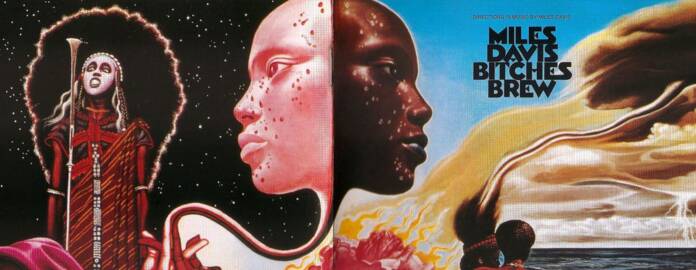

Miles Davis entered Columbia Records Studio B in Manhattan on Tuesday, August 19, 1969—one day after the Woodstock Music festival ended. There, his explorations with electronic, funk-rock, and experimental jazz compositions, using electric piano, guitar, congas, and shakers, made his trumpet playing fidgety-aggressive, anything but cool. “Call It Anything” was one of the working titles used for the project, his genre-smashing double album Bitches Brew.

While the country pushed The Rolling Stones’ “Honky Tonk Women” to the number one spot on Billboard, during three recording sessions that took place for three days-from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. (less time than it takes a letter to get from the East Coast to the West Coast in our bizzaro year of 2020) Miles Davis bum rushed a culture change in jazz. Released March 30, 1970, on Columbia Records, Bitches Brew has since sold over a million copies, a landmark feat for a jazz record. The release reacquainted the mainstream with the genre, and changed the course of popular music forever.

Davis was obsessed with James Brown, Sly Stone, Jimi Hendrix, popular artists of the day who hypnotized young music fans with tight but loose rhythmic structures, devoid of melodic components. He bolstered his rhythm section in the style of Fela Kuti, picking up Kuti’s practice of vamping, or repeating a chord progression or groove. Producer Teo Macero, picking up on the idea, used his tape cutting in the edits—doing his own labor-intensive version of hip-hop.

Understand, Davis wasn’t planning on creating new business models for labels named Brainfeeder, International Anthem, Alpha Pup, First Word Records, Brownswood Recordings, Black Focus Records, 2000Black, and a plethora of contemporary imprints. But nonetheless, these jazz-electronic music-fluid hybrid seedlings were born out of the evolution he created. That yearning for connection with young Black culture in the late ’60s—less Motown and more Funkadelic—positioned Davis forever in the future.

Miles married Betty Mabry, a 23-year old model and songwriter in September of 1968. She changed his hair, clothes, fashion, and listening habits. In his autobiography he called her a high-class groupie, but despite this seeming disrespect, it’s clear that he listened to her insights. Mabry was a frequenter of Greenwich Village and made introductions for him in that landscape. Soul, rock, and funk became his focus. Jimi Hendrix, who Davis accused Mabry of having an affair with, triggering their divorce in 1969, crystallized the essence of this new Village-born sound. But Miles knew he could play better than these young dudes. (Betty Davis took umbrage at his well documented schizophrenic condition with her singular account He Was A Big Freak.)

With Miles having assembled the greatest jazz players in the world, his Bitches Brew sessions were packed with hungry young virtuosos. All those egos would have driven any other bandleader batshit cray. But not Miles. This was Michael Jordan + Muhammad Ali + James Brown + some parts Kobe Bryant; the ultimate Black alpha male, who ate suckers and mf’ers like candy bars. Not only a musical icon, a leader of men. He could sit at the bar, listen to his band, hear something askew, go on stage, and play one note, ONE LOUD NOTE, for an extended period of time. Changing the music around him on a dime, taking the arrangement to another place.

Nobody was fucking with Miles in the studio. Nobody.

That legacy was extended by the extraordinary musicians he summoned, who would carry his fusion flag for the next decade. Davis’ understanding of human chemistry extracted potential from them even they didn’t know they had. On Bitches Brew, a great deal of the music came from arrangements scrawled on scraps of paper, products of an improvisational process, “not some prearranged shit” according to his autobiography.

