ONSTAGE Ten years after Oedipus El Rey premiered at the Magic Theatre, Luis Alfaro’s drama is being staged there as a legacy revival, again directed by artistic director Loretta Greco. (Through June 23)

In the past decade, the play has been seen in 22 productions all over the country, ranging from Cal State Dominguez Hills to the Public Theater in New York. “Each production teaches you something about how to tell a story…you become a better storyteller with every production,” Alfaro explained in a program interview with Magic dramaturge Sonia Fernandez.

Of course, the story of Oedipus Rex has been told for more than two millennia, but Alfaro has transposed Sophocles’ drama to contemporary Latinx culture: to be specific, the Pico-Union section of Los Angeles, Highway 99 in Kern County, and the California State Prison in Delano.

The Greek chorus becomes the “Coro,” initially a quartet of inmates in orange jumpsuits, who also play barrio healers, an oracle of owls, street vendors and many other roles.

We first meet Oedipus (Esteban Carmona) in prison, where he is toughening up his body with squats, push-ups, and gut punches so he’ll be ready to take on the world when he is released. An older blind prisoner enters. It is Tiresias (Sean San Jose), whom Oedipus welcomes as his father. He has intentionally gotten himself sentenced to prison so he can look after his son.

In a flashback, we learn that the baby Oedipus was taken from his mother Jocasta (Lorraine Velez) at birth. His brutal father Laius (Gendell Hing-Hernandez), having been told by an oracle that the gods have determined that his son is destined kill him, orders the child murdered. After Laius slashes the baby’s feet, Tiresias agrees to take him away.

When Oedipus gets out of prison, he races down Highway 99 to Los Angeles—even though Tiresias has warned him that danger lurks there. In his haste and hubris, Oedipus gets in a fight with an irate driver and ends up killing him. He does not realize that the victim of his road rage is his real father Laius.

On his arrival in the city, he is greeted by vendors selling everything from paletas and tamales to laminated Social Security cards, and when he meets up with his former prison buddy Creon (Armando Rodriguez) he learns there is a lot more for sale in the underground economy, from drugs to stolen cars parts.

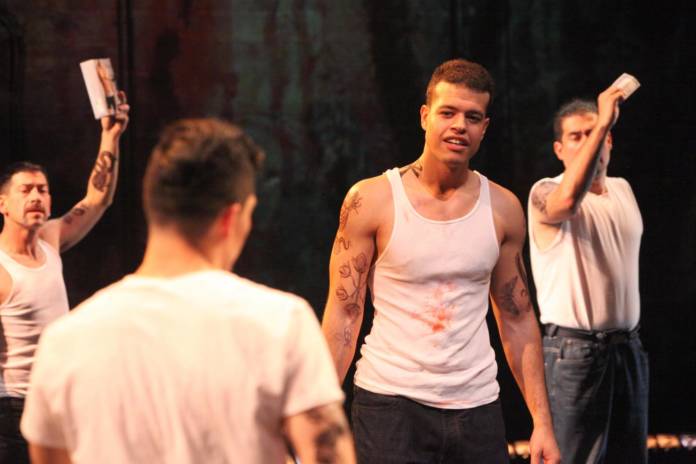

The set design by Hana Kim is stark and unadorned—and effective. By using only bare walls, a concrete floor, and light projections, her design emphasizes that this story is a universal one. In fact, there is more decoration on the actors’ skin than on the walls, and credit is given to Jacquelyn Scott for tattoo art design and execution.

There are moments when the action sparkles against this bare-bones backdrop. The wedding of Jocasta and Oedipus, complete with upbeat music and crowds of dancers (most pulled from the audience), is tense with the newlyweds’ evident joy and the foreshadowing of their tragic fate. Greco’s staging of the boisterous party juxtaposed with silence during the vows underscores the ominous nature of the scene.

Under Greco’s direction, the cast strikes that delicate balance between the heightened emotions of Greek tragedy and the visceral rendition of life in the tough and gritty present.

Velez beautifully portrays Jocasta’s agony in childbirth, sorrow at losing her child, and her tenderness as she reawakens to love. San Jose’s wise Tiresias and Hing-Hernandez as the cruel Laius are magnetic. The exhortations of the curanderos—el sobador who uses touch, el huesero who realigns bones, el curandero who cures spiritual illness and el mistico—are both humorous and compelling.

Unfortunately, Carmona’s Oedipus never seems to find that crucial balance as he bounces between an arrogant, self-assured wannabe king and an innocent youth overwhelmed by the choices of life outside prison walls.

Alfaro, an incredibly talented and widely recognized playwright, is a recipient of numerous theater awards and a MacArthur “genius” grant. When he first staged this play, California was at the height of its prison boom: 43 new prisons had been built in a decade, and the state had the highest number of prisoners in the country, 2/3 of whom were Latinx or African American, 60% from Los Angeles.

Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness came out the same year that Oedipus El Rey premiered. Latinx and African American people were well aware that their communities were being decimated by a racist criminal justice system, but the policy of mass incarceration—as intentional as Jim Crow laws—was not yet part of the popular political discourse.

When it premiered, Oedipus el Rey—like The New Jim Crow—was a breakthrough, jolting audiences into seeing the parallel between the fate of Oedipus sealed by the gods and the fate of a young Latino foster child at the hands of today’s power holders. Alfaro’s Coro asks “Will no man be feliz, until he’s six feet under?” then a prison door slams shut. Perhaps we will have to wait for Alfaro’s next adaptation to learn the answer to that question.

OEDIPUS EL REY

Through June 23

Magic Theater, SF.

Tickets and more info here.