With one more 2023 production left and 100 years of work behind them, the start of SF Opera’s “new century” has been less of a marathon or even a sprint, but more a long jog attempting to recover from stumbles. There have certainly been high points, such as new music director Eun Sun Kim bringing a skilled touch to the lauded orchestra. Similarly, the talented performers and tech crew have outright dazzled with German Expressionist design and some truly passionate performances. Yet, the company’s 101st year has also been defined by awkward revivals of controversial classics (Madame Butterfly) and new operas that work better in concept than execution (The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs).

Omar (Bay Area premiere through November 21 at the War Memorial Opera House, SF), by composer-librettist Rhiannon Giddens and co-composer Michael Abels, is closer to the latter, though not nearly as campy. On the surface, the duo’s opera couldn’t be more timely: the empathetic portrayal of Muslims is something desperately needed now, when world powers grotesquely celebrate the destruction of an Arab Muslim country (Palestine) as it’s razed by Israeli colonizers. Furthermore, telling an otherwise unsung (no pun intended) chapter of history—one relating to slavery in the US—is not only bold but necessary.

The problem is that Giddens, who also serves as librettist, never once makes Omar ibn Said into an actual person. The figure shown here is a walking-talking plot device; someone to whom things happen rather than someone in whose shoes we can see ourselves. Even a book-ending device of having US tenor Jamez McCorkle change from casual wear to his “Omar” attire ultimately goes nowhere.

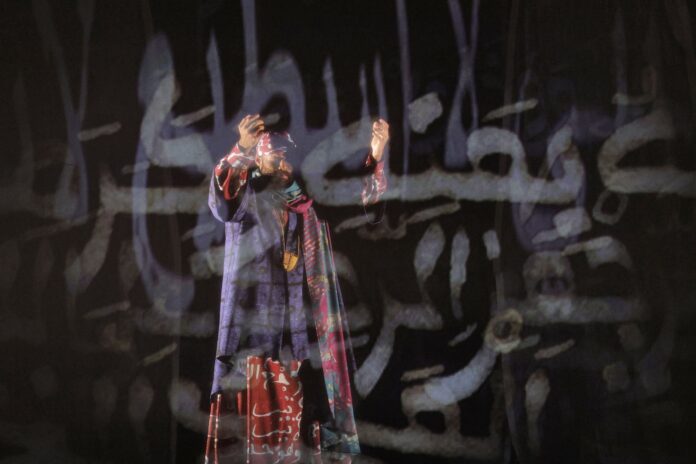

Our story begins in Futa Toro, Senegal in 1807. Omar is a devout Muslim scholar who has dedicated his life to the study of the Qu’ran (creatively shown with a transparent projection screen on stage, making it appear as if Omar is writing words that float on air). He’s at odds with his brother Abdul (US baritone Norman Garrett), who bends over backwards to justify trafficking in slavery in order to be “left alone” by “them” (presumably European colonizers). Omar confides in his mother Fatima (US mezzo Taylor Raven), who just wants her boys to stop fighting one another. Before we know it, Abdul frantically announces he was betrayed by his new friends, their village is raided, Fatima is killed, and Omar is put on a slave ship headed across the Atlantic.

The slave ship sequence shows just how much of a missed opportunity the libretto is. It begins with Omar desperately trying to communicate with fellow enslaved people to figure out just where he’s going, but almost none of them speak the same dialect. It’s a Kafkaesque nightmare that uses psychological terror in place of graphic violence: very effective. But when the ship lands in Charleston, the music accompanying the slave auction goes from the dramatic jazz of previous scenes to something that sounds too much like “Herod’s Song” from Jesus Christ Superstar (and that’s indisputably the worst part of Jesus Christ Superstar).

What’s more, the verbalizing up to that point had all been in the traditional European pronunciations one expects from opera, but when characters like Charleston slave Kate Ellen (US mezzo Rehanna Thelwell) begin speaking in US Southern twangs, it clashes with the Euro style like oil meeting water.

Then there’s the aforementioned fact that none of the characters are fleshed out, least of all Omar—odd, since he is attributed as having written one of the few autobiographies by an enslaved US person. He spends the show walking from stage area to another just as he seems to go from one master to another. He’s shows as isolated for not knowing any English, then suddenly does out of nowhere. A scene in which one master (Canadian bass-baritone Daniel Okulitch) vows to “break” Omar—seemingly a callback to the “Toby” scene from Roots—rings hollow as Omar acquiesces immediately.

And so many other characters come in and out of Omar’s life that none of them linger. A little white girl (US mezzo Laura Krumm) seems drawn to Omar at an auction and insists her father buy him, but we never see the girl again, begging the question as to what the point of that was?

For all the cast’s strong performances and Amy Rubin’s interesting set design, nothing connects. The story includes slavery, religious oppression (Christianity is pushed onto the enslaved people), and the quest to reclaim one’s humanity, but the show doesn’t actually do anything with those elements. It’s hesitant to even hold the US or white supremacy accountable for evils of slavery, and is far too dismissive of how the white characters react to a slave being able to read and write. It even seems to hand-wave the suggestion that a “master’s friend” is probably raping enslaved women. Those aren’t subjects to be taken lightly; if you’re going to include them in your story, you have to cover them completely and correctly, or don’t cover them at all.

I also found myself confounded by the costume designs by April M. Hickman and Micheline Russell-Brown. They aren’t bad, per se, but most are long robes with large writing on them (eg. Omar and his family have Arabic lettering; most of the white characters have English cursive). It makes sense for Omar’s trade back in Senegal, but it doesn’t quite fit with anyone or anything else.

As I watched this via livestream, there were no CO² readings for me to take in person. I will say that I saw only a handful of patrons masked in the lobby footage shown pre-show and intermission.

It’s tempting to say that Omar is an opera that treats the enslavement of Black people with kid gloves, but even that seems too kind. It seems to strive for a magical realism, but gets far too hypnotized by its own pretty colors. Most of the performances are as great as you’ve heard, but the libretto is yet another stumble at the start of SF Opera’s nascent new century.

OMAR’s Bay Area premiere runs through November 21 at the War Memorial Opera House, SF. Tickets and more info here.