The life of acclaimed literary artist and civil rights activist Dr. Maya Angelou, who died at age 86 in 2014, can be viewed from multiple perspectives.

It is a tale of pain, pathos, oppression, and a struggle to achieve liberties due primarily to being a Black woman establishing her rightful place while living in America’s white male-dominant society. Alternatively, Angelou can be held up and revered for embodying Black beauty, women’s strength, literary brilliance, scholarly excellence, astonishing determination, honesty simultaneously succinct and loving. The unquenchable, joy-filled human spirit of her work continues to galvanize generations who follow in her footsteps and rise up against powerful forces arrayed against them to emerged in a life triumphant.

Now, a public art monument created and erected to honor Angelou’s legacy mirrors her lifetime’s trajectory and reflects her complex journey—as does the troubling but eventually triumphant story of the monument itself.

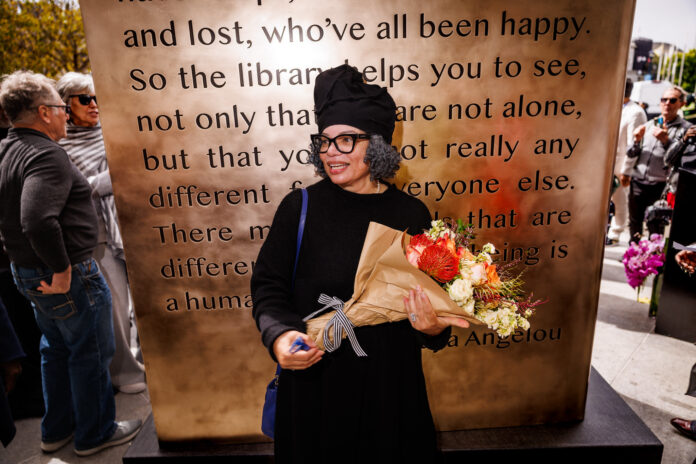

In 2018, the City of San Francisco passed an ordinance to increase the representation of women in public art to 30 precent, and began the process by commissioning the first artwork in its Civic Art Collection dedicated to a Black woman. “Portrait of A Phenomenal Woman,” the monument created by multi-disciplinary artist Lava Thomas, had its public unveiling in September and stands just outside the Larkin Street entrance to the San Francisco Public Library’s main branch.

Crafted in book form, Thomas’ portrait of Angelou and “Still I Rise” adorns its “front cover,” with a longer quote from Angelou about the vital importance of reading, knowledge, and libraries on the back. The installation represents a milestone for the city. The nine-feet tall, roughly 6,900 pound bronze monument is a visible declaration of healing, empowerment, and justice in the face of a pubic art journey that included segues into erasure, racial bias, ignorance, opposition, and oppression.

Like light and dark scenes leading to a final chapter in a book with a celebratory ending, the process began in November 2018 with 111 artists responding to a call for proposals. Three finalists, Thomas among them, were invited to present formal proposals. Briefly summarized, events after Thomas was selected included acceptance of her design, city officials rescinding acceptance, national and local media attention, lengthy Visual Arts Committee meetings open to the public (comments largely supportive of Thomas and criticical of process), and eventually, apologies to Thomas from Commission President Roberto Ordeñana, then Mayor London Breed and other city officials.

The commission to Thomas was re-offered, she at first declined, later decided a larger statement could be made, and chose to accept the commission. IN the wake of all this, the City pledged clearer guidelines and increased diversity on the committee and in public art that includes not only Black women but other inadequately represented people.

Without saying complete justice is served or “what’s done is done,” Thomas and almost everyone involved have shelved that chapter and shifted to more positive narratives. Centered on reading, libraries, and public art’s value and potential to create social and cultural change, the messages are grounded in Angelou’s courage, integrity and legacy and Thomas’ civic and social justice activism.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

Thomas’ artistic practice spans drawing, painting, photography, sculpture, and site-specific installations. Steeped in what a website bio describes as “her family’s Southern roots, current and historical socio-political events, intersectional feminism, and African American protest and devotional traditions,” Thomas’ artwork is exhibited or retained in the permanent collections of numerous major art museums and galleries worldwide.

Replying in an email to interview questions, Thomas repeats a reference to the process as an “ordeal,” and says, “As I said before, it was trying at times, but who escapes this life sans trial? The monument is built on those very principles—justice, integrity, and courage. For me, completing the monument isn’t just about the physical structure; it’s about what it represents. Yes, the monument is a triumph in itself, but the real victory lies in the fact of creating something bigger than ourselves. Changes to the process of approving public art were important, but the ultimate goal was to honor Dr. Angelou in a way that reflects the integrity of her legacy.”

The choice to use bronze, a material she says “stands the test of time,”was intentional. The large scale is bold and reflects Angelou’s weighty contributions. “It’s about creating a presence that feels as solid and enduring as the values she stood for. The texture, the weight—everything about it speaks to resilience and strength, while also inviting people to reflect on the monumental impact of learning, literacy, and self-expression.”

The portrait drawn by Thomas is based on a still image from a 1973 interview of Angelou in conversation with Bill Moyers. Her short Afro is a symbol of Black pride, identity, and empowerment; the hoop earrings a respectful acknowledgment of Black womanhood. Thomas says both elements speak to Angelou’s grace, unapologetic boldness, Blackness, and elegance. “It was the embodiment of her freedom and self-sovereignty.”

During the six-year saga, Thomas discovered greater measures of her own integrity, strength, and the power of perseverance. “Dr. Angelou once said, ‘I have to answer to myself,’ and that resonated deeply with me. Throughout this journey, I’ve had to ensure that I was conducting myself in a way that would make both her and myself proud.”

Public, and all art, according to Thomas, holds potential to establish space for truth and spark conversations that challenge existing narratives and give voice to the silenced. The monument is a tribute to one Black woman, but also calls out for thousands of untold stories and long overlooked or never heard voices to be seen, listened to, shared, and celebrated.

Noting that artwork is not meant for isolation but exists in community, and is most animated when shared and allowed to reshape world views, Thomas says if she could be in conversation with Angelou today, she would ask about quiet strength.

“So much of her life was lived in the public eye, but I imagine her most powerful moments came when the world wasn’t watching. I would want to hear her reflections on how she found peace amidst adversity, and how she managed to transform her pain into such beautiful art. Most of all, I would just want to listen to her wisdom, her humor, and her strength—soaking in the knowledge of a woman who redefined what it means to be free.”