This week brings a clutch of special filmic events, from a couple long-running festivals to spotlights on animation and cinema of the Caucasus.

The most historied among them is the American Indian Film Festival, the world’s oldest and largest of its type, now in its 47th year. (It actually started in Seattle before making a permanent move to SF in 1977.) Casting a wide net, with high-profile annual awards, its prize-winners over the decades have encompassed such influential titles as Powwow Highway, Dances With Wolves, Incident at Oglala, Smoke Signals, Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner, and Wind River.

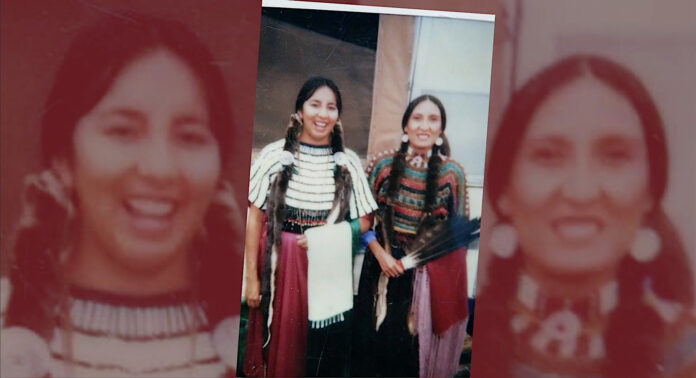

This year’s program, showing Nov. 4-12 at various SF venues, opens Friday at Letterman Digital Arts Center in the Presidio with a trio of works sharing a Northern California theme. Yvan Iturriaga’s Unlord the Land is a short dramatic narrative about community loyalty vs. gentrification in Oakland, written by born-and-raised Tommy Orange of the novel There There, a 2019 Pulitzer finalist. Shaandiin Tome and Rayka Zehtabshi’s short documentary Long Line of Ladies offers a sweetly affirming view of a traditional coming-of-age ceremony for girls that is being revived after a long hiatus by the Karuk peoples of our state’s far north.

The feature-length IndianLand looks at the signature event of the so-called Red Power movement of half a century ago: The 19-month (from November ’69 to June ’71) occupation of shuttered prison island Alcatraz by Native activists protesting the never-ending injustices against tribes by the US government, particularly in the realm of land seizures. It galvanized international media and public attention to those issues as perhaps nothing had before (or has since), putting pressure on Federal policies and resulting in some real, positive change. Liz Irons’ documentary chronicles this memorable chapter both in plentiful archival materials and in the recollections of many surviving participants who reunite for an extensive 50th-anniversary commemoration.

AIFF’s official closing selection on Thurs/10 (there are additional events the following two days) is writer-director Myles Clohessy’s The Redeemer, a period western starring Irene Bedard (the voice of Disney’s Pocahontas) in which two Native women struggle to survive after being kidnapped by roving outlaws. Brandon Routh and Chris Mulkey also appear in this thriller about the darker side of the “Wild West.”

In between, the festival’s seventeen individual programs feature a wide range of tribal representation onscreen (and behind the camera), as well as spotlights on music,animation and sci-fi ; environmental, historical, political and youth issues; and much more. For full program, schedule and ticket info, go to www.aifisf.com.

The 8th year of SFFilm’s Doc Stories has a bit of thematic overlap in Jesse Short Bull and Laura Tomaselli’s Lakota Nation vs. United States, about a long, bitter battle over control of sacred lands in South Dakota’s Black Hills.

Elsewhere, this annual nonfiction cinema showcase otherwise charts a diverse gamut of subjects: Portraits of an artist (All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, about photographer Nan Goldin, plus the self-explanatory Louis Armstrong’s Black & Blues) and of a cultural phenomenon (Mickey: The Story of a Mouse); political turmoil in the perpetually roiled Afghanistan (In Her Hands); climate change (as viewed through All That Breathes’ urban animal sanctuary/veterinary in polluted, sweltering Delhi); and incarceration (Sanson and Me, another adventuresome mix of doc and staged elements from Rodrigo Reyes of last year’s striking 499).

While these films roam the globe, Doc Stories’ opening and closing features are very much California tales. The world-premiering Jerry Brown: The Disrupter is bookended by annoying sequences in which director Marina Zenovich pretends to be exasperated by our ex-governor’s reluctance to provide sound-byte responses to the kinds of vague-generalization questions no intelligent person likes to answer (“Describe yourself,” “Are you happy?” etc.).

In between, however, we get a sound overview of a long, complicated, often controversial political career that started off both benefitted and hobbled by the subject being offspring to another Gov. Brown (Edmund) some consider “the father of modern California.” From seminary dropout through Yale law school to Secretary of State and onward, his son hewed a path both privileged and stubbornly resistant to the entrenched customs of power. (Notably, among interviewees here, GOP ex-guv Schwarzenegger offers high praise across the aisle, while fellow Dem Willie Brown snarks—but then Jerry, always critical of corruption, might have a few choice words for the latter in return.)

In his first two terms leading the Golden State, an under-40 Brown greatly diversified cabinet representation, worked closely with Cesar Chavez, and was a prescient advocate for renewable energy long before the term “climate change” was on anyone’s tongue. Yet Prop. 13, the “Governor Moonbeam” tag, and other factors (not least the first of his three ill-advised Presidential campaigns) ultimately made that run look like a failure. After a stint (mostly) out of politics, he returned as mayor of Oakland, as state Attorney General…and then as governor for another eight years, during which span he pragmatically eradicated the budgetary deficit. This admiring portrait may not be “warts and all,” but it does justice to an increasingly rare sort of U.S. political figure, one who’s eschewed empty rhetoric and been willing to publicly admit it when proven wrong. The director and subject (who was born in SF) are expected to attend the Vogue Theater premiere this Thurs/3.

