SCREEN GRABS Comedy is seldom universal, and Italian comedy is as culturally specific as any strain of humor. Yet for a while, Italian screen comedies were widely exported, if only because for a while there Italy as a whole was a kind of global phenomenon. Slow to generally recuperate from WW2 like other erstwhile Axis powers (and many Allied ones, for that matter), Italy nonetheless was first out of the gate after the war in terms of stoking a new popularity for foreign “art” cinema.

There was nothing funny about its initial wave of neo-realist dramas, which influentially blurred the line between fiction and documentary to chronicle hard-hitting social issues. But by 1950 that genre had begun to lighten up a bit (that year’s big hit Bitter Rice offered at least as much cheesecake and lurid melodrama as gritty realism), and the unanticipated boom in Italian film production helped make Rome Europe’s most glamorous hotspot a decade before “Swinging London” would wrestle away that crown. In 1960 the city’s mix of sophistication, decadence, and history—not to mention its internationalism, complete with an invasion of Hollywood co-productions—was established enough to warrant the critical rapture that greeted Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, which of course only heightened the allure. Rome’s native daughter Sophia Loren was as big a sex symbol as Marilyn Monroe, with whom she had something else in common: Both were most at home in comedy.

The widespread popularity of Loren’s comedies co-starring Fellini muse Marcello Mastroianni, directed by neo-realist pioneer Vittorio De Sica, were just the tip of a genre iceberg. At its oceanic bottom were a vast number of cheap, cheerful ‘n cheesy enterprises starring strictly-local comedians that were never intended—or likely—to play outside the country. But between were a number of variably incisive, saucy comedies satirizing contemporary mores—or rather, the perilous gap between “traditional” morality and brash new freedoms, in a Catholic country that sometimes seemed to be shedding its inhibitions faster than a priest sheds robes in a sauna. There were several prominent talents of the era particularly noted as social satirists, none more so than Dino Risi.

The Milanese writer-director, who spent well over six decades working in the medium before he died at age 91 ten years ago, is being honored by a one-day retrospective at the Castro this coming Sat/22. Comprising four feature films and a “Commedia all’Italiana Party” (at which pasta will duly be served), this “homage to the master of Comedy Italian Style” is being presented by Instituto Luce Cinecitta as well as San Francisco organizations the Italian Cultural Institute and Cinema Italia SF. (It follows prior years’ single-day tributes to De Sica, Anna Magnani, Bernardo Bertolucci, and Pier Paolo Pasolini.)

Risi’s forte was using humor to examine the drastic changes that postwar life brought to Italian life. Though not everyone benefitted from the “economic miracle,” and various forms of institutionalized corruption remained intact, “Il Boom” raised many into a comfortable middle class that had hitherto barely existed. Such newfound prosperity, combined with larger liberalizing trends that crossed national borders, created a giddy schizophrenia: A culture long ruled largely by dedication to family, church and class distinctions pretended to still honor those institutions, while increasingly running headlong towards the nearest available materialism, mammon, and mammaries.

All four features playing the Castro approach that theme with both boisterous comedy and serious, sometimes savage social criticism. Risi’s favorite character—one with infinite variations—was the classic Italian archetype of the puffed-up, skirt-chasing male whose hubris knows no bounds even if the reality of his circumstances are considerably humbler than he lets on.

