex-cons as well as lawyers,reporters and others involved; it also benefits from the substantial film/video records of what was a major national-media event. The director is expected to be present at this Doc Stories kickoff screening; Attica will premiere on Showtime two days later, Sat/6.

Also at the Castro will be musician Questlove with his directorial debut Summer of Soul, which had a successful theatrical run earlier this year. It resurrects long-neglected footage of the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival, a series of six outdoor concerts that offered a stupefying array of African-American musical talents including Stevie Wonder, Sly and the Family Stone, B.B. King, Mahalia Jackson, The Edwin Hawkins Singers, Nina Simone, Gladys Knight and the Pips, The Staples Singers, and many more. It plays Sat/6 at 8pm. The official festival closer on Sun/7 (also at the Castro) pays tribute to one more musical great: Dave Wooley and David Heilbroner’s Dionne Warwick: Don’t Make Me Over.

Other Doc Stories features, most both screened “in person” (at the Castro or Vogue) and available for streaming, include features about China’s economic explosion (Ascension), US homelessness (Lead Me Home), refugees around the globe (Simple as Water, Flee), Texas adolescence (Cusp), COVID (The First Wave), and Australia’s recent “Black Summer” of catastrophic fires (Burning). There will also be a program of short New York Times Op-Docs, a free showing of culinary bio Julia (as in Child), plus an array of free online talks and panels. For complete program, schedule and ticket info, go here.

Even aside from Doc Stories, it’s a busy moment for nonfiction features. This Tues/2 sees the On Demand release of Jacob Morrison’s River’s End: California’s Latest Water War. While it briefly covers recent droughts and historic long-distance diversions of water to So. Cal. (famously dramatized in Chinatown), the focus here is on unsustainable current practices and future threats. You might be surprised to learn that agriculture uses 80% of water in California (as well as many other states), yet contributes much less to the Golden State’s economy than one would expect.

Worse, a great deal of that water goes to crops (notably water-hogging almonds) that are far from food necessities, and in any case are largely grown for export markets. But even that dominance may be severely curtailed by the rival needs of an ever-growing Greater Los Angeles. This complex overview may bring in a lot of new-ish factors, like climate change and species extinctions… but some things remain the same, notably corrupt relationships between California politicians and industry lobbies.

LA is also the setting for Wu Tsang’s Wildness, a 2012 documentary feature that can be streamed for free throughout November as one of the last things to be shown by SFMOMA’s historic, shamefully soon-to-be-terminated film/video program. It focuses on the Silver Platter, a corner bar near MacArthur Park that’s existed since 1963. Over that long span it’s been home to a shifting roster of patrons, most recently the Latinx LGBTQ community, and in particular a vibrant (if rivalrous) subset of trans emigres from Central America.

The feature chronicles a moment of cross-pollination in which largely straight “gringos of every shade” start a weekly club night that’s more of an art/punk/DJ/ performance art scene than a drag-show one. But its success ultimately proves more a threat than a boon for “los chicas,” who don’t need the competition—or the attention from Immigration authorities. This is an object lesson in good intentions, culture clash, and the fine line between inclusion and gentrification. Wildness can be accessed through Nov. 30 here.

Some of the protagonists in that film say they fled homelands where people like themselves were openly persecuted, not least by law enforcement. Curiously, the Mexico City police officers in Alonso Ruizpalacios’ A Cop Movie protest a couple times that their hands are tied in dealing with such minorities, even when an abusive drunk at a Gay Pride celebration pointedly urinates in public. Still, it’s all good for the “Love Patrol,” as 30-ish duty partners Teresa and Montoya get called once their off-duty romance is sussed out.

Well, good to a point: Much of this film is taken up with questions of police corruption, ethics and bribing. Perversely, the couple run into trouble when trying to actually enforce the law on a citizen who (being a politician) expects to be exempted. They’re punished not for corruption, but for not respecting the established lines of corruption.

A Cop Movie is something considerably more complicated than a mere ride-along expose, however. Somewhere past its midpoint, the film makes clear what it had already hinted at, that we are watching actors playing real people. We then see those actors preparing (often neurotically) for their roles, which includes ride-alongs with the real-life “Love Patrol.” Such tricksiness may make more sense to Mexican viewers, for many of whom a fraught, absurdist, ironical stance toward police is perfectly natural.

