>>We need you! Become a 48hills member today so we can continue our incredible local news + culture coverage. Just $20 a month helps sustain us. Join us here.

Burning Man is dirty and getting dirtier.

Fine dust covers everything in the Black Rock Desert. During the annual late-August Burning Man gathering, it swirls in the air with carbon dioxide emissions comparable to Mexico City and other dense, dirty metropolises, thanks to burners’ heavy reliance on fossil-fueled generators.

The epic rainstorm that hit Black Rock City during last year’s event cleaned that dirty air even as it turned the ground to impassable mud. So a Burning Man that began with climate activists blockading the road to the playa to protest burners’ wasteful consumption ended with the lowest daily carbon emissions in years.

But that’s not where things were headed before the storm.

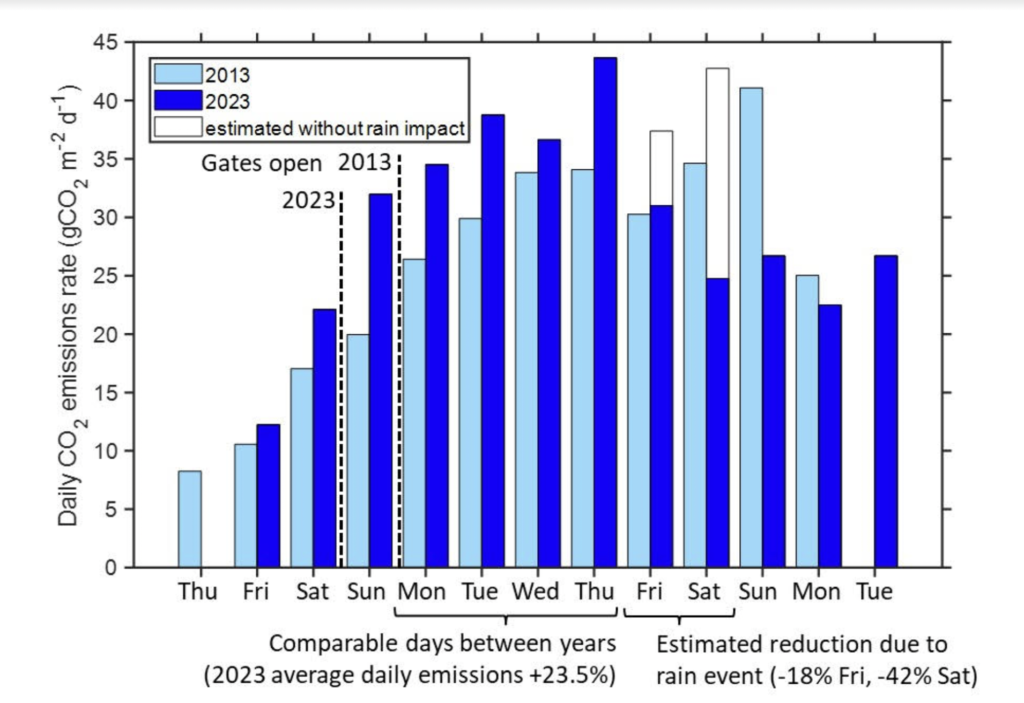

Daily carbon emissions were way up at Burning Man last year, according to new climate data collected by a team led by climatologist Andrew Oliphant, director of the School of the Environment at San Francisco State University, compared to data his team collected in 2013.

The analysis shows a precipitous drop in carbon emissions on the Friday afternoon when the rainstorm hit as everyone bunkered down and turned off their camp generators. But it dropped from a Thursday that had the highest emissions of any day in either year, even higher than the climactic burn nights (Saturday and Sunday) of 2013.

Overall, the data show a 16 percent increase in daily carbon emissions Monday through Thursday after controlling for the increased population. Even with the days last year when emissions were severely dampened by the rain and mud, overall carbon emissions were still up 11 percent from 2013.

Yet event organizers at the Burning Man Project continue to deny how carbon-intensive their party in the Nevada desert really is, making wild aspirational claims that Burning Man innovations are actually helping solve the global climate crisis rather than admitting to their own rising emissions.

When presented with the new data (as well as its own census data showing increasing reliance on dirty camp generators), the organization told me, “Burning Man Project aims to serve as a beacon of hope and inspiration around sustainable innovation through the ways we are expanding our solar and renewable capabilities, testing new technologies & incorporating them into our power grid, and working with participant camps and groups to get off fossil fuels.”

Maybe. But as with so much about Burning Man, its hopeful hype masks a dirtier reality.

Climate Tower

Our 100-foot-tall climate flux tower was an illuminated beacon visible from anywhere in Black Rock City. Andrew the climatologist is a good friend of minex. I helped show him around Burning Man during his first visit in 2013. So when he and his researchers decided to reprise that climate data experiment 10 years later, I joined them.

For the climate researcher, the real appeal of Black Rock City was its isolation and duration. Oliphant’s instruments could record the mid-sized city’s carbon emissions, heat exchanges, how pollution circulates at ground level, and other micrometeorological data as Black Rock City grew from the dust, peaked, and was broken down. There aren’t any major developments for many miles to contaminate the data, making it an ideal climate case study.

“It was the chance to measure the micrometeorological impacts of a city as it grew,” Oliphant said.

After presenting his 2013 data and the peer-reviewed publication of his research, Oliphant became a bit of a rock star in academic world of climate scientists. “I took it to the International Urban Climate Conference in 2015 and presented it to them and it was unexpectedly well-received,” said Oliphant, who won the award for best paper that year. “It was my 15 minutes of fame.”

His research helped scientists create better models for creating and analyzing refugee camps, forecasting weather patterns, and helping the insurance industry improve their models for predicting damage from hurricanes. Seeing how his colleagues received and used his data, he said, “It made me think I’d like to go back.”

