ART LOOKS If you were a hip gay American man at a certain point in history, say about 1988-1993, you were expected to be in possession of a very specific set of items.

A worn jean vest heavily plastered with protest buttons. A thrift shop bust of Nefertiti. Campy sets of salt and pepper shakers. A record collection combining Patsy Cline, Patti Smith, Prince, De La Soul, an unintentionally perverse vintage children’s gospel album, and the latest from the undergrounds of Detroit, Manchester, and Olympia, Washington. Third-generation VHS copies of the three Johns: Cassavetes, Carpenter, and Waters. A small clown painting from John Wayne Gacy. A quilted cap or clunky piece of jewelry nodding toward the Afrocentric movement. Something Bakelite.

And on your rundown, downtown apartment walls? Well those were the windows of your connoisseurial soul. Posters of Dutch typography, Swiss design, Russian Constructivism, Maoist propaganda, French Nouvelle Vague … And photographs, mostly torn from coffee-table books or foreign magazines, by Pierre et Gilles, Joel-Peter Witkin, Nan Goldin, David LaChapelle, Diane Arbus.

And the great Peter Hujar, of course—a major part of whose oeuvre is featured in an absorbing, must-see retrospective at Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archives entitled Peter Hujar: Speed of Life (through November 18).

The show has been up since June. But it’s taken me this long to write about it, I think, precisely because his work recalls such a specific time in my homosexual life—I feel woozy before the task. Hujar’s indelible portraits of famous avant-garde artists and drag queens, and his curiously gothic landscapes and animal pictures, are so fastidiously exquisite, so fussily exact, so representative of a period past (“Speed of Life” is a very odd title) that they immediately summon the ratty hauteur, the necessary obsessions, and the cold-eyed dignity that helped most gay men survive, and not survive, in the early gay lib and AIDS years.