While I wasn’t entirely sure this experiment worked, it’s certainly interesting, and offers further proof that Ruizpalacios is one of the most fascinating directors to come along in Mexican cinema in years. His prior, marginally-more-conventional features Gueros and Museo are well worth a watch. A Cop Movie (which played limited U.S. theaters last week) premieres on Netflix this Fri/5.

Also straddling fact and fiction is Snakehead, the first narrative feature by documentarian Evan Jackson Leong (Linsanity). Sister Tse (Shuya Chang) pays to be smuggled to the US from mainland China under harsh conditions, willing to do almost anything to be reunited with the child she was forced to give up years earlier. But she is not willing to pay off her debt via prostitution; her drive and resourcefulness attract interest from Dai Mah (Jade Wu), the NYC Chinatown-based power broker who presides over human trafficking and myriad other interconnected black market enterprises. But as Tse rises in that syndicate’s pecking order, she earns the ire of Dai Mah’s son, the all-too-tellingly-named Rambo (Sung Kang), a hotheaded ex-con.

Snakehead is well-crafted, and will shed some light for viewers on the complicated criminal webs that crisscross the world between the US and China. But it’s also rather hamfisted, sensationalistic, and predictable as a violent melodrama—seeming particularly so if you’ve read Say Nothing and Empire of Pain author Patrick Radden Keefe’s prior The Snakehead: An Epic Tale of the Chinatown Underworld and the American Dream. It tells the true story of “Sister Ping,” the real-life model for Leong’s fiction, and the mind-bogglingly vast shadow empire of business she’s presided over for years (even while in prison). The film is a good introduction to the general subject, but it pales beside the book’s neck-deep inquiry. Snakehead is currently playing the Vogue Theater in SF, and is also available on Digital and On Demand platforms.

If all the above offers a little too much reality for your needs at present, the week also brings a couple titles of contrastingly stylized, eccentric interest for hardcore arthouse cinephiles. One is Labyrinth of Cinema, the final film by idiosyncratic Japanese director Nobuhiko Obayashi, who died last year at age 82. He is best known in the West for 1977’s House, a dementedly over-the-top supernatural thriller that belatedly found cult status abroad. But that represented just one extreme end of a prolific ouevre that spanned from experimental shorts to TV commercials, from earnest teen dramas to the penultimate work of an epic antiwar trilogy released between 2012-2017.

Labyrinth is more of a parting funhouse/footnote, a phantasmagoria in which people at a movie house step in and out of the projected celluloid fantasies—which encompass every genre from samurai and yakuza action to musicals, period ghost stories, sci-fi, animation, et al. But once again, war (and particularly WW2) is the principal thematic focus. A manic three-hour mashup of green screen FX and every other trick in the book, it manages to be a history of the world, of Japan, and of cinema itself, an entity both playful and exhausting. The Roxie currently has it scheduled for three shows, one each on Thu/4, Sun/7, and Tue/9. More info here.

Comparatively short, sharp and disciplined by contrast is Chess of the Wind, a 1976 Iranian film by documentarian Mohammad Reza Aslani that was basically thought lost for decades. That is, until film negatives were miraculously found in an antique shop (then smuggled out of the country) six years ago. The movie was originally screened once at a film festival, then banned, its outre content doomed to disfavor after 1979’s Iranian Revolution swept in a far more conservative cultural climate. But this is not the tacky, escapist commercial cinema commonly associated with that pre-revolutionary era. Instead, Chess is a Little Foxes-type grand guignol of ruthless power struggles within a wealthy family, delivered in a coldly elegant style worthy of Visconti or Fassbinder.

A wheelchair-bound woman (Fakhri Khorvash) is heir to her late mother and father’s fortune, yet treated like dirt so long as the household is ruled by her brutish stepfather (Mohammadali Keshavarz). When he is taken out of the equation, happiness remains elusive—not just for fear his corpse might be discovered by the police, but because relatives and servants alike all have their own schemes to seize control.

Despite its formal compositions and lack of graphic content, Chess has plenty that shocks, including one very surprising lesbian scene, as well as all kinds of grotesque melodrama, including a climax lit so it appears to take place in Hell. it took the director 32 years to make a second narrative feature (still his last, to date), but this striking rediscovery belatedly gives him a prominent place in the annals of Iranian cinema. Chess of the Wind plays BAMPFA’s Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley this Thu/4, and also Sun/21, both at 7pm. More info here.