The closing nighter, which was unavailable for preview, is another tale of father-and-son high achievers. Sr. from American Movie’s Chris Smith is about Robert Downey—not the Iron Man movie star (though his company produced it), but his NYC-native dad, who passed away last year. That Downey was a notable participant in the antic, freewheeling independent U.S. cinema of the 1960s, culminating in 1969’s advertising satire Putney Swope. Its critical and commercial breakthrough would not recur for him as he and Hollywood tried to get along, but his later films all retained some idiosyncratic appeal. The director and Downey Jr. will attend the Castro screening on Sun/6. For full Doc Stories info, go here.

With ten diverse titles in just ninety minutes, the 22nd Annual Animation Show of Shows offers a de facto film festival in a single sitting. Back after a two-year COVID hiatus, this collection returns with full runs starting Fri/4 at Oakland’s Parkway and the Lark in Larkspur, plus single showings at Rafael Film Center (Wed/2) and SF’s Roxie (Tue/8).

As usual, it offers an international gamut of techniques and tones, narratives and abstractions, including recent works from France (Empty Places, Zoizoglyphe), Germany (Good and Better), Japan (Beyond Noh), Poland (Rain), Switzerland (Average Happiness), Iceland (Yes-People), Russia (Ties) and the U.S. (Aurora). The best (and by far longest) is saved for last: A 4K restoration of Frederic Back’s 1987 Canadian Oscar winner The Man Who Planted Trees, a lovely parable in hand-drawn pastels adapted from a story by French author Jean Giono, narrated by Christopher Plummer. For info on all the current Show of Show’s shorts and playdates, go here.

Finally, BAMPFA has just started a month-long Georgian Cinema series that highlights holdings from the Archive’s own collection. We don’t mean Georgia the southern state—though it has actually become a major player in commercial film production during recent years, thanks to tax incentives. (Though the state’s increasingly reactionary politics have been steadily dulling that financial allure for Hollywood.)

No, this is the former Soviet territory that reclaimed its independence in 1991, and is currently irking the Kremlin by having applied for EU membership shortly after Vlad’s invasion of the Ukraine early this year. (It was already working towards that status with NATO.) Because production was so controlled by Moscow for decades, Georgian filmmakers have often simply been lumped in with the Russians, particularly as they frequently had to train at the same schools, and kowtow to the same bureaucrats. But many among what we think of as classic Russian films and their directors are in fact Georgian, from silent comedy favorite My Grandmother to Cold War era visual wizard Mikhail Kalatozov (I Am Cuba).

The current series began last Saturday with Otar Iosseliani’s 1975 Pastorale—an ideal illustrative case, in that its gently satirical snapshot of village life (anticipatory of The Band’s Visit) was nonetheless too provoking for Soviet authorities, who shelved it. When it was finally seen at the Berlin Festival in 1982, its success convinced the director to move abroad, where he found considerable artistic freedom and acclaim before finally returning home. Similarly angled if more nostalgic in bent is Tengiz Abuladze’s 1963 Iliko, Illarion, Grandmother and Me (playing Sat/5), a sunny, episodic reminiscence of rural youth. Two decades later, that director would later shock everyone with Repentance, an acid sendup of Stalinism’s cruel absurdities, which was itself banned for a pre-years.

A contrastingly stark, primeval mysticism permeates several other features here. Abuladze also made 1967’s Molba aka The Plea (Sun/13), a striking period tale of Christian vs. Muslim tensions in a remote mountainous region. Based on verse by national poet Vazha-Pshavela, it is itself a kind of poem—with monumental B&W imagery, a superb orchestral score, traditional songs, and characters’ inner thoughts expressed in voiceover rather than dialogue. A similar if more lyrically diffuse effort is Aleksandr Rekhviashvili’s 1981 The Way Home, which also deploys poetry (by Bella Akhmadulina), but bows to Pasolini in its allegorical pilgrimage structure. Ostensibly about an actual 18th century theologian, it occupies some timeless netherland between regional history, folklore and parabolic mystery play.

Closer to straightforward biopic is the 1969 Pirosmani, whose director Giorgi Shengelaia was so absorbed by the subject, he made documentaries about it one decade earlier and two decades later. Avtandil Varazi plays the titular figure, a self-taught painter who (not unlike Van Gogh) found little appreciation in his rather hard, impoverished life, but whose work became celebrated posthumously. Shot in somber color, the film’s compositions have the evocative simplicity of Niko Pirosmani’s canvases. Arguably the most famous Georgian director of all, Sergei Parajanov (Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors, The Color of Pomegranates)—who was particularly victimized by Soviet minders, including years in prison—also weighed in with 1985’s Arabesques on the Pirosmani Theme. One of his last projects, that short pays homage with a mixture of the artist’s original images and the director’s own characteristic tableaux.

There are a handful of more recent Georgian films in the series, from 2011 documentary Will There Be a Theatre Up There?! (about one of the nation’s most popular actors) and brief 2009 satirical narrative Felicita, both on Sat/12, to Nov. 27 closing selection Susa. Rusudan Pirveli’s 2010 feature is a bleak, minimalist glimpse of a 12-year-old in a backwater who already seems to be shouldering all the miserable adult obligations in the world. Its color palate is at once delicate and murky, like our young hero’s status quo—not to mention his near-hopeless prospects. For full into on Georgian Cinema: Highlights from the BAMPFA Collection, go here.