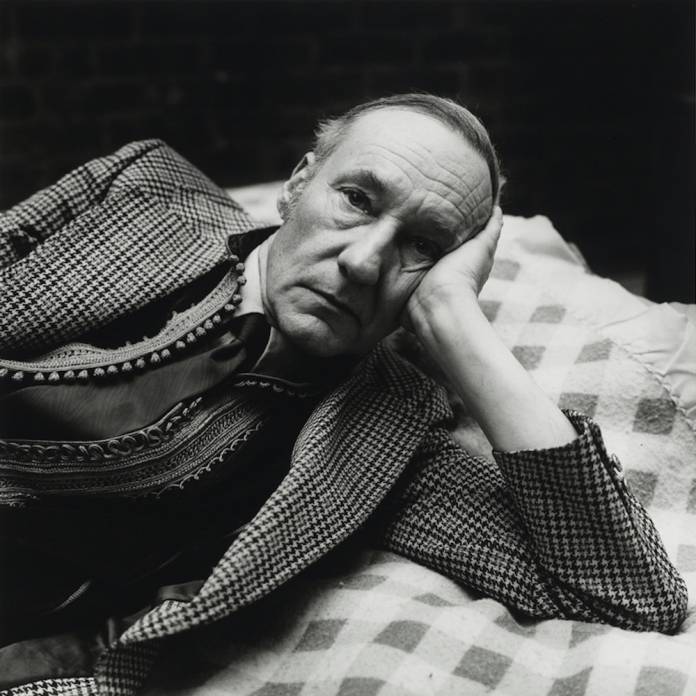

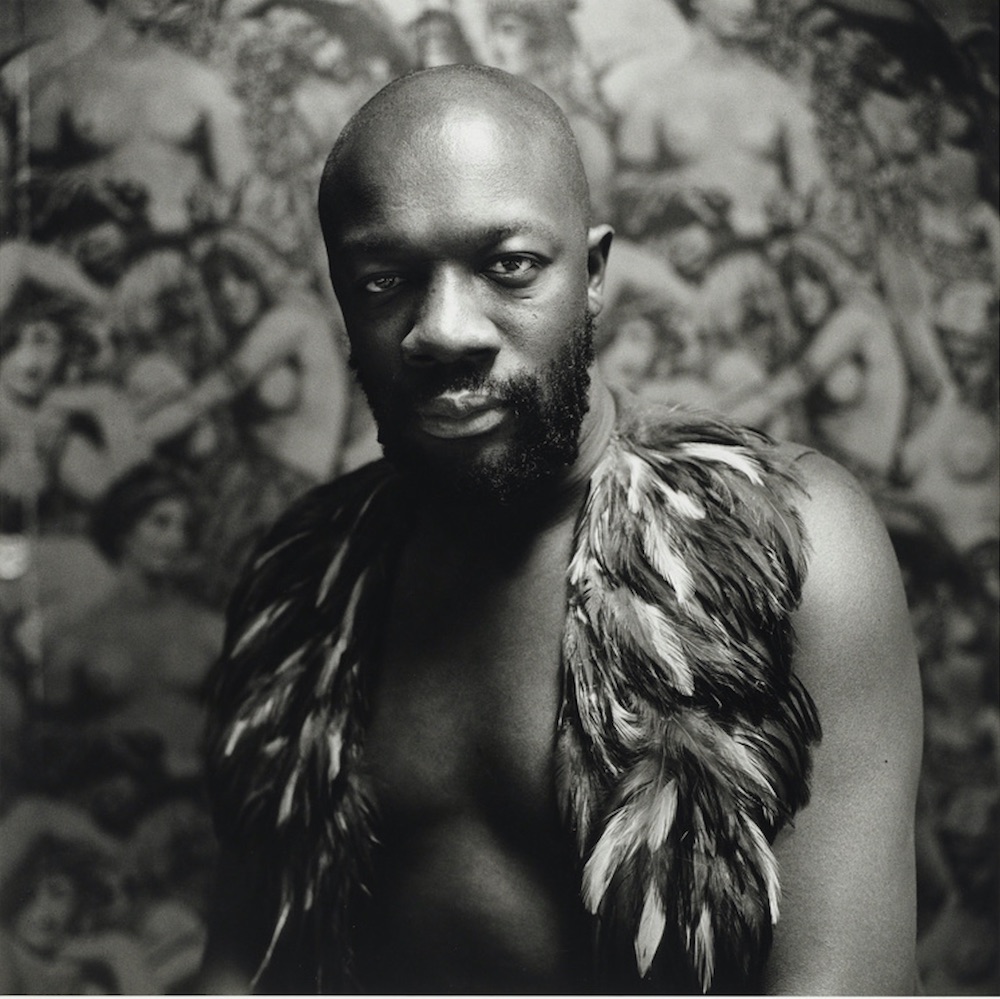

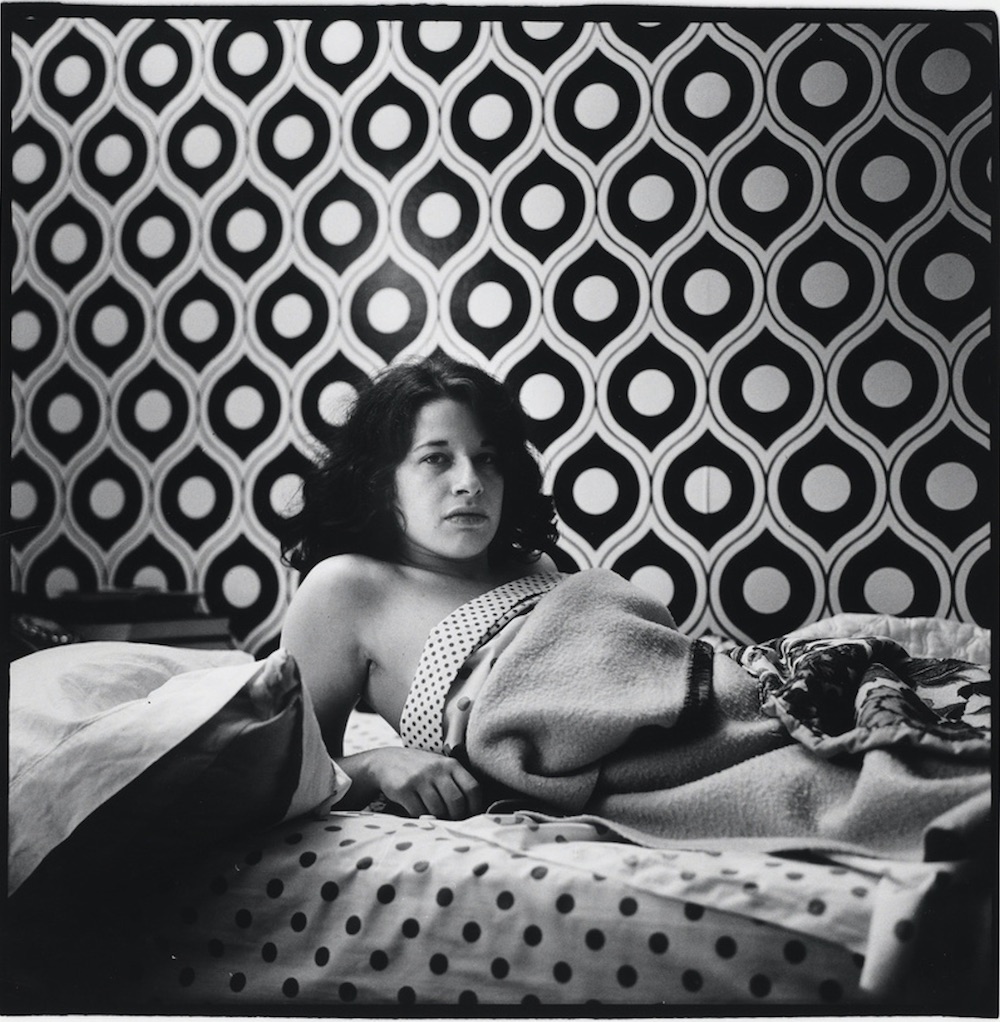

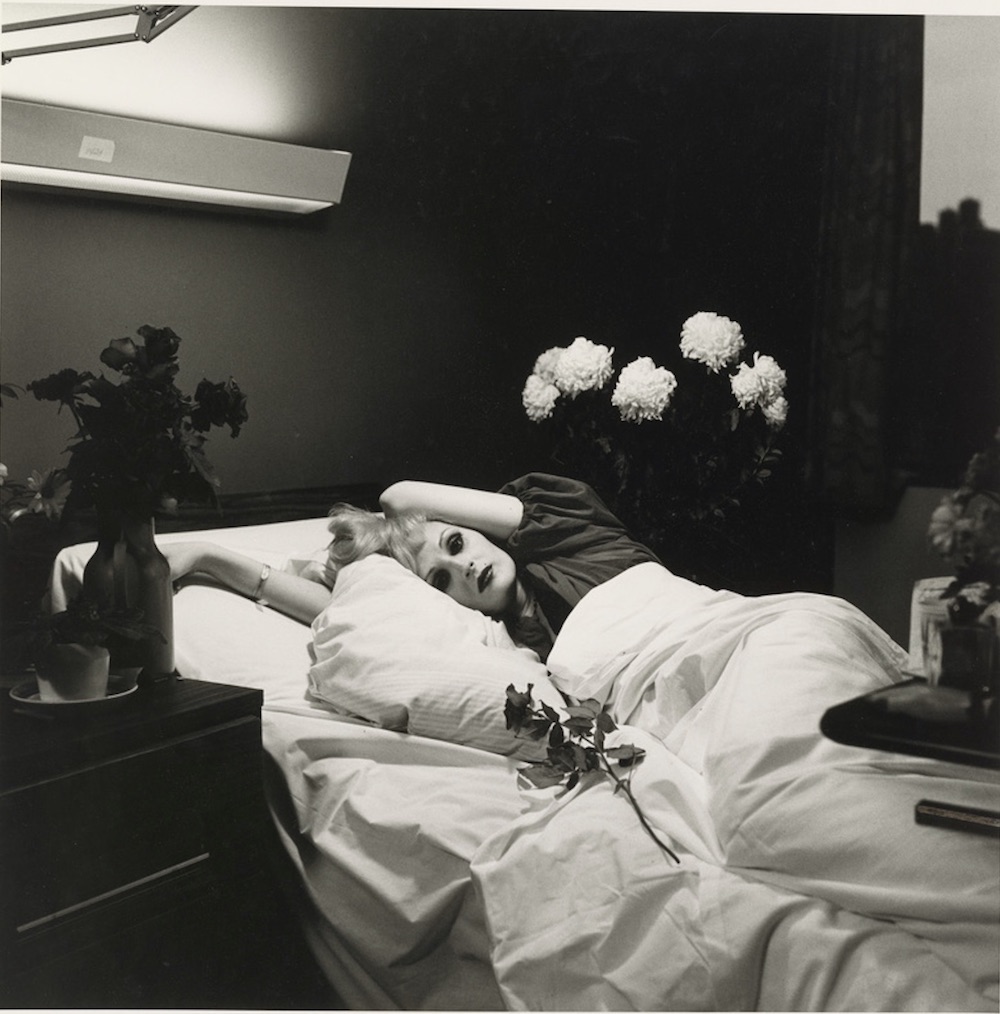

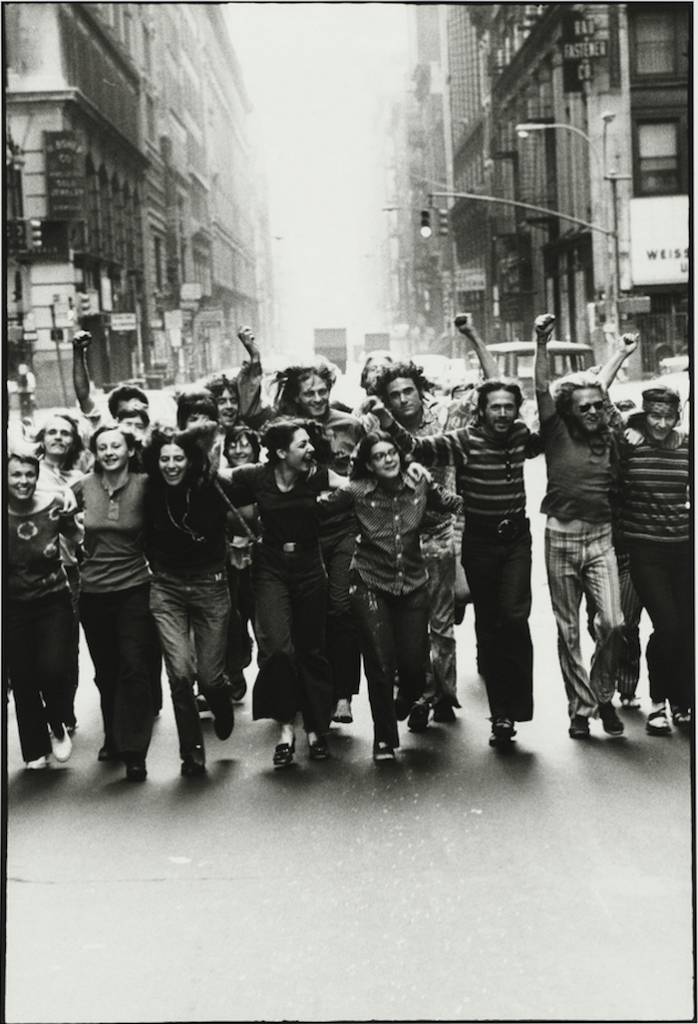

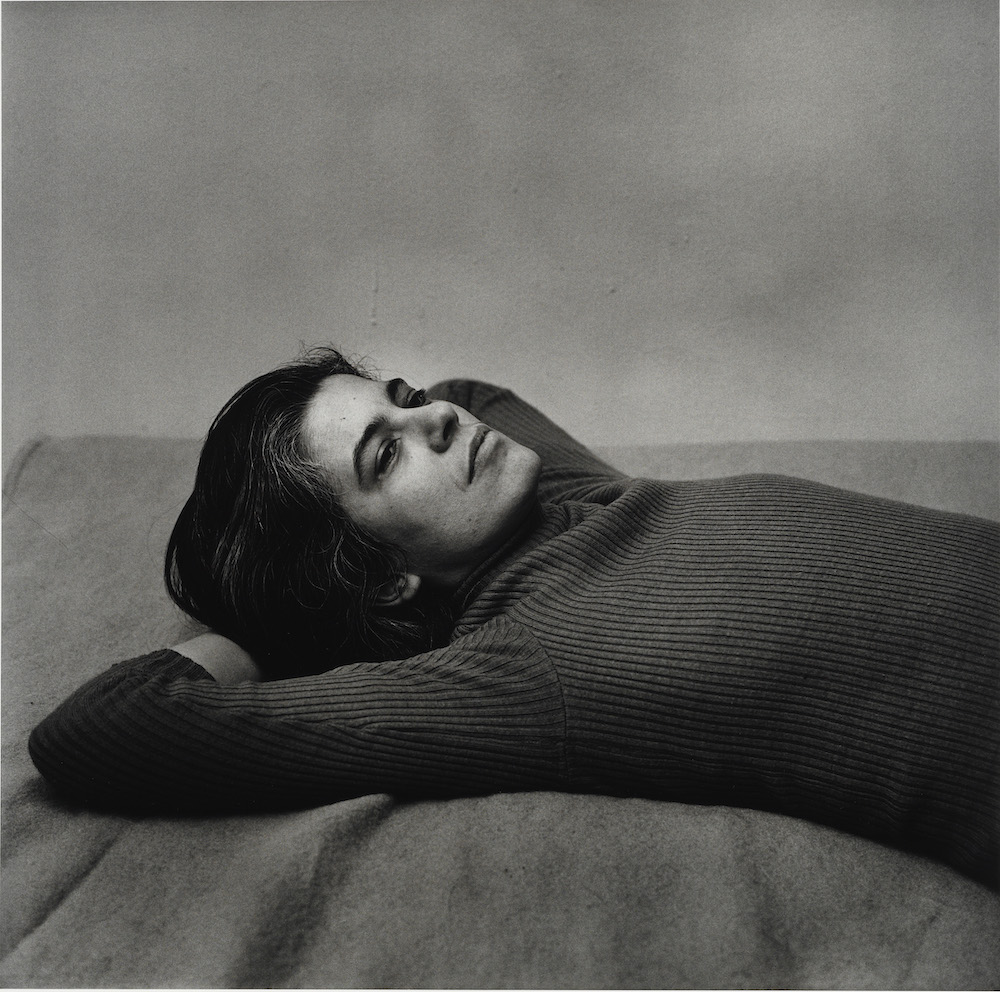

Hujar, born in New Jersey in 1934, was active in New York at its artsy 1970s-’80s peak, and “Speed of Life” is bursting with well-known pictures that continue to dazzle in their black-and-white perfection: Susan Sontag thrown back on a blanket, caught in a turtlenecked reverie; Candy Darling gazing softly from her flower-strewn deathbed; Cookie Mueller about to quietly read you from top to bottom and back. He achieved the twin miracles of making Fran Lebowitz look ravishing and William Burroughs look sympathetic. There are instantly recognizable photos of gay liberation moments which have been copied in famous TV shows and movies, and iconic snaps of gay men cruising the notorious piers.