Help us save local journalism!

Every tax-deductible donation helps us grow to cover the issues that mean the most to our community. Become a 48 Hills Hero and support the only daily progressive news source in the Bay Area.

Drummer Lenny White reflected on those sessions:

“During the session we’d start a groove, and we’d play and then Miles would point to John McLaughlin and John would play for a while, and then Miles would stop the band. Then we’d start up again and he’d point to the keyboards, and someone would do another solo. All tracks were done in segments like that, with only the piano players possibly having a few written sketches in front of them […] Bitches Brew was like a big pot and Miles was the sorcerer. He was hanging over it, saying, ‘I’m going to add a dash of Jack DeJohnette, and a little bit of John McLaughlin, and then I’m going to add a pinch of Lenny White. And here’s a teaspoonful of Bennie Maupin playing the bass clarinet.’ He made that work. He got the people together who he thought would make an interesting combination […] It was a big, controlled experiment, and Miles had a vision that came true.”

It’s not just Miles that makes the record so special, it’s the people behind him, the collective whole.

Joe Zawinul on the left electric piano, Chick Corea on the right electric piano, and Larry Young—a former Jimi Hendrix collaborator—as the third electric pianist. John McLaughlin (who Jeff Beck and Pat Methany, rock fusion luminaries, call the best jazz guitarist alive) on electric guitar, Dave Holland on bass, Harvey Brooks on electric bass—possibly a fill-in for Ron Carter who refused to switch to the instrument for the sessions-started out playing with Bob Dylan and The Doors. Bennie Maupin on bass clarinet (Maupin would later play in Headhunters and Meat Beat Manifesto) and Wayne Shorter, winner of 11 Grammys, on soprano sax. Lenny White, at the age of 19, served on the left drum set, playing alongside the veteran Jack DeJohnette, who in turn had played with John Coltrane and many others.

That was your core ensemble. Three pianos, two basses, two drummers, one soprano sax, one bass clarinet, and Miles Davis on trumpet. That’s an arsenal. Plus Billy Cobham, Airto Moreira, Don Alias, and Juma Santos, who filled out percussion duties on “Feio” and “Miles Runs The Voodoo Down.”

Who in their right mind would want to go back to playing dusty jazz clubs to an outdated audience, sipping on their watered-down two-drink minimum? Shit was old. Meanwhile rock and funk acts, led by mostly inferior musicians, were making three times what Davis was pulling in those clubs from one festival or stadium show. But what seemed safe to some artists felt like death by a thousand cuts to Davis. No risk, no growth.

And so you hear Davis yell through the trumpet “I’m alive” in that opening segment for the manifesto call on Bitches Brew. With incremental keyboard and bass crawl, immediately struck moods of chaos, Davis sets himself up for that Godzilla trumpet charge, alerting the city, reverb and delayed, carrying over everything.

It’s a pronouncement: Black Power is putting folks on notice. Bitches Brew calls out the Beatles and the Rolling Stones as the best bands to rip off Black music and become gods. While too many blues, R&B, and disco artists—not to mention contemporary Black DJs today—die young, broke, and without health insurance.

Some get it, others don’t.

Jazz critic, esteemed author, and historian Stanley Crouch, alongside documentary filmmaker Ken Burns, cast off this era of Miles. Rolling Stone honored Bitches Brew by putting Miles on its cover; the first jazz artist to ever get that treatment.

The commentary resides within the margins.

It’s only over the last 10 years that experimental beat scenes and weird pockets of club music have provided legitimate contrast, extending that idea of vamping into a business structure. As always, it’s the youth dragging old things into modernity. London and LA artists bring their generational perspective through a prism of electronics and experimentalism. Theon Cross, Nubya Garcia, Joe Armon Jones, Kamaal Williams, Kaidi Tatham from London. Then southern California artists Ryan Porter, Thundercat, Flying Lotus, Georgia Anne Muldrow, Daedalus, the late, great Ras G, and so many more pin drop where Miles’ off-chart tempo changes, rhythmic surges, infusion of world music influences … left off.