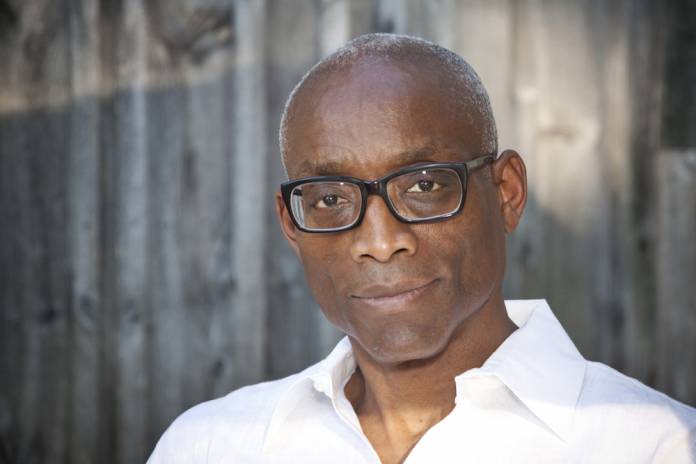

ONSTAGE “I certainly don’t mean to talk your ear off,” Bill T. Jones, one of the legends of contemporary dance and queer culture, says over the phone as he rockets through the city in his husband Bjorn Amelan’s car. But I could listen to Jones’ fabulously oaky eloquence for hours, especially as he expounds on his latest projects and our present political and artistic moment. He’ll be speaking Sunday, January 22 at the JCC’s Arts and Ideas series in San Francisco.

Jones, who formed his renowned dance company Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance with his partner Zane in 1983, revolutionized dance by choreographing from a place of identity and the quest for self-representation, speaking out about marginalized experience, especially his own as a black gay man. He became synonymous with the downtown New York arts scene, although he and Zane were also former San Francisco residents (Zane died of complications of AIDS in 1988).

Jones still comes out once every two years or so to visit his sister, performance artist Rhodessa Jones. Besides his JCC talk, Jones is out here working on a collaboration with local writer Marc Bamuthi Joseph, who’s writing a libretto with Haitian-American composer Daniel Bernard Romain for a hybrid opera called We Shall Not Moved that Jones will direct.

Jones’ current NYC artistic base is New York Live Arts, a merging of his dance company with the historic Dance Theatre Workshop. Among the many, many things going on there is a humanities program, which in 2017 will be curated by beloved Bay Area “transgenre” performer Justin Vivian Bond.

As befits his appearance at the Arts and Ideas series, Jones, in our brief but lively conversation, was bursting with both — including a few surprising opinions on the state of liberal politics and contemporary dance from one of the “architects of identity politics.”

48 HILLS The Arts and Ideas series is very wide-ranging. What will you be speaking about in your talk there?

JONES I think it will be about empathy, and time. It will be focused on the trilogy of work I’m doing right now. We’ve shown the first two sections of it. The trilogy is called ‘Analogy’ — as you know analogy means a comparison of two or more things. These are all built around entities or personalities close to me.

The first one is my husband Bjorn Amelan’s mother, Dora — a Jewish woman born in Stasbourg who was 19 when the Second World War broke out. We hear from her about what it was like to work at internment camps in the south of France. it’s a very lovely portrait of a young, great woman. Hers is called ‘Analogy/Dora: Tramontane.’ Tramontane is the wind in the south of France that she describes as she was working on this arid plane in the internment camps, one called Rivesault and one called Gurs. She was there working with people, many of whome ultimately were deported to Auschwitz and so on. Members of her own family were deported. Bjorn and I, who have been together 24 years, we both marvel at her stories and her life.

The second one is even more personal. It concerns the child of my sister, his name is Lance Theodore Briggs, or LTB. He lived in San Francisco during his formative years, a handsome young dancer, model, who was at the School of Ballet when he was very young, got involved in the sex trade, drugs, and although he kept having a career — he’s got an unbreakable body, the things he’s done to it — he is now a man paralyzed from the waist down.

He and I started doing an oral history three years ago, and I told him I wanted to make a work mirroring Dora’s work. He and I are two black gay men trying to speak honestly about our generational differences and the dysfunction that has informed our relationship. It’s very strong, driven by a sense of love — or at least a desire to love.

The third section is one that I’m working on now that will be premiered at the American Dance Festival, in June-July, and this character is actually a quasi-novelistic character coming from a great novel by W.G. Sebald. This is from the third of the four novellas which is from The Emigrants, and Ambrose is a working class German who came to this country just before the First World War. He is a mysterious man, who escapes his small town in Germany to work in grand hotels, having liaisons with mysterious personalities, living for a while on a floating house on a lake near Kyoto with a Japanese “unmarried” diplomat.

He then is hired by the Solomon family, a very wealthy Jewish family on Long Island. He’s been hired to be the manservant-companion-guardian of their dissolute, eccentric son Cosmo Solomon. And the writer treats this relationship with great delicacy and mystery. The family says that Abrose is of the “other persuasion” but they never go into what they meant. So he is the subject of the last section, which is called ‘Analogy/Ambrose.’

Every one of those stories to me is about a hidden life, and in some ways is about the question, “What is a life worth living?” And empathy — they are all exercises of empathy, and that will be my starting point for my talk at the JCC.

48 HILLS I write about nightlife, and a lot of club people were excited about part two, Analogy: Lance. It’s a spectacular-looking journey through contemporary nightlife, including hip-hop and vogue balls. It’s very evocative of the nightlife of the 1990s, especially. Did you draw on any of your own nightlife experience for this part?