But Burning Man Project leaders didn’t embrace the research, despite their loudly proclaimed interest in sustainability, reducing emissions, and addressing climate change, although Oliphant did present it to the organization on June 13 during a Zoom meeting.

In my repeated exchanges with Burning Man Project spokespeople and sustainability staff for this article over the last few weeks, they never copped to the rising emissions or their implications, instead emphasizing Burning Man’s expansion of renewable energy generation.

That includes increasing their solar panel capacity and using it to power much of its infrastructure, construction of the temple, and lighting of the Man. But that does little to address the main source of carbon pollution at Burning Man: reliance on generators by camps and individuals.

The Burning Man Census shows more than half of attendees rely on their camp generators for power, up from just over a third in 2013. Those generators ran for an average of 11.6 hours per day last year, down slightly from super-hot 2022, but up from 10.5 hours in 2016. This, and the dust, is why Black Rock City has such dirty air.

It is true that more people are using solar panels, with almost half of attendees reporting using them last year, up from 30 percent in 2013. But much of that is performative, with many big camps using a token amount of solar panels even they power their increasingly ambitious camps mostly with dirty generators.

Those realities were reflected in Oliphant’s data: Black Rock City’s population peaked at 78,000 last year, with its average daily population up about 6 percent from 2013. But the average daily emissions were up almost 24 percent from 10 years earlier.

What’s Going On?

As a scientist focused on data collection, Oliphant is reluctant to speculate about why Burning Man is getting dirtier, despite the organization’s efforts to green the event. But there are some obvious factors driving the increase.

One positive point Oliphant has often made about Burning Man is that while its per capita carbon dioxide emissions are very high, it differs significantly from other cities in that very few of those emissions come from the transportation sector (at least if you exclude the emissions-heavy periods when people arrive at and leave the playa).

During the event, everyone gets around on bicycles, art cars, and on foot, with private auto use banned. As a result, Andrew and his team concluded that carbon emissions for vehicles during the week was actually lower than human respiration. In other words, we exhale more CO2 than our vehicles emit.

But these days at Burning Man, many people zip around the playa on E-bikes, so that green transportation dynamic is changing.

“In 2013, there was a negligible number of E-bikes out there,” Oliphant said. “Our surveys from last year show about 20 percent of bikes were E-bikes, and they need charging.”

Another factor in the increased emissions is the increasing wealth of attendees. The census data show far more rich people coming to Burning Man in recent years and a declining population among those in the median income range. Tickets prices for Burning Man have also increased significantly, this year costing $725 plus fees for a ticket and vehicle pass.

“I told the organization that if you lower your ticket prices, you’ll get more lower income people and that will lower your emissions,” Oliphant said.

He pointed to my own experiences as an example. In 2013, when I was struggling financially, I carpooled with friends and camped in a tent. In 2023, I’m much better off, and my wife and I arrived and rode out the storm in the RV we now own.

Another change in the last 10 years is the increased availability and efficiency of solar power generation. Solar is a great ideal, but in practice it doesn’t always yield enough power to fuel our Burning Man project ambitions, even in a place with abundance sunshine.

“We learned that first-hand in our camp,” Oliphant said. “It was tough to generate enough electricity through solar to run the lights on our tower all night, so we had to use the generator if we wanted to keep them on.”

That’s right: the bright beacon of our massive carbon flux tower recorded the rising climate impacts of Black Rock City, while also serving as an example of how tough it is to shine in a climate-friendly way in the harsh environ of the Black Rock Desert.

Lessons from the Storm

We knew last year that the storm was coming on Friday, but we didn’t know it would stall out over Black Rock City and dump nearly an inch of rain over about 24 hours. The playa turned into a mucky mess, stranding more than 70,000 burners, a quasi-disaster that made national news.

After stocking our camp’s covered bar with drinks and ice to help our tent-dwelling campmates ride out the storm, my wife and I bunkered down in our RV to watch things unfold. As a veteran, I know to sit tight and wait it out.

From our windows, we watched bikes and vehicles stuck in the mud, unable to move, and even those on foot walked on mud-caked platform shoes, leaving messy clods in the wake.

Normally on Saturday night, most of the city would gather in the inner playa for the burning of the Man. In 2013, Andrew’s data showed how emissions would drop to very low levels on Saturday evenings as everyone gathered for the Man burn and shut down their camps, only to rise sharply after the burn as people returned to base and powered up their camps.

But last year, the rain and flooding kept everyone close to their camps on Saturday night and delayed the Man burn until Monday night (when Andrew’s data again showed an emissions dip during the Man burn).

When everyone would normally be gathered together to watch The Man burn and party hard into the night, we were instead staying in the camps on our block. In our case, that was the piano bar next door or AwesomeVille across the street, both of which had live bands and festive, happy crowds.

As someone who no longer enjoys the chaotic frenzy of Burn Night, this was one of my favorite Saturday nights ever at Burning Man. You can see that localized reality reflected in Andrew’s data, with Saturday’s emissions below even those of the previous Sunday, when the gates first opened and Black Rock City was just being built.

Andrew sees lessons in that data, and opportunities for the Burning Man Project if it ever wants to get serious about reducing its rising carbon emissions.

“One of the storm’s effects was to really lower the emissions. So what can we learn from that? I don’t know, but what if we had a stay-in-your-neighborhood day?” he said. “It was an activity-driven reduction in emissions. So what can you do to replicate that?”

Steven T. Jones is the author of The Tribes of Burning Man: How an Experimental City and the Desert is Shaping the New American Counterculture. He writes a weekly newsletter on Substack called Scribe’s End Notes, where a version of this story also appears.