He loved taking photos of people sprawled on beds or chairs—it was a way of disarming his subjects as well as creating his unique spatial compositions, which focused attention along the diagonals of a raised arm, say, or an asymmetrical hairstyle. “I make uncomplicated, direct photographs of complicated, difficult subjects,” Hujar wrote. “I photograph those who push themselves to any extreme, and people who cling to the freedom to be themselves.” That might indicate we’re in Mapplethorpe territory—and some of Hujar’s more erotic work, only some of which is represented here, does approach the lurid gloss of that leather-trousered master.

But Hujar is pulled in a more Victorian direction: His portraits often combine the freakish curiosity of Arbus and the monumental candidness of his mentor Richard Avedon into something resembling momento mori portraits suitable for displaying atop a casket. They are unmistakably contemporary but they feel historic, as if burned to silver plates. (Not for nothing did Hujar make his own display prints.) That doesn’t mean there’s no life in those portraits; far from it, these are the essences of his subjects so well-distilled that there’s really no need to go on. We see nostalgia washing over the present.

That’s OK—for every portrait of Divine looking outrageous at Studio 54, there should be an equal and opposite portrait of Divine slung against a mattress, looking like she’s wistfully solving a complex algebra problem. And the effect reaches a hilarious apex in Hujar’s pictures of animals, which never fail to look like local royalty—perhaps after the estate money has been exhausted. Two grazing cows face the camera like dowager duchesses out for a stroll, while a stout horse could be Prussian baron put out to pasture. Even Hujar’s cityscapes, brimming with Manhattan’s then-abandoned warehouse spaces and fantastical graffiti, seem not so much snapshots taken on the fly as he ran through the streets with his fellow artist and partner in crime, David Wojnarowicz, but etchings of some fallen empire from long ago. You’d hardly know Keith Haring and SAMO were gleefully bombing subway tunnels nearby.

Like Hujar, Wojnarowicz was an artist totally of his time—although while Hujar was reportedly cold and exacting, Wojnarowicz burned hot with political anger. (Coincidentally Wojnarowicz’s incendiary art was the subject of a huge retrospective called “History Keeps Me Awake at Night” at NYC’s Whitney this summer.) Both were very sexually liberated and passionate, but neither seemed the life of the party—despite finding themselves at the center of one of the 20th century’s most vital party scenes. In fact, Wojnarowicz’s incredible photo of Hujar right when he died of AIDS in 1987, aged 53, was the photo most of my edgier gay friends hung on their walls. Perhaps the death of the party is a better way to describe the pair in those upside-down times, and they were more celebrated for it.

That doesn’t mean there was a lack of charm. Two of my favorite Hujars are here: Blanket in the famous chair (1983) which shows a blanket his subjects sometimes used to keep warm bunched up and perched like an expectant ghost, and Daniel Schook sucking toe (1981), capturing an innocent-looking scamp with a bowl-cut holding his own toe in his mouth. It’s both obscene and uproarious, a Hujar rarity. (There’s a bit in the show about Hujar as an example of camp, but I fail to see it.)

“Speed of Life,” which traveled here from NYC’s Morgan Library, mimics Hujar’s preferred hanging. He wanted images displayed together, but no two similar ones near each other. Thus we get varied sequences of portrait, landscape, cityscape, animal, etc. Strangely, the overall result isn’t diversity, but similarity—he went for pretty much one perfect effect over and over, and he mostly achieved it. That effect powerfully pulls you back into a overwhelming moment of history, while revealing its personalities and complexities. It never feels stale or old-fashioned. But the timelessness sometimes leaves you wishing for a little air.

PETER HUJAR: SPEED OF LIFE

Through November 18

BAMPFA, Berkeley

More info here.

CURATOR JOEL SMITH ON PETER HUJAR

Sat/27, 1:30pm

BAMPFA, Berkeley

More info here.