JONES Oh no, no, I’m another generation entirely. At the time of life I describe with Lance, which for me would be the early 1970s, Arnie Zane and I were living on Potrero Hill here in San Francisco, on Rhode Island Street, and we were into exploring Krishna consciousness. I mean I’ve done my time at the bathhouses, I maybe did a turn a bit on the floor. But I’m very much from the counterculture.

But my nephew who always looked to me as an example of what the dance world was — I don’t think he ever really understood the type of avant-garde concert dance that I did. He knew that his uncle was a famous dancer, and he wanted to be like that. His take on that was pop music and clubs. I would have less problem with it if somehow club dance were more informed. If it had a kind of critical distance. But it was one big party. And there was the ever-present specter of drugs. And he’s wondering why his career never took off, and how he ended up flat on his back. And he’s been on his back for two years. Now in a wheelchair at least — so there is a kind of hopeful end to it.

48 HILLS You speak of empathy. Out of all the artists who’ve explored identity and the crossroads of being, art, power, politics, and economics, I think a lot of people are looking to you, and feel that right now we’re in a moment where we need these expressions more than ever …

JONES Oh you think so? You don’t think it’s a huge moment of mea culpa that identity politics folks are going through after the last election? People saying we spent all this time on talking about what bathrooms to use when we should have been talking to the disenfranchised poor white people in the Midwest rust belt, we should have been talking about what “other” lives matter?

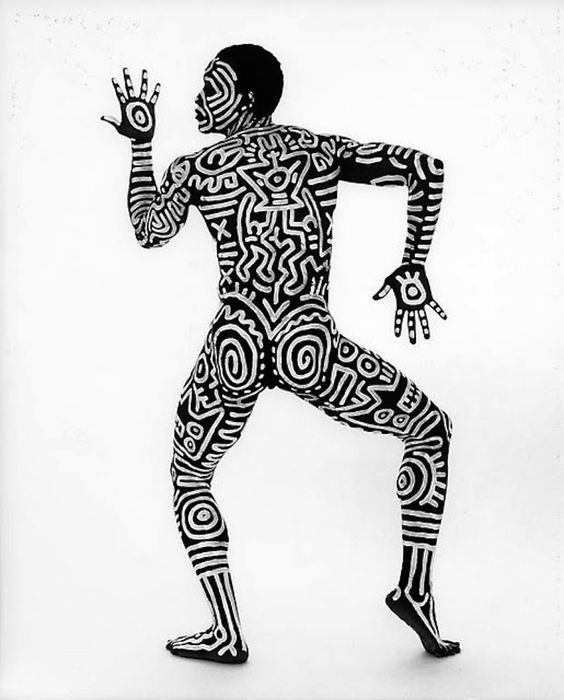

I’m being facetious, but as one of the architects of identity politics — I was in those Mapplethorpe photographs, I was talking about being an proud gay black man when so few of those voice were being heard. Now, I look over my shoulder and think we should have been more balanced ….

48 HILLS This really surprises me. There’s so many gay leaders and others telling us right now that we should “drop the identity politics” — for me that’s almost shocking to me, and yet it seems that you may be having questions yourself…

JONES The only thing I will say is that I thought I was doing the business of art. And art, in my way of thinking, going back to James Joyce and the early 20th century, was about trying to understand the nature of self, the nature of the indiviual in the great and crushing pageant of history. I was trying to understand, what did Martin Luther King mean by ‘free at last, free at last.’ What was freedom? Freedom to be who you are. Freedom to see the world, to see aesthetics, to see politics through the glasses of my choosing, so we had to define what that was.

I don’t think we have anything to apologize for in that regard. I think going forward, right now, I’m an elder. What does it mean to be an older gay man? Is it enough to be constantly talking about my orgasms, or my battles with youth culture as an aging object of desire? I have to find a way to really talk about the business of living. I have to vote. I have to have a political opinion.

So I don’t dodge away from my identity. But I do think I have to grow up and mature to be a full-fledged member of the culture. That is a bigger discussion. It does hurt me sometimes when some young people don’t know what we fought for or that they don’t know what it took to be able to say now that they don’t identify as a man or a woman. They have this raging sense that you could say who you were. Well. Some of us went before you, and many of us had to die to get you to that point.

We’re talking about the gay culture, but there’s much paralleling with civil rights struggles. When young black people say that there’s a kind of ossified sense of black identity and we’ve moved past that – well wait, slow down, what do you mean ‘move past that?’ Are you sure that everybody’s right and secure? Are you sure that it doesn’t matter anymore what color you are? Well you can see that that’s obviously not the case.

So I want to be humble, but I want to be fierce. And one way to be fierce is to stand up for what you love. I happen to love beauty. i love the world if ideas. I love a fierce man, woman, transgender person who is able to tell me something that I don’t know. Don’t keep repeating the same things. Get some new information. Learn something.

Maya Angelou used to say that everyone, whether you’re Irish, a Jew, a Muslim — this is America, you’ve been paid for. So go on, she said. You’ve been paid for. Echoing James Baldwin’s The Price of the Ticket. So we owe it to ourselves to be political. And to be as beautiful as we can be as creative animals. I’m sorry I’m on my soapbox here, but you opened that door. Go out there and make your beauty.

BILL T. JONES

A talk at the Arts & Ideas series

Sun/22, 7pm, $28-$38

JCC, SF.

Tickets and more info here.