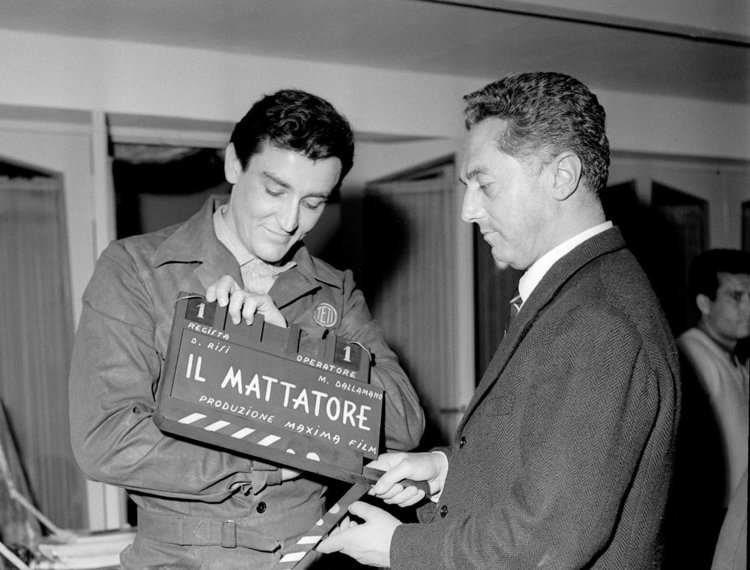

One of the writer-director’s first such major exercises was 1960’s Il Mattatore aka Love and Larceny, an ingenious construct told in flashbacks that relate the fabulous career of con man Gerardo (Vittorio Gassman). Now sedately settled in domestic life with his wife (Dorian Gray), he spent years pulling elaborate hustles that are portrayed in fetching detail here (one wonders how many real-life imitators they inspired). They allow the handsome star, a classically trained stage actor who’d started out in movies as a conventional leading man, to show off his chameleonic side in an array of persuasive disguises. Notably, Gerardo’s ripoffs succeed because he preys upon the greed, snobbery, and vanity of “respectable” fellow citizens.

Two years later actor and director teamed up again for the more cruelly seriocomic Il Sorpasso aka The Easy Life. Here, Gassman’s larger-than-life Bruno is a man of big appetites whose willingness to grab whatever he wants runs a gamut between bold exuberance and pushy obnoxiousness. He arm-twists contrastingly shy, modest law student Roberto (French star Jean-Louis Trintignant) into a weekend country joyride that’s ostensibly meant to expand the younger man’s horizons—but instead winds up underlining how Bruno is everything Roberto doesn’t want to be, a monster of selfishness and superficiality. As much as the more celebrated concurrent works of Antonioni and Fellini, Risi here was examining the modern Italian soul, and finding it bankrupt.

More breezily farcical if equally barbed was the next year’s I Mostri aka The Monsters, which in its often drastically-cut foreign versions was variously known as 15 From Rome and Opiate ’67. It’s a prime example of the “omnibus” feature, a form that was very popular (particularly in Italy) during the ’50s and ’60s but has become a rare beast since. The full original version being shown at the Castro is comprised of no less than twenty vignettes—some quite elaborate, others little more than a one-liner—satirizing various forms of moral hypocrisy in contemporary Italian society, from political and religious spheres to the marriage bed. If nothing else, it’s a dazzling showcase for the versatility of Gassman and Ugo Tognazzi, who each appear in nearly every sketch.

The ’60s marked a creative peak for Italian cinema in general, and the prolific Risi as well. Though he remained a busy and popular talent for several decades afterward (slowing down a bit only after he reached age 75 in the early 1990s), his later films are not as highly regarded, and await re-assessment. The only one included on the Castro program hasn’t aged so well, though it remains famous—if only because Al Pacino won an Oscar for chewing the scenery in its American remake eighteen years later.

The original 1974 Scent of a Woman aka Profumo di Donna is a more sentimental variation on Il Sorpasso’s mentoring dynamic, with Gassman as a blinded military officer who teaches a naive young soldier (Alessandro Momo) about Life and Love etc. during a weekend trip. Captain Fausto is a flamboyant embodiment of macho Italian horn-dogging, literally sniffing after the women he can no longer see, yet stuffed with enough ostensibly noble self-pity that he rejects the true love of an adoring girl half his age (Agostina Belli) because he is no longer a “complete” man. This conceit still works for many, although others may be put off by the leering pathos of a cad playing the world’s smallest violin for himself.

Once again, however, Gassman disappears into his role with complete commitment—this partnership with Risi was one of the great long-term actor/director collaborations. It’s a credit to Risi that during his long career he also frequently brought out the best in a wide range of primarily Italian stars, including the aforementioned Tognazzi, Loren, and De Sica (who maintained a prominent acting career throughout his directorial one), as well as Nino Manfredi, Sylvia Koscina, Alberto Sordi, Renato Salvatore, Elsa Martinelli, Marcello Mastroianni, Laura Antonelli, Giancarlo Giannini, Monica Vitti, and Ornella Muti.

“Dino Risi” plays Sat/22 starting 1 pm, Castro Theatre, SF, $12 (per film)-$60 (all day incl. party). www.cinemaitaliasf.com